I feel like I’m revisiting a subject that’s been widely debated elsewhere, but not finding what I’m looking for in various online articles, I’ve decided to quickly return to this question of sizing, estimation—quick and visual. During one of my interventions, at what the agile community now calls a “PI Planning,” I observe once again a frequently repeated pitfall: we spend more time quibbling over estimates than asking ourselves the real questions about what we need to build, than doing storytelling to better communicate and understand our needs.

Naturally, estimation and sizing are initially a useful pretext for a real conversation, but when the subject becomes 3 or 2, 0, 5 or 1—the estimate itself—we’ve missed something and wasted time. Ideally we should stop estimating altogether, and instead break down the elements we’re going to work on in the near future, and simply prioritize them. Small valued and prioritized elements are sufficient. Breaking things down is estimation in disguise. Without numbers. For the full validity of this approach, or rather the invalidity of estimates, I refer you to these consolidation slides here on the #noestimate and #beyondbudgeting movements.

An organization’s maturity on this subject often varies. And our advice, our suggestions, are only valid if they take this evolution, this temporality into account. I’m not often going to advise an organization to go directly from man/day to #noestimate. I’ll probably more often suggest they try without man/day, then without numbers, then with visual sizing phases that are faster than planning poker, and finally perhaps mention #noestimate. And I hope to be overtaken by the organization on these proposals, and just support them in implementation. There’s little definitive advice, there’s little agile that imposes itself, there’s a context, a temporality in our support, in our proposals.

Anyway, for this organization I need to clarify the practice of visual estimation (many know it by the term extreme quotation, from which I believe I’m changing a few details, but the devil’s in them…). Initially I discovered a first draft in an old article by Ken Power, on silent wall-based poker (which I just found here).

The essential idea to grasp is that we’re bad at estimation, and good at comparison. And therefore that there’s no point wasting too much time on something we’re not good at. Have as many conversations as necessary about your work thanks to estimates as long as estimates don’t become the subject of your conversations. Bad at estimation? Does it still need repeating? See Duarte Vasco’s references. More playfully, go watch this TED by Clio Cresswell on mathematics and sex. This TED is absolutely hilarious and fascinating, we learn whether your couple will last more than six years and plenty of other things but especially beyond the estimate itself that our counting strategy is often flawed. If you enumerate your partners (David, Dragos, Pablo, etc.)[1] you’re going to underestimate your estimate. If you give an approximation (“So 5 per year for the last 5 years,” etc.) you overestimate. Bad estimation, bad aggregation (and therefore probably a bad commitment, a bad projection). Might as well turn to something more effective and more reliable: comparison.

How to conduct a visual sizing session?

- You break down your needs, your activities, on pieces of paper (yes, like post-its).

- A global and/or precise presentation can be done (but the idea is to save time so rather get into details during a later step)

- You ask people not to talk initially. The idea is to talk, to converse as much as necessary afterwards on the 20% that require it and therefore save time on the other 80%.

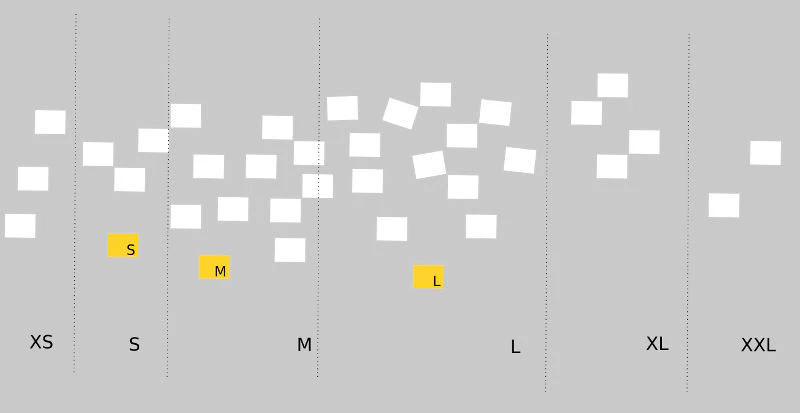

- In silence everyone takes a piece of paper / post-it describing a need, an activity, etc., and places it on the wall respecting the rule: the less effort it requires the more it should be placed on the left of the wall, the more effort it requires the more it should be placed on the right of the wall. Above all, no scale is placed on the wall, it’s really the physical distance that creates the analogy with the difference in effort. I insist on the fact that there be no number, no scale proposed in advance contrary to all the other ways of doing this that I’ve observed.

Effort? A combination of complexity (brain juice), toil (repetition of gesture, multiplicity of variations), and obscurity (we don’t have all the elements in hand). But effort ultimately remains time (completion time), which we will never detail: when time comes into play in numerical form all our calculations are even more erratic (because the reference becomes our calendar, the product’s calendar, something else, but no longer the activity to be completed).

- In silence the post-its / pieces of paper are stuck to the wall. They can be moved, by anyone. And re-moved. And re-re-moved. By anyone. By others. By oneself. This is how we identify the elements that will require a more thorough conversation.

- Have a more thorough conversation on the elements that require it (Pareto 80/20): those on which convergence hasn’t occurred, and / or those that are very far right if the estimated effort is due to a lack of information, too many uncertainties, and they’re priorities.

- Finally we look for previously completed activities (from the previous period, two or three representative ones) and we ask people to place them on the wall. Suddenly your scale appears (whether it’s numbers or something else), and then you go “with an axe” to show that an estimate cannot and should not be precise because by definition it’s an estimate, a hypothesis. It’s your attitude that conveys the message, that demystifies certain beliefs. You aggregate the post-its / pieces of paper around the scale that suddenly appears.

Conclusion

In this exercise everyone was able to visually compare elements: it’s about the same effort, it’s more, much more, less, much less, etc. The more elements we have the more substantial the comparison becomes. We’ve completely eliminated any scale other than the physical one (of the wall) and thus we’ve enormously reduced conversations about estimates to concentrate them on the stories, and only those that had no consensus or too many uncertainties. We apply a scale after the estimates are completed and this scale comes from an observed cadence, not from another estimate. We were fast: 80 elements in 20 minutes? But we’ve lost the conversations that are nevertheless essential: we can find them again at the end of the exercise for the 20% that require them. We can find them again later when it comes to really projecting ourselves onto the work to be done, just before committing to it. We can find them again as we go along. Everything depends, once again, on the context.

[1] These first names are not real. The real first names have been hidden.