13 years ago, in November 2012, I recounted a conversation (which was also a conference) I had with Alexis Beuve from Praxeo (Alexis whom I had met at a client I extensively supported at the time). This conversation was about the product owner strategy (at the time all the titles product owner, product manager, head of product, chief product officer, product leader had not yet emerged).

Alexis is a specialist in strategy games (go, chess) among other things, and also a publisher and author. We had reflected on applying the strategy of these players transposed to thinking for product *ers. I found it interesting, and I think it fell into oblivion too quickly, which is why I’m writing about it again today (I haven’t seen Alexis for a good ten years and I salute him on this occasion).

First, if you want to attack the mountain from its most arduous side (but probably the most enriching) you can dive into the entire series of articles that Alexis had devoted to the subject here: Stratégies.

Strategy?

Strategy is a question of management, it’s a question of decision-making, it’s a question of risk-taking, and it’s the acceptance of uncertainty. The question we ask ourselves is: how do champions make decisions? We’re talking here about chess and go champions for example.

A strategy is adaptive

In these games we observe that every strategy is adaptive. Every strategy is a reaction to a situation. We don’t have a strategy in advance. We don’t calculate a strategy in advance contrary to what people believe. We have a vision of a direction, of an intent, we have a strategy that adapts to the situation, and an implementation tactic.

People imagine moreover that chess players calculate dozens or even hundreds of moves in advance. To this Alexis responded by quoting Richard Retti, a Hungarian chess champion from the 19th century, one of the best from 1910 to 1920, who said: “chess enthusiasts who ask me how many moves I calculate in advance when I make a combination are often very surprised when I answer in all honesty: my rule is to never calculate beyond one move”.

While searching for this quote I stumbled upon another that echoes it. It’s Samuel Reshevsky, another grandmaster between 1930 and 1970, who says “Young players calculate everything due to their inexperience”.

If I return to our product *ers, but I think they already know this, the posture is to accept uncertainty.

Garry Kasparov’s 5 steps

So how do we deal with this uncertainty? How do we deal with this application of strategy? Through decision-making. Alexis mentions five steps in Garry Kasparov’s reasoning (whom you’ve all normally heard of) that leads to making a strategic decision.

These five steps are:

- Identification of the key moment

- Position evaluation

- Situational analysis

- Risk exposure scenarios

- Decision

Identification of the key moment

It’s a key moment: a tipping point, an orientation, with no possible return. It’s a decision we won’t be able to take back. All of this emanates from a feeling, not from a calculation. We know we’re in a key moment, we don’t calculate it.

Position evaluation

On this, we use the dimensions used by the military domain: material dimension, spatial dimension, temporal dimension.

We could say regarding the product *er: The material dimension concerns our product, what do we already have? What technologies are we using? What’s the state of technical debt? Etc. The spatial dimension: where are we in the market vis-à-vis the competition? The temporal dimension: are we late or early?

This is quite calculatory as Alexis would say, and not based on a feeling.

Situational analysis:

In what system are we: we’ll come to this below, it’s a particular point.

Risk exposure scenarios

Based on the previous points, what are the risk exposure scenarios available to us. There’s uncertainty, there’s risk. If we already knew in advance, we’d play our move and that’s it. But no, that’s not the case, chess players talk about “fog”.

Decision

When we’ve seen all the previous points, we decide. It’s a frank and definitive act.

Back to situational analysis

Let’s return to our situational analysis. Alexis, at the head of his specialized publishing house, receives manuscripts from the champions we mention. At one point he receives two simultaneously, one from a great go champion, the other from a great chess champion, who hold completely opposite views.

In go, the champion explains that when behind (position evaluation), he attacks, he increases the risks. In chess, the champion explains that when behind he consolidates. Between the two it’s a total inversion! Why?

There’s a fundamental difference between go and chess. Go is a counting system: you count the points accumulated (or not). Chess is a sudden death system: you win when the king is taken, regardless of the state of the game otherwise. This explains the inversion in their response. But what about in the organization with product *ers?

Alexis makes the connection with the company’s cash flow. If the cash flow is not at risk, we’re in a counting system, if the cash flow is at risk and can suddenly signal the company’s demise, we’re in a sudden death system. I think this can be related to other things than cash flow. Notably more individually your career: if in the risks associated with building your product you damage your career without putting it in real danger, you’re in a counting system, if you’re putting your career at stake you’re in a sudden death system. To return to the idea of cash flow, I’ll use the term “absorb”, if the risk can be absorbed you’re in a counting system, if the risk cannot be absorbed, you’re in a sudden death system.

Strategy associated with a position of delay

And thus if you’re in a counting system (you can absorb the risk), and you’re behind, like the go player, it’s advisable to attack. A large company that’s behind and can absorb the risk should thus attack. What would attacking mean for a product *er? Try new ways of imagining their product? Try a new audience? Try a new partnership? Try a new image? Try a new type of…? We increase the risks.

Conversely if you’re in a sudden death system (the organization cannot absorb the risk), like the chess player, your priority is avoiding sudden death. You consolidate, you secure. For a product *er you ensure you deliver the most expected elements, the most foundational, deliver a foundation, the essential. We try to decrease the risks.

Mixed system

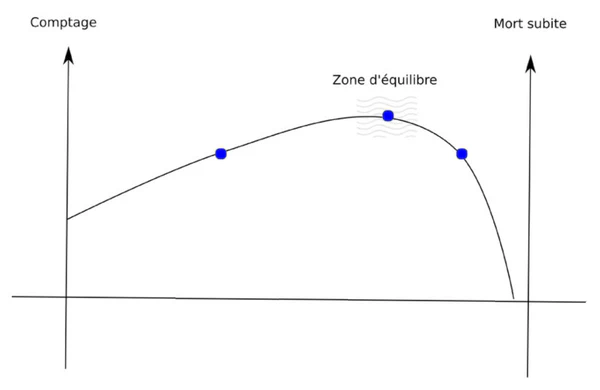

There’s very often a mixed system that starts with a counting system (we can absorb the cost), and ends with a sudden death system (we cannot absorb cost). Between the two, a zone of equilibrium.

A mixed system is a system that starts with a counting system (we increase risk), ends with a sudden death system (we limit risk as much as possible), and passes through a zone of equilibrium. Imagine a ping-pong game, now in 11 points, at the beginning you’re in a counting system, no drama losing points, so you can take risks, but at some point we arrive at a zone of equilibrium then we tip into sudden death, if you’re behind, at any moment you can definitively lose. No more question of opening up to risks.

For a product *er at the beginning of their product, at the beginning of their increment, at the beginning of the new phase around the product, they’re probably in a counting system, then comes a tipping point (zone of equilibrium) that makes them shift into sudden death system, now things must be assured, secured.

Value, impact and risk

But why take risks? Because with each risk is associated an increase in impact, in value. It’s the line in the middle of our diagram above. It represents the increase in chance of gain (value, impact) by increasing risk.

The good product *er will therefore know how to maximize this capacity to increase their chances of gain by using the right strategy at the right moment.

How to detect the tipping point?

Is it simple enough to know if we’re still in a counting system or if we’ve shifted to a sudden death system? At the time we proposed (I haven’t changed my mind) to shift slightly in time to perceive where we stand. We vary a parameter to better feel where we are vis-à-vis equilibrium. For example I’m working on a product and I’m hesitating to launch into a new approach on a new use case. If I’m in a counting system, might as well do it. But am I still there? Isn’t event E associated with the product too close? To feel it I project myself in time, I try this new use case (I take this risk), and ultimately it doesn’t work, do I find myself in an acceptable situation (no sudden death)? Yes? I’m still in a counting system (I can increase my risks). No! I’ve actually already shifted to a sudden death system (I must limit my risks). I don’t know! I’m right in the zone of equilibrium, and there, bad news, there’s no answer.

Agility and risk management

In my eyes agility defends itself as a risk management system. For example as I detail in La disparition. In this framework too – strategy – agility proves itself. Its end-to-end approach, straight to the goal, maximization of value while minimizing effort, its work on emergence, is a way to optimize our capacity to take risks (by mitigating them). The risks will be much less painful and we can take many more. We thus increase our chance of gain (value, impact). Agility maximizes the counting system, and pushes back the sudden death system.

Temperament

Alexis ended our conversation by mentioning the temperament necessary for the product *er. Temperament is needed to open up to risks, go as far as possible, without going too far (all of this is also very close to real options, and the last responsible moment from lean).

Today I would associate this notion of temperament with Skin in the game by Nassim Nicolas Taleb. We’ll feel the passage from counting to sudden death, we’ll have the temperament to advance risk-taking until the last responsible moment if and only if we’re committed, if and only if we’re putting our skin in the game, otherwise sudden death makes no sense, and we’ll remain in the fog.