Chapter 1: Agile World, Complex World

“No plan survives first contact with the enemy” – Von Moltke

The purpose of this text is to represent my reflections on the dynamics within our organizations, particularly around my work in organizational coaching. I work with organizations. I aspire to support them, see them grow, adapt, evolve. Like a living organism, they adapt or die. After a century of industrialization, our ideas about organizations are distorted. The model of our parents’ and grandparents’ companies is in bad shape. And that’s a good thing. Because the world has evolved. Naturally or forced by the assaults of our way of life. Different horizons call for different responses, different ways of doing things. I work as a mentor1 or coach of a movement called Agile. The organization is also currently the strongest social bond. That’s where I spend most of my time. That’s where I make most of my encounters. That’s where most of my social interactions take place. Socialization is one of the hallmarks of our species. Let’s be mindful of how we treat it.

Today we must meet three challenges:

- That of the complexity of the recent world.

- Its frugality, the preservation of our resources for our survival.

- And the immateriality provided by technological advances, value is in information, in the knowledge that flows through all networks. I invite you to explore the answers we could bring to these three challenges: complexity, frugality, immateriality. In any case, the modest ones that emerge from my daily activity.

Complexity

Companies, managers think they need time and money, more time, more money.

They are wrong. In the complex, changing, fluctuating world in which we live, having more time or more money doesn’t make the difference. What makes the difference for companies, for managers, is the ability to engage the people they work with, because the gap between the impact produced by a non-engaged person versus an engaged person is immense. What makes the difference is maximizing the value of what we produce by, ideally, minimizing the efforts to produce it.

Forget time and money. Focus on engagement, empowerment, involvement of the people you work with, and make sure very regularly to produce the right things. The current enthusiasm for the term Agile is nothing other than the translation of that.

Agile is ultimately the marketing term for complex. Saying that we want to be Agile is first acknowledging that the world is complex. Complex comes from “to interweave”. Needs evolve, technologies evolve, communication is global, instantaneous. It’s now impossible to deny that things, projects, products will live partly unpredictably, that the unexpected will be there, impossible to have certainties in this complex world. Being agile is knowing how to evolve in this complex world. And, you’ll agree, Agile is an easier term to grasp than “complex”. I doubt you hired a “complex coach” or launched into a “complex transformation”.

So being agile means knowing how to evolve, be performant (another magic word) in this complex world. How is this implemented? The first thing for managers is to learn to let people take responsibility, be autonomous. When a person is empowered, is autonomous, they become much more easily engaged. And engagement considerably multiplies the impact of these people. You know very well yourself that when you suffer things without being able to control them, without wanting to, nor having your say, your performance is, how to put it, very mediocre. At least that’s how it is for me. And if on the contrary you’re engaged by being empowered, having decision-making power, autonomy, you become much more involved, much more performant.

Remember those battlefield stories where generals camped on their hilltops dictating to each of their soldiers or squads the movements and actions they should perform. It’s hard to imagine such a setup today, in a modern war. If a troop or commando has no autonomy, it will be far too slow, far too ineffective, far too vulnerable. Empowering it, giving it autonomy, makes it much more effective, but it’s not letting it free to do what it wants. This imaginary troop does have an objective, it must destroy such bridge, it does have rules to respect: it can’t go to such place, because enemy forces are present, it must not destroy such other structure, etc. It’s no longer the gesture you dictate to your teams, it’s the framework: the objective and the rules that you clarify. It’s up to this team, these people, to take this space, that’s what makes all the difference in terms of performance impact or innovation compared to following a step-by-step, fossilizing process.

Being agile, evolving in this complex world, is therefore first empowering, giving autonomy, giving decision-making power on a whole range of subjects. Modern management is thus first letting go, allowing, and clarifying the framework and rules. But people will only be autonomous, responsible, if they have the right to be wrong. Otherwise your so-called empowerment is a lie. It’s only if you have the right to be wrong that you can serenely always make the decision you think is best. If you don’t have the right to be wrong, your decision is clouded by other considerations, you no longer choose the best one. Here again a fundamental difference is made. For this authorization to be wrong to be easy to give, we’ll try to work on small pieces. If we’re wrong on a small piece, it’s not serious, if we’re wrong on a big piece it’s more annoying, implicitly if you work on big pieces you forbid yourself from being wrong. Small iterations, few things at a time, there are several strategies, but we work on small things to have the implicit authorization to be wrong, we don’t have the trouble of protecting ourselves.

Being agile, evolving in this complex world, is thus empowering, making autonomous, to transform the impact that people can have by taking this space. Authorizing people also means authorizing them to be wrong. This implies a large part of continuous improvement the goal not being to be wrong. To easily authorize people to be wrong, so the prohibition isn’t implicit, we work by iteration, or on few things at a time.

There’s another important parameter that people don’t necessarily grasp. To have a real look, real learning, real observation on what we’ve produced. To make sure not to be wrong and thus say it works, or it doesn’t work. To have this look, this feedback as we’d say in English, and for it to be real, we must observe finished things, things that make sense by themselves, small pieces (we said we worked on small things to authorize error) autonomous that make sense. For example, don’t tell me you’ve prepared all your data model for future financial reports. When adding business objects, the user interface, ergonomic aspects, things will change. We believe we have something finished, but it’s an illusion. We perpetuate the risk of being wrong. It’s not good for anyone. Something finished would have been one of the reports or even more simply a figure from one of the reports, etc., but that would have implemented a piece of interface, a piece of algorithm, business object, a piece of data storage, thus a vertical approach. And especially this small autonomous piece making sense produces value by itself. It already brings something useful by itself.

Being agile, evolving in this complex world, is thus empowering, making autonomous, to transform the impact that people can have by taking this space. Authorizing people also means authorizing them to be wrong. This implies a large part of continuous improvement the goal not being to be wrong. To easily authorize people to be wrong, so the prohibition isn’t implicit, we work by iteration, or on few things at a time. To be sure we’re not wrong we look, provide feedback on the things produced, and to really be able to judge them, these things produced are small autonomous pieces making sense.

For management the change of posture is letting go, allowing. For business people, product people, it’s this ability not to arrive with a globalizing solution, but to know how to break down into small autonomous pieces that make sense, carrying value, and that will gradually expand.

It’s to know how to produce these small autonomous pieces making sense and carrying value that all these organizations are recomposing into multidisciplinary teams: to have this autonomy, this ability to deliver in a very vertical way. Among other reasons.

To this reflection on being agile, on the complex world around us, we must add a parameter: we don’t have time to do everything we’d like to do, we very very rarely have the capacity. Being agile, evolving in a complex world, is therefore also an ability to prioritize by value (learning value, concrete value, etc.). Thus we arrive at the promise of being agile: If I’m capable of empowering and making autonomous I multiply the impact and performance of people, and if I know how to deliver small autonomous pieces making sense, bringing value, and prioritized by it, I know how to read, listen, learn, bounce back on my market. I save by failing quickly. I gain benefits more quickly by not waiting to deliver too large sets of things.

To evolve in this complex world, to be agile do what you want as long as you empower, you make autonomous, thus you will transform people’s impact. Do what you want as long as you have a strong focus on continuous improvement linked to your authorization to fail, to your understanding that good practices emerge in this changing world. Do what you want as long as you have real feedback a real look at finished things making sense, not on the number of features you’ve deployed, not on the number of hours you’ve spent, but on the number of additional users, on the number of phone calls to the hotline linked to your last delivery, etc. Measures often external and not internal. Thus if you’re able to prioritize these small autonomous elements making sense and carrying value you’ll know how to read, learn, bounce back on your market at lower cost and quickly gaining benefits. That’s the promise of agile.

You don’t have a time and money problem. You have a problem with the impact of your collaborators who aren’t empowered enough, who don’t have enough autonomy, and you have a problem to maximize value: you’re not capable of reacting, learning vis-à-vis the market.

Everywhere flourish the invocations: be happy, be motivated, be involved, be responsible, be happy, happiness chief blabla. But this can’t be decreed. Regarding engagement, regarding involvement, it’s not an injunction to which we can respond. You can’t decide to make such and such person motivated. But you can create a framework, a context, that allow these people to be motivated, involved. We regularly see this message come back: a very small part of employees in the world feel involved.

In the agile manifesto there’s a principle where it’s written: do projects with motivated people. Generally we laugh at that moment. Naturally projects work with motivated people. What an idea! So forget everything else, focus on the idea of engaging the people you work with.

Some explain that between an engaged person and a non-engaged person the difference is enormous. In the Mythical Man Month the author (Fred Brooks) expresses the idea that a person (in this case in his context, a software developer) has a productivity ratio of one to ten depending on the context. Their capacity would thus fluctuate from one to ten depending on the context. My observations - on myself and others - tend to confirm this information. And I think the large part of this gap comes from the person’s involvement. Observe yourself performing a task on which you don’t feel involved, and one on which you feel involved, that you’ve appropriated. Personally I go from dejected nonchalant uninspired to frenzied bulldozer highly productive.

We can’t decree motivation, nor involvement, nor appropriation. Yet there’s a field, subject of study, where we discover involved, engaged people. With a high level of requirement. When something fails, they try other ways, don’t let themselves be defeated, they like to look for alternatives. Even the most introverted among them call friends for help or go read the documentation. Because – must it be mentioned? – the online documentation is plethoric: guide for the “newbie”, videos, support, wikis, forums. But what is this field? The people I’m talking about spend several hours per week there, even several dozen hours, and, cherry on the cake, they pay for it…

It’s about video games, and rather video game players. So why this involvement in this field? It’s exactly what we’re looking for in our organizations. All these online game players who pay to fail, start over, learn, redo, provide quality documentation, couldn’t we have the same engagement in business? The video game industry is flourishing, understand it involves enormous sums of money. Therefore before drawing lessons for the organization ourselves, it questioned itself, because its success is linked to the involvement it will generate. The observations that flowed from this research are a goldmine for us. To see: Jane McGonigal and to read: Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World by the same person.

But as I mention this subject, I receive my eldest son Mathieu’s report card. Mathieu has good school results, but the report indicates that if Mathieu were involved he would have very good school results. I look for Mathieu:

- Mathieu? Mathieu?

- (from the other room) Yes dad?

- Can you come so we can talk about your report card.

- Wait, I can’t right now, I’m building the fourth tower of my castle at Minecraft and it doesn’t have exactly the same decorations as the others, nor the same iron constitution, I can’t leave it like that.

- Yes that’s exactly what I want to talk to you about…

In other words Mathieu is very involved in his game, and his results are very good. What’s missing at school to harvest this same engagement? What’s missing in organizations to have this same type of involvement?

It’s not already competition or the desire to win that will make this difference. I don’t believe we really win at Tetris or Candy Crush Saga, nor really at any of my son’s online games, he loses as much as he wins, that’s not his real quest. What we need and what these studies on video games teach us is desperately simple to state, but devilishly difficult to implement.

A clear objective

First a game that engages has a clear objective. Have fun testing if your project, your product, your organization has a clear objective. Easily stated. Think back to this famous Einstein quote: “if you can’t explain it to an eight-year-old, it’s that you don’t know what you want”. Your work as leaders, as managers, is this clarification.

Clear rules

I can’t cast a spell if I have no more mana points, I can’t combine the power of these two weapons, but hey I could use houses to protect my tower and not the reverse. To take this space that will make all the difference, it’s appropriate to clarify the target, the objective, but also to delimit the framework in which we can flourish, surprise, imagine, appropriate. You must clarify the rules of the game. Naturally if your rules are too constraining the space you’ll propose will be weak.

Feedback, a return look

If I kill this monster I get 100 points, if I take this city I gain 10000 crowns, oh darn there was nothing in this dungeon. In the game we constantly know the benefits (substantial or catastrophic) that our actions entail. In the organization it should be the same. I delivered this feature, but it received no favorable welcome, whereas the other yes, but not in the expected way. Yes this action was received positively, that one not, this one triggered that, the other that. Whatever the result of your activity, you should measure it and know it, make it known. Without that your involvement will reduce. What’s the point of working if we don’t know what becomes of the fruit of our labor. The first step towards meaning is this feedback.

Invitation

More difficult. None of the video game players are obliged to play. Ideally none of the members of the organization should be obliged to come get involved, work. Not easy. We run up against another reality, that of Maslow’s pyramid, we must first have a roof, eat, in short… have an organization and a salary before thinking about engagement. It’s a vast debate. But difficult today to invite to work, in any case not simple depending on contexts. So how to use the notion of invitation?

Let’s take some examples. Jim McCarthy, the very one of the core protocols led Microsoft Studio for a time. Facing all his teams he tried invitation: here are 15 projects*[1]*, “propose the teams you want for the projects to be successes”. Turmoil among managers. People will do anything. But no. We are living systems insists Harrison Owen (the inventor of openspace), we are naturally responsible. It’s by disempowering people that you sometimes get completely absurd behaviors. In this framework and following the clearly stated objective: “for the projects to be successes” people intelligently mixed socialization (group dynamics, friends) and skills. But especially crucial effect of invitation – of transparency on the reality of things: nobody will volunteer for certain projects. If there are two projects “that stink”, they’ll find themselves without anyone. That’s very good news. We discover there are clearly complicated subjects, perhaps with surprise. Not that these projects shouldn’t be done, but it becomes clear they need other means.

Another example, inspired by Dan Mezick, use invitation in your meetings. Imagine the big boss who proposes a really invited meeting. This big boss, we’ll call him Mesmaeker (Gaston Lagaffe…), invites twelve people. First option: nobody shows up. And that’s good news, because it was really a useless meeting. Everyone saved time. Second option: nobody shows up yet it was a useful meeting. The learning is clear for Mr Mesmaeker, he must rework his communication to make people understand the importance, the stakes of this meeting. There, manifestly, his communication is ineffective. Third option: nobody shows up yet it was a useful meeting, and its importance was understood. But maybe the priority wasn’t clear. We all have important things to do. Mr Mesmaeker should have specified: and “it’s a priority”, or “it’s more important than…”. Another question, communication problem made visible by invitation. Fourth option: four people show up out of twelve. It’s the four “right people”, because they’re the ones who understood the importance, who are ready to invest, who prioritized the importance to put this subject forward (those who have time). Fifth option: the one you all know, it’s not a real invitation, all twelve people are there. They say yes “as it should be”. But we don’t know which ones have time, understood the importance, integrated the right priority, we don’t make necessary effort on the meeting format since everyone is constrained. And everyone says yes, but we don’t really know what that means.

You’ve understood invitation is key for engagement (and therefore change management). But for our organizations it’s especially also a formidable transparency tool.

Invitation is also one of the pillars of the open agile adoption or openspace agility approach. The idea is to invite everyone to an open forum cyclically, an open forum that has an objective and a framework (well well), to invite everyone to give the how of implementation. Thus we obtain something very engaging and very respectful of people and organizations. I refer you to openspace agility/open agile adoption: here

Thus again, you don’t have a time and money problem. You have a question of involvement and engagement. And under these fairly simple precepts: clear objective, clear rules, feedback and invitation, hides a spectacular lever. But for leaders, managers, leaders, it’s constant work to clarify, support, evolve, support these clear objectives, these clear rules, this feedback and this invitation.

When Dan Mezick told me about these ideas on engagement inspired by the world of video game players, around 2013, he often followed up by also citing teachings from Tony Hsieh the leader of Zappos (when Zappos was a symbol of success). These four other elements I’m going to give you complemented, reinforced the previous points (being engaged - part 1). It’s with the years that I really understood that this second list balanced the first as much: safeguard, resonance.

Here are the four points in resonance with those mentioned previously. To be involved, engaged, you need:

A sense of control

It’s the safeguard of the clear rules mentioned in the first series on engagement (being engaged - part 1). In it I talked to you about a framework, linked to a clear objective, and clear rules that helped take space, get involved, engage. They imply on the condition they don’t hinder autonomy too much. They’re there to give autonomy, not constrain it. It’s about a sense of control of one’s work tool, not control of the other. Imagine an individual in a group who starts their activity and must ask such other group for access to resources, machines, such other group for security rights, production deployment, access to such data… who can’t really manipulate their work tool, because their jurisdiction is fragmented. No sense of control of their work tool, loss of their involvement. That’s why often in an agile world we seek “feature teams”, multidisciplinary teams, they possess a capacity for autonomy, they control their perimeter. People must be able to appropriate their perimeter. Clear rules, but which preserve autonomy.

A sense of progress

There it’s simply the echo of the feedback idea I mentioned previously. It should encourage engagement we should regularly know what we produce, generate, obtain. We should (very) regularly measure. For that we should (very) regularly finish things. And thus through this need for a sense of progress I’d like to sensitize people not to work on too many elements at once. Multitasking is very harmful to our productivity. See this diagram: with one task I’m normal, with two I’m better, because I can switch from one to the other during incompressible delays. With three my productivity is generally already below what I have treating one task at a time. If I go to four or five it becomes the Berezina.

I come to tell organizations: “stop working on ten projects at once, focus on the three most important”. Sometimes people answer me, wryly, “but Pablo it was the 8,9,10 that allowed to pay you”. So I resume (eh eh): “stop the seventh you’ll finish it faster”. It’s a coherent global approach: if you know how to break down into small pieces your projects/products, you’ll know how to deliver substantial marrow in a shorter time span, and move to the next. You start the next later, but with much stronger focus, and also this ability to condense value in a reduced scope. And so on.

To be engaged, you must keep a sense of progress, nourished by feedback, you must know how to be focused on a reduced number of activities.

Belonging to a community

With invitation we enter a group, a family, a team. It’s a welcome. Belonging to a community seems obvious to feel engaged, involved. It is, obvious. I take this opportunity to come back to what makes a group, a team, on some important figures. These figures I mentioned in the agile horde, in 2013.

Dunbar’s number

Dunbar is a sociologist/anthropologist, he notes that prehistoric villages split around 150/220 people, suggesting our physiology forbids us from having more than 150/220 real social connections. So if I want to encourage a sense of belonging to a community I’ll limit my “divisions, departments, agencies” to 150/220 people.

Pleasure of belonging to a group

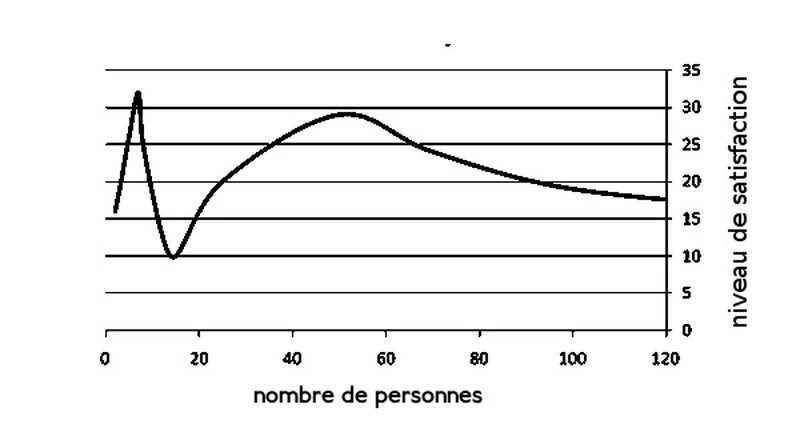

With Christopher Allen’s research, we discuss the pleasure of belonging to a group, what number triggers this satisfaction? The adjacent table indicates that the best feeling of satisfaction, which will support a sense of belonging, is felt around 7 and 50. So if I’m a leader, I’ll break down my organization into divisions of 150/220, then departments of 50, then teams of 7.

Often that’s the moment when someone says you can’t thus do “big projects”, “large products” with a team of 7 for lack of capacity. Maybe, but with 7 teams of 7 we can. Naturally “big projects” entail a need for synchronization (that’s the whole issue of agile at scale, culture and synchronization), but it’s much easier to synchronize 7 teams of 7, than to work “in rake” with 50 people.

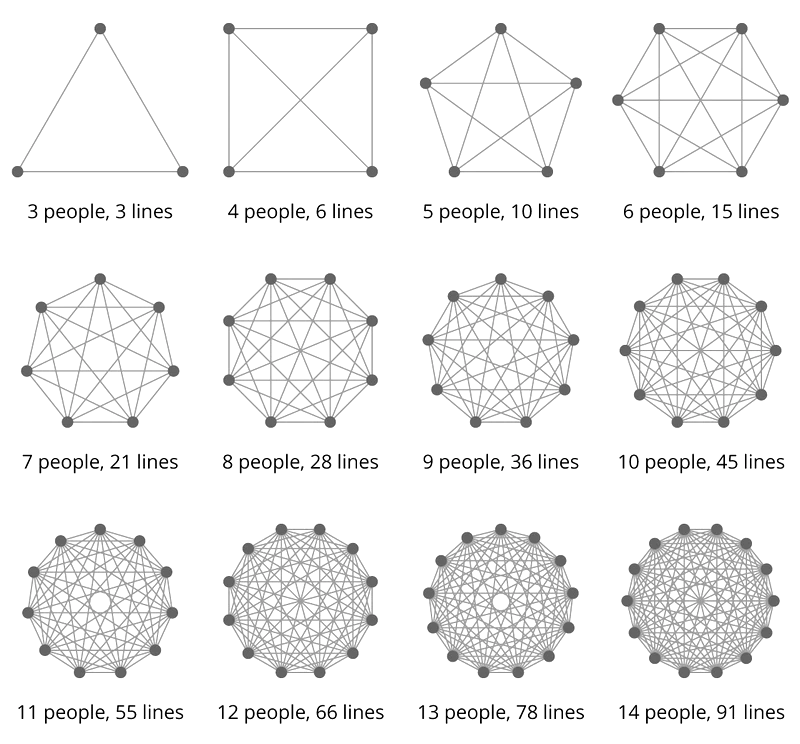

Interactive communications

Finally the number 7 is corroborated by Fred Brooks’ observation (in the old and famous “mythical man month”), which visually demonstrates that the number of interactions becomes unsustainable as soon as we cross the bar of 7/9 people. That is to say that real communication and team dynamics is built… from 4 (from four sensation of team, with that it’s still individualities, it’s not negative however), up to 8. Beyond 8 we observe that interactive communications split into two groups.

Thus therefore in search of a sense of belonging I’ll decline my organization into groups of 150/220, then 50, finally teams of 4 to 8. Thus my involvement and engagement will be better.

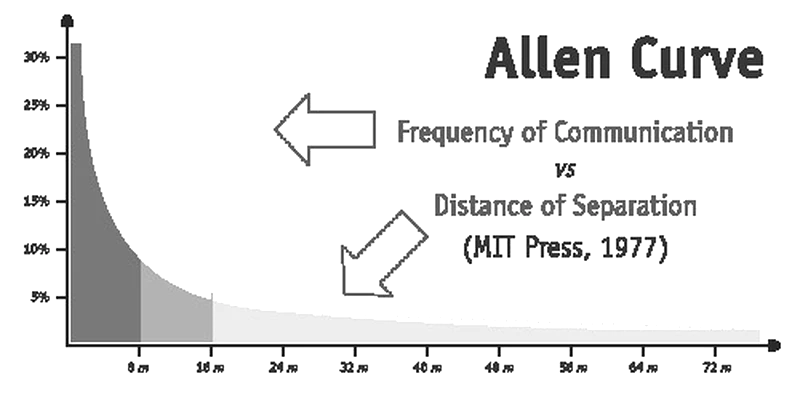

Allen curve

Since we’re talking about communication quality, I often specify that co-location is key. This observation is supported by “official” studies (from IBM!) which describe that beyond 15m communication collapses. Alistair Cockburn uses the following metaphor: beyond the distance of a bus communication collapses.

These last years I could question this question of distance and co-location, because technological novelties can make it invisible. Under the cover of several conditions, but that’s probably the subject of another article.

Working for something that surpasses us, greater than ourselves

We had talked about a clear objective to engage video game players. In “real life” – as we often hear – it must be inhabited by meaning. It’s the fable of the stone cutter, I’m engaged if I’m not simply cutting a stone, or even if I’m only doing that to feed my family, I’m engaged, involved, if I see the cathedral we’re building through my cutting.

Conclusion

I resume as I said in this series past writings, which still seem current to me with current and recent conversations. I’ll continue this reflection work.

To conclude on engagement: a clear objective that is inhabited by meaning, clear rules, but which leave enough space for autonomy and sense of control, feedback that allows a regular sense of progress, an invitation and the conditions for group dynamics.

-

I prefer mentor (“Attentive and wise guide, experienced advisor” says the Larousse) to coach (ambivalent and pretentious in my eyes, I don’t feel like changing you, neither the competence, nor the right, nor the desire). ↩︎