Short follow-up to the kanban project portfolio part 1 from January 2016. Short, because the essentials of this introduction to kanban were present previously.

What are we measuring?

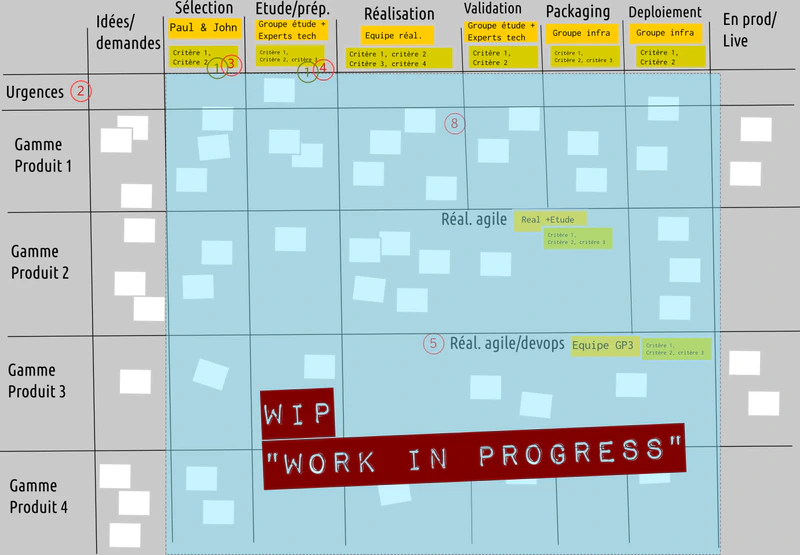

So ultimately what are we measuring? Well quite simply, for example, the number of elements in your kanban. Therefore the number of elements on which an effort of value creation is accomplished. It must be understood that the kanban shows a living flow, a work in progress. Apart from the first and last columns which are dumping grounds (important ones), all the other columns should show activity, action, dynamics. If you have several thousand anomalies and a kanban linked to managing these anomalies, you’re not going to place them on the wall, it’s impossible and useless. You’re going to let into the kanban flow those on which you want to work (that’s already a strong decision).

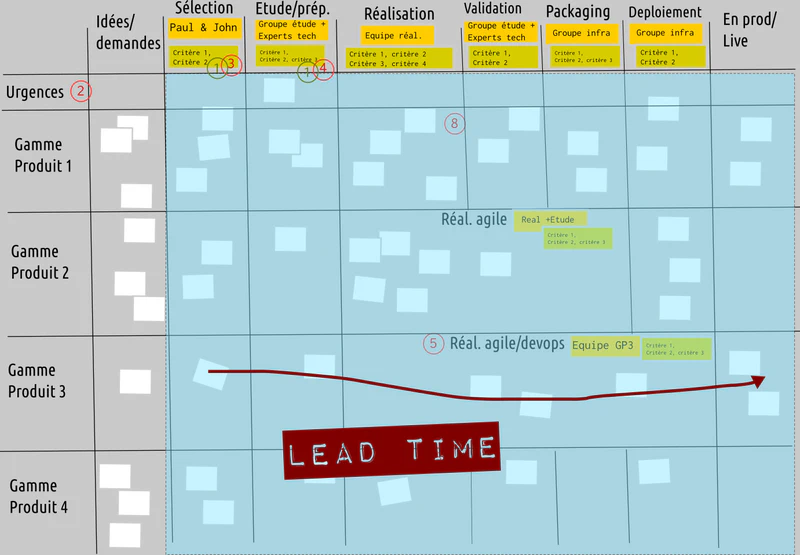

So you’re going to measure the number of elements in your kanban, and you’re going to measure the average time it takes for an element to cross through the stages. You thus have two key pieces of information: how many elements and in how much time. A cadence appears, it can and should help you govern, plan, make decisions. We generally call the “how many elements”: the wip (work in progress), and the “how much time”: the lead time (or cycle time, there are variations in the definitions), the lead time is the time from when the card enters the kanban until it arrives at finished (or for cycle time, the time from the start of the work until the end of it, or according to other definitions, the time between certain columns of the kanban).

Yes there are probably different elements in the kanban, which don’t compare to each other. Do your best. Sometimes it’s useful to distinguish them, sometimes not, but you’ll know how to answer that.

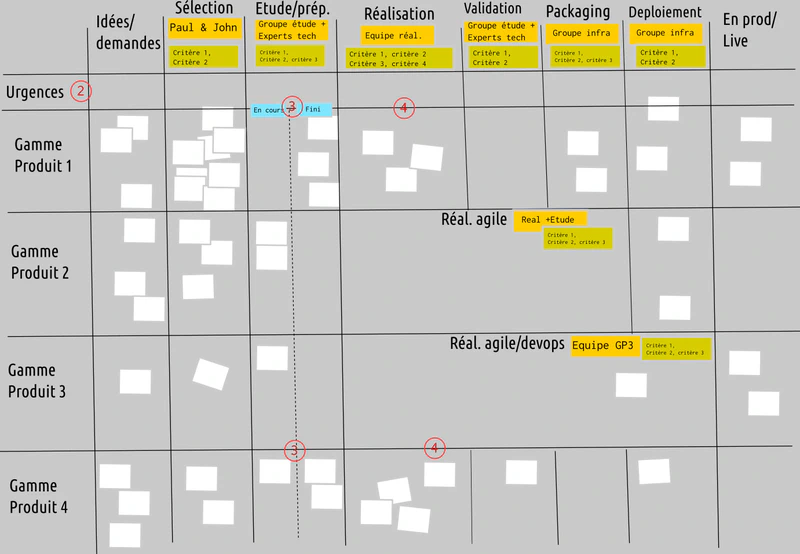

In the examples below I’ve taken the position that the wip excludes the first column which is a dumping ground, and same for the “finished” column. It’s a decision. Do as you like. On the other hand I include a lead time up to “finished”. Click on the images to enlarge.

After that you can dig into Little’s Law but that becomes mathematics, I’m no longer competent. I use kanban more as a tool for continuous improvement than as a mathematical tool for handling flow volatility.

The dumping grounds

Under their guise of introduction and end of journey, the dumping grounds are important. Notably the first one. Often the first column is a jumble of requests, ideas, from multiple origins. It’s better not to restrict it. Let people pour things out, be free, and add elements to it. A kanban, by its concrete, physical aspect, will inevitably make it obvious that among all these things, choices will have to be made. (And often the next column is called “selection”, a first strong act of governance).

The finishing dumping ground often shows the accomplished work, it shouldn’t be neglected.

Learning faster, cost of delay

So we measure the time to traverse and the number of elements handled simultaneously. We’d often like them to traverse faster. We’re bothered by an inert project. We’re irritated, we could have split it into batches, into “releases”, into functionalities. After having chosen what to put in the value creation flow, after having measured the traversal times, we tell ourselves that we should break it into smaller elements to further streamline our work, reach the finished shore more quickly. That was the idea of limits (kanban project portfolio part 1), restricting our activity to force it to move better: start finishing, stop starting. The limits will push us to finish, to finish faster we’re going to break up our value creation into smaller elements.

But why finish faster?

To succeed faster, to fail faster, but especially to learn faster (about one’s market, about one’s offering, about one’s idea, about one’s project, etc.). We find here one of the constants of our complex modern world.

Another measure often linked to the kanban domain is the cost of delay (from memory this article by Derek Huether was good). The cost of delay is the money you lose by not releasing right now a functionality, when you decide to keep it under wraps until the others are ready. So you limit the financial benefits of this delivery by constraining it to the last delivery. In fact you’re losing money (money is often an argument that we hear more easily than that of learning benefits).

Very often kanbans will make this obvious and push you to change in this direction. However, this is not a rule. Often we nonetheless end up with smaller elements that make sense autonomously to better navigate the constraints, finish more quickly, have low costs linked to delay, and which deliver rapid and essential learning.

A kanban often pushes us to no longer think in project or TMA (application maintenance outsourcing) mode, but in product mode (the horizontal lines) and in functionalities or anomalies deposited in this global value / product approach. In fact often we go from project, to “release”, then to functionalities, in the breakdown of our elements. So my kanban project portfolio will therefore probably (but still nothing is certain, respect your reality) push me to think from a product perspective, with elements small enough to gain in learning, minimize my cost of delay, maximize my value and my knowledge.

Pull flow

In kanban project portfolio part 1 I told you about the story of the tickets at the Tokyo park to present the limits that largely define kanban thinking. Here’s another little story for the second part of this thinking (in my eyes): the assembly of car doors at Toyota. I’m someone who mounts car doors, I have a stack of ten doors in front of me. I place one, then two, three, four, five, on the sixth is a little label (a kanban, historically a label) it tells me that I should request ten new doors. Very well, I do so. Then I place the sixth, the seventh, etc. up to the tenth. Things are well done, I requested ten doors at the right time, ten new doors then arrive.

Variant of the scenario: while I’m placing my third door, Jean-Luc interrupts me and asks me for help, which I’m happy to provide for a few hours. When I come back two options, either I use a pull flow with a label on the sixth door that will suggest I request ten more doors, and so my stack of doors hasn’t changed; or I don’t use kanban and I have a classic push flow, that is to say that doors are brought to me regularly and not when I request them (“pull”), and in this case it’s possible that several stacks of ten doors are waiting for me. That’s unfortunate: it’s unnecessary stock, costly (use of raw materials), and risky (if we discover an anomaly it extends to many more elements, if we decide to change our mind, all these elements are obsolete).

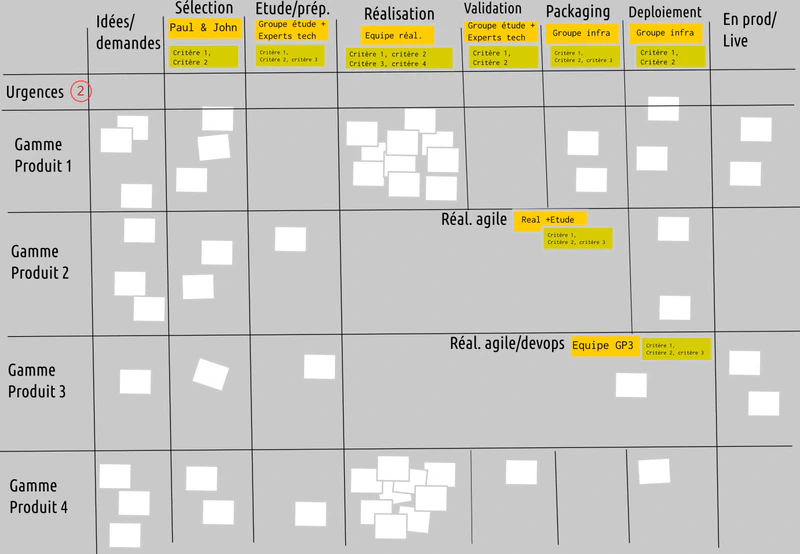

So the pull flow means leaving to the next column the opportunity to come pull the elements from the previous columns when it needs them, thus allowing just-in-time handling much more effective. In a kanban this is represented with two sub-columns: “in progress” and “finished”. The owners of the next column can come pull the elements from the “finished” sub-column of the previous column.

Here’s a little scenario.

#1 blurred vision

A kanban (without limits, or just on the urgent line), but with large irritating clusters in the realization column. Impossible to know if it’s the “study/preparation” column that’s suffocating the “realization” column by pushing (“push”), or if it’s the “realization” column that’s not moving forward (for good or bad reasons: like starting without ever finishing). You must click on the images to enlarge them.

#2 clarified vision

Switching to a pull system will clarify this visibility. In fact there are lots of things waiting, ready to be realized in product line 1, but probably the major part of the effort is being done in product line 4. Still, things are clearer.

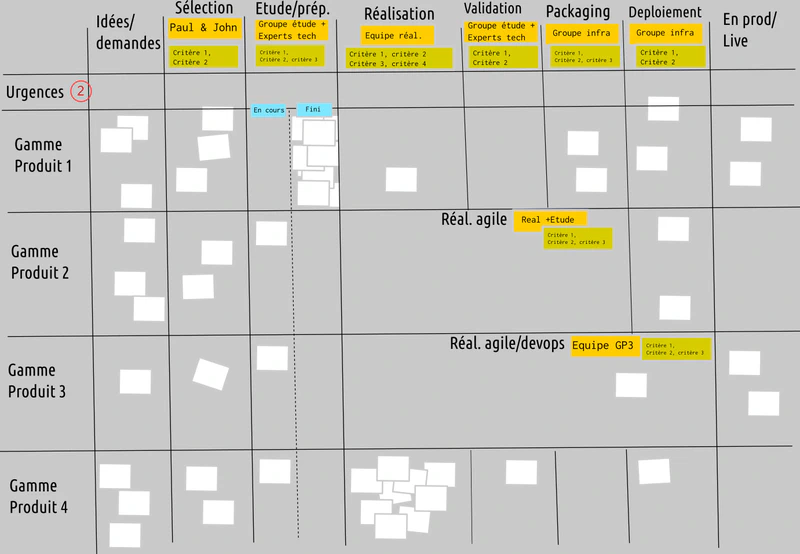

#3 return of limits

Naturally we come back to limits. They will allow the application of a strategy: no need to prepare so much material for product line 1 (for example), by limiting the effort on product line 4 we’re going to free up effort for product line 1 (for example).

#4 The best adaptation

The fourth benefit, perhaps the most important, I can’t represent visually: it’s the team’s adaptation to the need. With the flow the team, and each member that composes it, pulls at the best moment (when they can), and with the best adaptation to the work to be done: they pull what they can and what they want (if some want to try to venture into skills not necessarily mastered they can).

Naturally this can be work in pairs or in groups. Naturally if no one wants to take anything it’s also a strong indication that we need something: strengthen skills? secure the work? That we went too fast in a pull flow system?

There you have it, I hope this second part complements the first well (kanban project portfolio part 1) and will inspire you to try kanban.