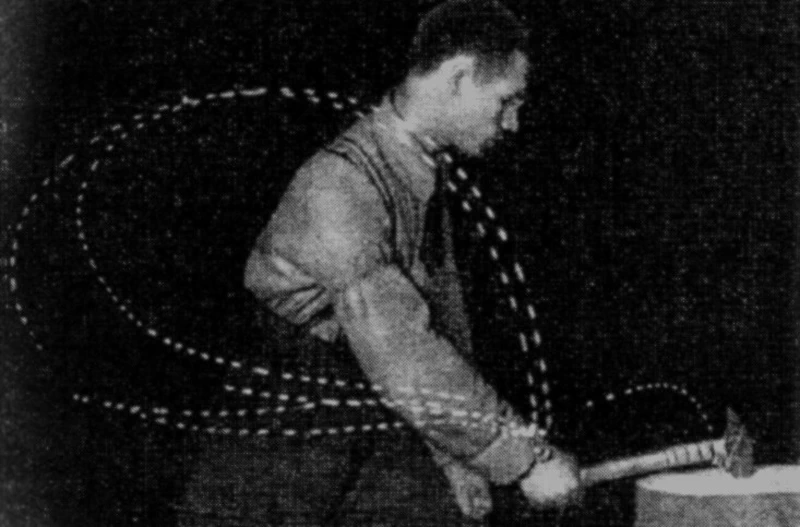

At the beginning of the 20th century, when John Ford announced “people can choose any color for the Ford Model T, as long as it’s black”, he was right, nobody was thinking yet about all the progress and variations that would follow. Ford was revolutionizing the industrial car market, which from that moment on became man’s best friend. Other traits characterized this era and this way of approaching work: labor was very cheap, in surplus, untrained, so we would base our strength on quantity rather than quality; it was the golden age of Taylorism.

At Ford we also observed that the last step before the release of the famous Ford Model T was quality assurance, testing, acceptance in a sense. And we sorted: this car goes out, this one doesn’t. Nothing particularly shocking for the era, raw materials were not in short supply.

And when a car went out you should know that it came with a guide covering the 150 most probable or frequent defects. Again, nothing shocking, at the beginning of this century it was enough to dive into this manual, arm yourself with a good hammer, and you were all set. Repairing the car was not a Chinese puzzle, and remained accessible to ordinary people.

50, 60 years later, at Toyota things had changed considerably. It was a country destroyed by war that we discovered. Raw materials had become a critical element. We couldn’t waste or stock excessively. Machine tools were also a rare commodity, they would have to be exploited to the maximum of their possibilities. In a certain sense, just like the people, who, at the government’s request to rebuild the country, were hired for life by Toyota. The Japanese firm was therefore at the opposite end of the spectrum from Ford’s situation. Finally, technology had also changed, and it continued to change. A hammer was no longer enough to repair your car. Different times, different customs.

Toyota’s response was revolutionary too: to get the best out of its employees, who would accompany it throughout their lives, the firm understood that the best way was to respect them and empower them as much as possible. In fact, it was by empowering them that it got the most out of its machine tools. The man on the ground demonstrated an undeniable ability to adapt these machines and to have ideas for exploiting them optimally. The reflection for continuous improvement became a common practice for them. To overcome the stock problem, Toyota discovered that the best cost would come from two things: a) intrinsic quality: as soon as an anomaly is detected we stop the chain, the impact and correction of this anomaly will be lesser, and the affected stock minimal; b) a just-in-time management regulated by active participation of employees, it’s they who pull the flow (they go get and trigger their actions which thus adapt perfectly to their rhythms and to their skills), and it’s not a pushed flow (where employees suffer the pace).

Between Ford and Toyota, different times, different customs. Observe your organizations, who do they draw inspiration from?

To learn more I recommend reading: The machine that changed the world by Womack, Jones and Roos.