First, I’m pleased to announce that the masterclass on Product Management with Rachel Dubois is out. You have all the information on the landing page, and the masterclass page: the detailed program, prices, video excerpts. It’s an offering I’m proud of and I hope you’ll take the time to look into it.

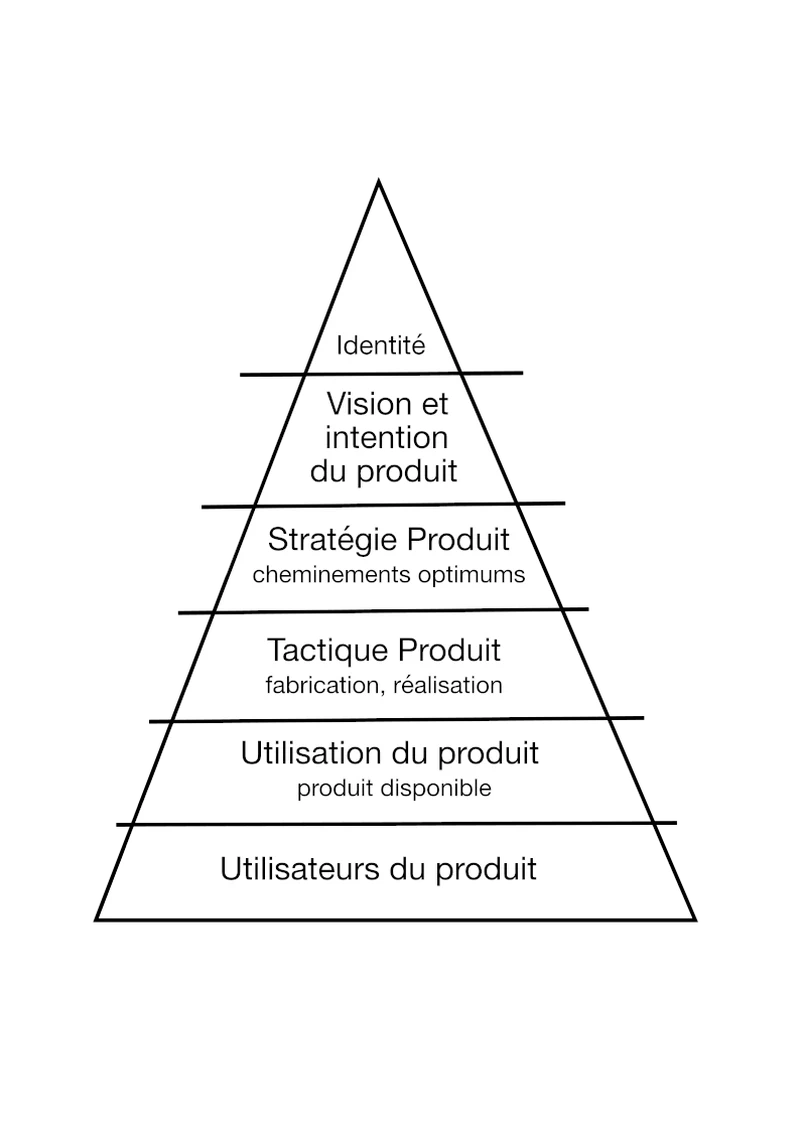

In this masterclass I propose a tool I call the product management pyramid. It’s simple, nothing groundbreaking, and it’s the reuse of concepts well known elsewhere: the use of Bateson’s logical levels (taken up for example in Dilts’ pyramid), and especially the idea of where to look for the resolution of a level in difficulty. Let me explain.

There is in this idea of logical levels, different levels of understanding, different perspectives, but like sedimentation: we traverse the levels coherently. What comes from the upper level normally cascades coherently to the lower level. I say normally, because precisely the incoherences between levels are sources of problems.

Levels of a product management pyramid

We could define the levels of a product management pyramid as follows:

First, the identity of the organization that creates manufactures brings to life the product. Who is it? What is its meaning? Who composes it?

Then this organization has a vision concerning a product, this vision naturally emanates from its identity. This vision is a purpose, an intention.

From this vision, it projects a strategy (which continually adapts): the optimal paths to reach its purpose, its intention.

By following these paths, this strategy, we manufacture, we realize this product, in any case the strategic elements of this product. We implement realization tactics.

When the product is manufactured (continuously, in an ongoing way obviously today) it is put in the hands of users, to be used, and implement the purpose, the intention for which it was designed.

This set of experiences constitutes the family of product users. As in Dilts’ pyramid, with Bateson’s logical levels, the last level is a receptacle that could be expressed in the past or in a static way (I don’t know how you best perceive the idea): here are all the users and experiences around the product.

Coherence between levels

A coherent product will see a reading that flows naturally between who we are, and therefore what we want, and therefore the strategic paths chosen, and therefore our manufacturing tactics, and depending on our manufacturing tactics how / at what pace / and what we put in the hands of our users and thus what bases of users and experiences are constituted.

And as often in this type of pyramid you will have noted that the three “top” levels are more about principles, values, ideas, and the three “bottom” levels about putting into action, behaviors, results.

Incoherences between levels.

If there are incoherences between levels, a dissonance, you’re heading for problems.

For example, if you have created opportunity solution trees to highlight key experiments for solving problems/opportunities that you consider priority, you expect the manufacturing tactics to go straight to the point on these, that you can quickly validate, invalidate the experiment. If this is not the case, you have a problem: loss of time, misunderstanding, difficulty, reading of results.

For example, if you have an intention X and your strategy doesn’t address it… you clearly have a problem.

For example, if putting it in the user’s hands is chaotic and poorly managed (bugs, poor ergonomics, etc.) you have an issue with your user base and experiences (which you hope are positive).

So you’re looking for fluid and coherent logic between levels.

Resolving a problem at a level

With the last example, we highlight another rule of this type of pyramid. When you have an issue at a level, the problem probably comes from the upper levels (and therefore that’s where it needs to be fixed).

My user base is not satisfied because putting the product in their hands is not satisfactory. That’s where I need to work.

Or perhaps putting the product in hands is not satisfactory because the manufacturing tactics are not satisfactory (no tests, no adequate breakdown, etc.).

Or perhaps (I go up until I find the source): the manufacturing tactics are not satisfactory, because the strategic paths are deficient (poorly thought out, poorly expressed, etc.).

Or perhaps my strategy is deficient because it’s based on a vision, a purpose, an intention poorly expressed, obsolete, poorly thought out.

Or perhaps my purpose, my intention, doesn’t work because they don’t stem at all from who we are and how we are constituted. Knowing ourselves, there is no sense in having this vision.

There you have it, I hope you’ll dive into this masterclass or that you’ll read my small manual of organizational thinking which also discusses it.

Read more:

- I had already mentioned this type of pyramid in my article on harmonization of the organization in 2019.

- And it’s also a subject I revisited and adapted in my book small manual of organizational thinking.