Here is the third and final part on decisions, the last chapter “released” from the small manual of organizational thinking, on the right time to make decisions. I recommend reading the other chapters as a complement.

I’m adding a new diagram at the end of the article that is not in the book.

… (You should have read the book first, but I’ll let you grasp at straws…)

This work on an achievement that develops over time – as opposed to an “all or nothing” achievement with a final revelation of the project when it’s completed – causes a change in rhythm, a different temporality. This change in rhythm is an evolution that will strike you so much that it will break with your habits.

Moving forward, delivering, finishing step by step, over time, has nothing in common with a huge final assembly. You will have understood that delivering everything at once at the end of the journey carries enormous risks. You will have understood that delivering over time, in addition to limiting risks, allows you to obtain benefits much earlier.

This way of proceeding is not new; one could almost say it was forgotten with the division of labor of the industrial era, and its need to transform everything into procedures, then rediscovered in the Japanese car assembly lines of the post-war period (World War II). At that time, the Japanese production apparatus was completely destroyed and car factories had to reinvent themselves: they were no longer equipped enough for such intensive division of labor. They had to rethink themselves to work with what they had and hunt down every waste (because they no longer had raw materials either; this is a scenario that could happen in 2052). These factories consequently had to make every new idea flourish; it was the frugality of the environment that demanded this. It was a prosperous period that would influence the way of manufacturing cars, and even all industries, for decades. From these lessons, I keep two particularly in mind. Two of the “leitmotifs” of this approach are:

- Show as early as possible

- Decide as late as possible

I must give you these two sentences together, because their propositions complement each other. When I talked to you about breaking things down and having finished things regularly that are usable, manipulable, functional; and that this way of breaking down the achievement allowed learning as you go, and benefiting from the value over time, meaning earlier, as soon as possible.

As soon as we have something (an idea, an achievement, a result): we show it. Thus we receive this feedback, it engages us, and we learn, we adjust, we optimize, because showing it implies interactions, and interactions are a source of enrichment. But again, what you show must make sense, must be something that can be judged. And the more operational it is, the more complete it is while being a small piece, the more useful feedback you will have.

Any organized human activity, from pottery to sending a man to the Moon, must meet fundamental and contradictory requirements: the division of labor between the different tasks to be accomplished and the coordination of these tasks for the accomplishment of the work, Mintzberg tells us. Here too we find a contradictory requirement: working on small pieces, to limit the risk to the size of the piece, and delivering, manufacturing, showing things that are autonomous, operational, by themselves.

If you show a piece of a whole, perhaps this piece says nothing by itself and brings nothing by itself. But if you already have a functional whole and you change its functioning — thanks to this new piece —, then yes it brings meaning, and the benefits I mention.

Keep in mind: show as early as possible. We could reverse the proposition to better understand it: the longer I hide things, the more I increase the surprise effect (and perhaps desire this in a competitive context), but the more I forbid myself enrichment from the outside, and the more I risk discovering late that I am wrong (or in the useless).

What disturbs some people about showing as early as possible is being judged for something unfinished, incomplete (a concern, for example, nowadays with academics). We find ourselves once again confronted with our desire to be perfect. It is therefore also fundamental in your environments to ensure that everyone can be wrong without it being a problem. I have already mentioned this, but it’s worth repeating. Remember that a first idea is to work on small elements, because it is acceptable in people’s minds to be wrong about small elements; we feel authorized. Working on small elements gives implicit permission to make choices, make decisions; it feeds our feeling of control and engages us more.

You must therefore verify that it is possible in your environment (in our ecovillage of 2052), that it is accepted to be wrong, to propose incomplete things, that we can go back. Otherwise it’s a significant brake.

The other key phrase is: “Decide as late as possible”

That too is usually quite a bombshell in the pond of our certainties. To better understand this phrase, we can look at the real options movement. Real options are originally a financial tool. Chris Matts and Olav Maassen transposed the idea of these real options to the world of organization. Their concept is ultimately quite simple:

For any decision to be made, there are three categories of possible decisions, namely a “good decision,” a “bad decision,” and “no decision.” Most people think there are only two: either you are right or you are wrong. Since we normally don’t know which is the right or wrong decision, the optimal decision is actually “no decision,” because it defers commitment until we have more information to make a more informed decision.

However, if we observe the behavior of most people, we find that an aversion to uncertainty causes people to make decisions early. Real options respond to this aversion to uncertainty by defining the exact date or conditions to be met before making the decision. Instead of saying “not yet,” the real options approach says “Make the decision when…” (Author’s note: meaning when such and such criteria are met). This gives people certainty about when the decision will be made and, consequently, they are more comfortable delaying the decision. Delaying commitments gives decision-makers greater flexibility because they continue to have options. It allows them to manage risk/uncertainty by using their options.

You note that our concern is still the notion of perfection, the notion of completeness, risk aversion: we don’t know, and everyone wants to avoid this feeling of not knowing. Again in this uncertain world, it is normal not to know. We must be able to display it, play with this uncertainty. But I’m not telling you to be only in uncertainty, not at all, it’s unbearable, exhausting. Real options are a form of reassurance; rather than simply saying “we don’t know,” we give ourselves criteria to go further, to decide later.

Understand the phrase decide as late as possible as a chance to learn as much as possible before deciding, to replace your hypotheses with tangible answers as much as possible, and this is done by showing as early as possible. And we come back to all this work of breaking down – at the right pace (not too early) and at the right time (prioritized by value, learning) – which also authorizes the right to be wrong.

There is, however, a danger in deciding as late as possible: it’s deciding too late. Letting the opportunity pass, your chance, the moment. The phrase has a second part that recalls this risk: “Decide as late as possible … at the last responsible moment.” This last responsible moment is the instant before, or just before the opportunity passes, when this wait becomes a handicap rather than a support. The longer we wait, the more we learn. But if we wait too long, it generates a cost. In the ecovillage, you’re going to install a dam on the river for many good reasons, but you must wait until the last responsible moment in autumn to see the true course of the river. The more time passes, the more you see exactly what will be necessary for this dam. But if you let the last responsible moment pass, suddenly the river has become too big and it becomes impossible or much harder to build the dam.

Every time you do something that needs the eyes of others, that is intended for others, ask yourself: have I shown it early enough? Every time a decision must be made, ask yourself, would other intermediate actions allow us to know more before making this decision?

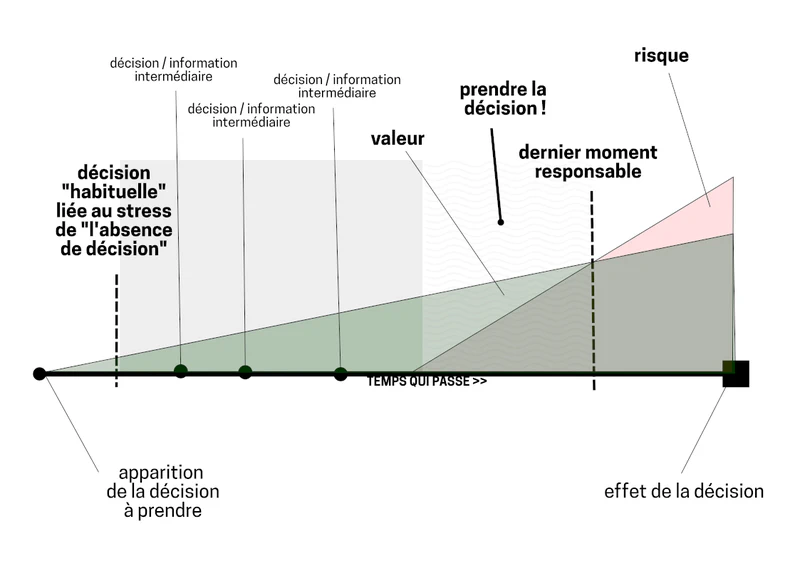

I’m therefore completing this paragraph with this diagram:

- The long rising green slope represents our level of knowledge of the subject that increases, and therefore the value of the decision that increases.

- The rapid triangle that appears in red is the emergence of risk linked to the absence (or the wrong decision)

For the rest, you have the elements of reflection in the text; it’s up to you to seize the right moment for the decision.