I’m perhaps starting a new series of articles here. In any case, this article will have a very personal resonance.

A few months ago I stumbled upon a film documentary about a man crossing the Atlas, the Amazigh country (Morocco) around 1952/1953. I shuddered. I told myself that it was very close to the period when my father arrived in Morocco, in that area, and that perhaps I would catch a glimpse of him. It awakened in me a need to know more about this period of my father’s life. I knew my father from my birth (well, obviously), until his death, when I was 35. 35 years of happiness, with the signal honor of having the two most extraordinary parents in the world. With that, life has been, and will be beautiful, until my death.

This period of my father’s life that I know little about is strange, at least very foreign to me—he was a Benedictine monk for 25 years from age 17 to 43. I’m an atheist, educated by the Dutch and anticlerical side of the family. And he never insisted or pressed the idea of believing, on the contrary, it was rather my mother, a convinced anticlerical, who pushed us to read the Bible in comic book form for its cultural aspect.

And yet my father wrote a book that traces his life, at least until he left religion and met my mother. Which I’ve read and reread, especially the historical part. And yet I missed a lot of things. Watching this film about the Amazigh country, about the Atlas of Morocco, I had a burning need to dive back into my father’s life, so extraordinary that 35 years aren’t enough, and I still miss 20 more years by his side.

The context

So I opened the archive boxes, the photos, the letters. I found 1000 photos (that’s approximately the number) that were fascinating. I’m going to share these photos soon, because my father didn’t have a classic monk’s existence. Benedictines are normally cloistered monks. This was far from the case for my father. I’m not going to get into certain analyses here, maybe in another article, but you should know that my father was from 1956 to 1966 a monk at the monastery of Toumliline in Morocco near Azrou (Amazigh country, in the Atlas). He was cellarer there (financial management) and above all the organizer of the international conferences of Toumliline. Right-hand man of the Prior who conceived these conferences, my father was the one who organized them, the doer, the maker. He became its Prior (the leader) in 1954. And left in 1956. Toumliline, at that time, was about the question of liberation of the Moroccan protectorate from France. Against all expectations, the monastery positioned itself as an element of strong neutrality that welcomed Moroccans and didn’t support French colonialism at all. I’ll let you dig around Toumliline if you wish, in recent years there’s been a sort of revival because Morocco realizes it let slip away a place whose intellectual and historical brilliance is important.

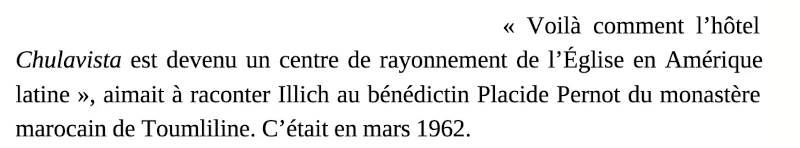

Toumliline is said to be the first African think tank, the second library in the country. At the conferences, hundreds of people of all ages, professions and faiths (it’s monks organizing after all…) came to discuss freely. Mehdi Ben Barka was there, as well as many other Moroccan, French, and international political or intellectual figures. My father’s role was also to travel to find funding for these conferences. On his route he spoke and conversed with Robert Kennedy, Mother Teresa, Amadou Hampâté Bâ (Bouaké conferences which he also created), Michel Leiris, etc., etc. … and Ivan Illich.

Because Ivan Illich is first of all CIDOC and Cuernavaca. If Toumliline was probably locked into a too religious vision through its approach—they’re monks after all (and I see my father struggling in this habit)—Illich’s Cuernavaca is much more academic, open. It doesn’t seem to me that Illich struggled against his status as a priest (that’s already different from a Benedictine monk, normally cloistered), his subject isn’t religion (even if its presence is undeniable in many of his analyses), his subject is thinking about the world. At Toumliline it seems to me they thought about dialogue between religions, or in any case, there was as a postulate the presence of religion in the subjects. This isn’t the case at Cuernavaca. And Cuernavaca appears after Toumliline. But to my eyes this takes shape as a logical continuation.

I’m reading “Ivan Illich, l’homme qui a libéré l’avenir,” by Jean-Michel Djian. And I come across passages where he mentions my father. (I fall off my chair). (oh yes all monks take a pseudonym, my father’s was placide, but his real name is Jacques Pernot).

Source: Ivan Illich; l’homme qui a libéré l’avenir, Jean-Michel Djian.

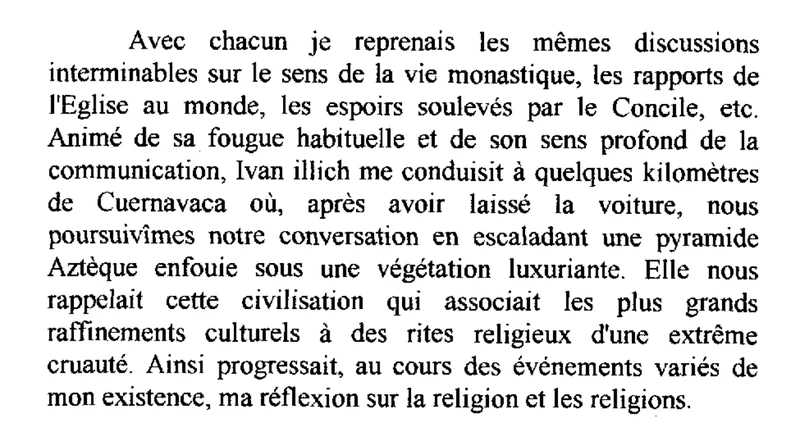

What, he spoke to Illich??? Actually that seems very logical, I’m telling you these two centers of reflection, although different, had many similarities. And I reread once again my father’s pseudo-biography, but yes, how could I have missed it!

Source: La religion revisitée, Jacques Pernot

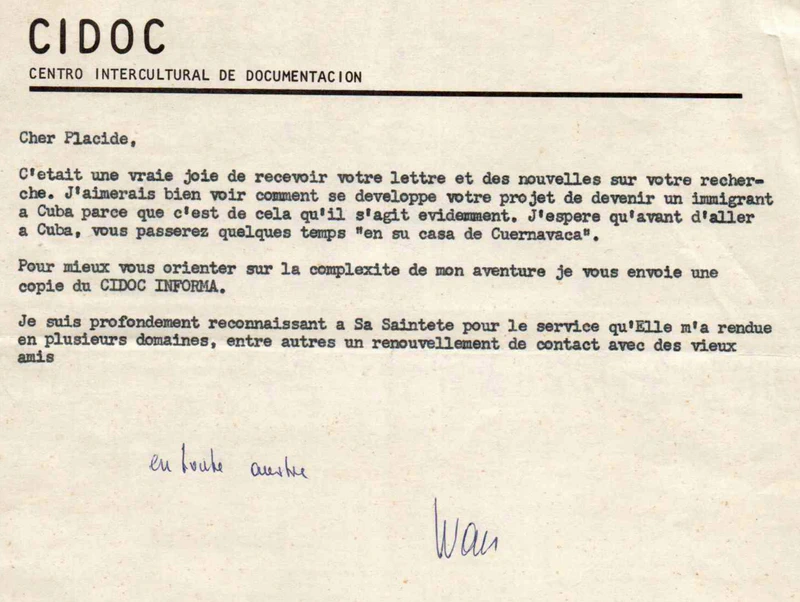

And then I come across a letter from Illich congratulating my father on leaving for Cuba (with my mother, and me who would be born there 18 months later). He was going to work there for CII Honeywell Bull (computing).

Source: personal correspondence

A bit stunned by everything I’m finding (if you’re interested in these archives, let me know, particularly concerning Toumliline), I immerse myself in reading Illich. Because if my father was a doer, a maker, bubbling with activity, Illich is definitely a thinker. A prophet, my father calls him (and many have called him that).

Autonomy

I’m a bit annoyed with Illich for having called one of his most famous pamphlets “conviviality.” And I’m annoyed with the people who have presented this term since for not warning us: “this is absolutely not about conviviality as we understand the term.” And I’m annoyed with myself for not having been able to access it before this recent rewind.

The real subject under Illich’s conviviality is the refusal of humanity’s overflow by its creations: technical, computing, administrative, mechanical, etc.

Illich’s subject is autonomy. It’s the pleasure, the joy, the motivation and engagement, the meaning, that are given by ways of living over which we have control (to use Jane McGonigal’s ideas reformulated by Daniel Mezick). Control of our work tool. Mastery of our work and life environment (to use the term mastery from Daniel Pink’s book drive).

Nassim Taleb’s skin in the game, Taiichi Ohno’s Gemba, all of this could easily be read through the crusade that Illich had launched against the bureaucratic or technical dehumanization of man by man.

Threshold effects

With the importance of autonomy and proximity, of the long term, also comes the importance of the notion of threshold. What is good at small scale, declines, brings dismay, derails, rebound effect, at large scale. Systems thinking without doubt. Or again Nassim Taleb’s antifragile.

Too big a team, too big a deployment, generalization of a system, democracy, education, medicine—at what point do we lose the meaning and interest of the thing, to be devoured by its side effects?

He’s modern before everyone else. He responds about AI, social networks, and other subjects (he died in 2002).

I don’t agree with everything, but I’m very attracted.

This article expresses as much a personal journey of reunion with a part of my father’s life, as the pleasure of having stumbled upon this avant-garde thinker who can help me (and perhaps others) answer current questions I’m asking myself. About organization, human dynamics, he completes and strengthens certain convictions, about what could happen and what will probably come: a rupture without revolution, he makes me look somewhere again.

He didn’t see everything, but he saw a lot.

Pamphlet

That’s why I’m telling you about him. Because his words strike hard. “Conviviality” is a pamphlet. Everyone takes a hit. With each part we say to ourselves “damn he hits the bullseye.” And he succeeds without dragging us into a political bias.

“The organization of the entire economy for the sake of better-being is the major obstacle to well-being”, Ivan Illich (Conviviality).

Naturally to finish, I imagine him, him and my father, talking about their journey, both smiling (both smile easily), on the ruins of an Aztec pyramid.