I’m living through a strange year, an airlock, a transition. I’m taking advantage of it to consolidate my writings, assemble things, and soon propose a small book, among other things.

This small book could be addressed to all sorts of leaders, but also and especially to my (already grown) children. To pass on to them in a certain way this knowledge and experience, so they can benefit from it in the great upheaval that’s coming (or that has already begun). For this, I imagine an ecovillage in 2052, let’s say about twenty years after the official collapse of civilization as we know it, a collapse linked to humanity’s impact on planetary boundaries, and the necessary complete readaptation of our lives. In 2052 my grown children, Sarah and Mathieu, will be the age I am today as I write, my youngest, Arthur, will be at the dawn of his forties, almost like Sibylle, my partner’s daughter, whom I include in this small group I cherish.

They’re part of an ecovillage. The collapse of our civilization (for a better one I hope) gradually occurred, but it’s in 2034 that the tipping point is officially dated. A group of resistance fighters, the Carbon Squad1, sabotaged the World Cup in Saudi Arabia. But I’ll tell you about all that over the coming days.

I’m proposing here a “section,” a “draft,” of this small book, the one on decision-making and organizing in circles. So you’re in an ecovillage in 2052. But my examples can very well adapt to your organization today…

In this hypothetical ecovillage, who decides? About what?

I can tell you that observing who decides, and where it’s decided says a lot about the organization. Are all decisions centralized in one place? Are they on the contrary distributed everywhere and if so how does this work for decisions that impact everyone? Are decisions even being made? And how are decisions made?

We must clearly distinguish the question who makes this decision from the question how we decide.

I would still say that who makes this decision is the most important. It’s structural enough to then answer the how.

I propose going straight to the answer that seems most relevant to me: the best decisions are made by those who are impacted by said decision. Let’s quickly put this proposal into practice:

- If a decision impacts your entire ecovillage, I imagine it should be made by the entire ecovillage.

- If a decision impacts the whole team, or all the people who make wheat and bread, I imagine it’s up to the whole team, or all the people who make wheat and bread to make it.

- If a decision impacts Arthur’s family, I imagine it’s up to Arthur’s family to make this decision. But if it impacts three families, I imagine it’s up to the three families to make this decision.

It’s quite simple. Except in the case of fairly global strategic decisions. For example “Do we want to trigger cooperation with the three neighboring villages?” Is it the whole village that’s impacted and must decide? Or is it your village’s governance team — if there is one — that’s impacted (it will have to answer for it, it will have to implement this decision, etc.)? Basically, do strategic decisions belong to a sort of “management,” a global governance group? I don’t have a definitive answer.

This question of impact also frames the spectrum, the room for maneuver of the decision. If Arthur’s family makes a decision that impacts other families, part of the village, this extends de facto the group of people who should make this decision.

Several authors or movements of thought have described this idea that the best thing was to have things decided where these things take place, by the people they impact. Authors like Nassim Taleb2, or like Taiicho Ohno3 notably, but also the sociocratic movement4. What do they all say in their own ways?

- If you make decisions that don’t impact you, you make bad decisions. If we don’t risk something in the decision, the reasoning is flawed. It’s those who suffer the risk who know.

- Decisions are made in the place where the need appears. It’s in the middle of the subject, immersed in the context, that we know most relevantly the right answer to provide. It’s those who do who know in a way.

To this, I add that if you let those who do decide:

- You nurture their need for a sense of control, mastery of their environment, which will engage them, and in a virtuous circle, will make these decisions even better decisions.

- If these decisions turn out to be bad: it will be all the easier to stop them, and the learning will be much better (conversely, stopping a decision that we undergo is more complicated and applying a bad decision doesn’t teach much).

- You don’t take risks by letting the right people decide if the framework of the decision is well delimited, and if as we’ve seen (in many previous articles) we work on small pieces.

Conversely:

- Making decisions that won’t impact us puts our judgment at risk.

- Making decisions about how others must precisely accomplish things is to make them irresponsible, to disengage them.

You could divide into four types of people those around your decisions (let’s take as an example decisions around making our bread, and this search for food autonomy linked to the ecovillage):

- Those who have strong expertise on the subject: for example those who are experts in bread-making.

- Those who will eat the bread.

- Those who will make the bread.

- Those who will neither eat nor make the bread, and who aren’t experts.

You understand that it’s those who will eat and will make the bread who are most able to make decisions about what bread we make, with what flours? And how we make it.

But this probably requires expertise (remember the complicated domain), and we’ll need to rely on experts. If the experts are part of the manufacturing team, great, they participate in the decision. If the experts are neither part of the manufacturing team nor eat bread, we consult them, but the experts don’t decide. At least that’s what I advise. We understand in any case that the decision involves accountability: if those who make and eat the bread don’t want to listen to the experts: they take responsibility for it.

But the worst is avoided, the worst that we unfortunately observe far too often these days, the worst is when those who will neither eat nor make the bread make all the decisions about bread.

Be careful making a decision is not imposing a constraint, it’s not setting a framework.

Let’s imagine I’m the grand steward of your ecovillage (yes yes let’s imagine this role exists), I can impose a constraint on the “Bread-making” group by telling them, for example, “this must not take you more than two hours of work per day and not encroach on our already cultivable lands.” There I’m not deciding anything, I’m framing, I’m imposing constraints. I’m the grand steward: I manage risks, and thus I limit them.

But I leave the decisions of the manufacturing itself to the group. And as a group, we’ll need to decide what bread we want and can eat.

For several decades, there has developed from France and Holland a movement called sociocracy that proposes an effective system for distributing decisions to the right level, the right place.

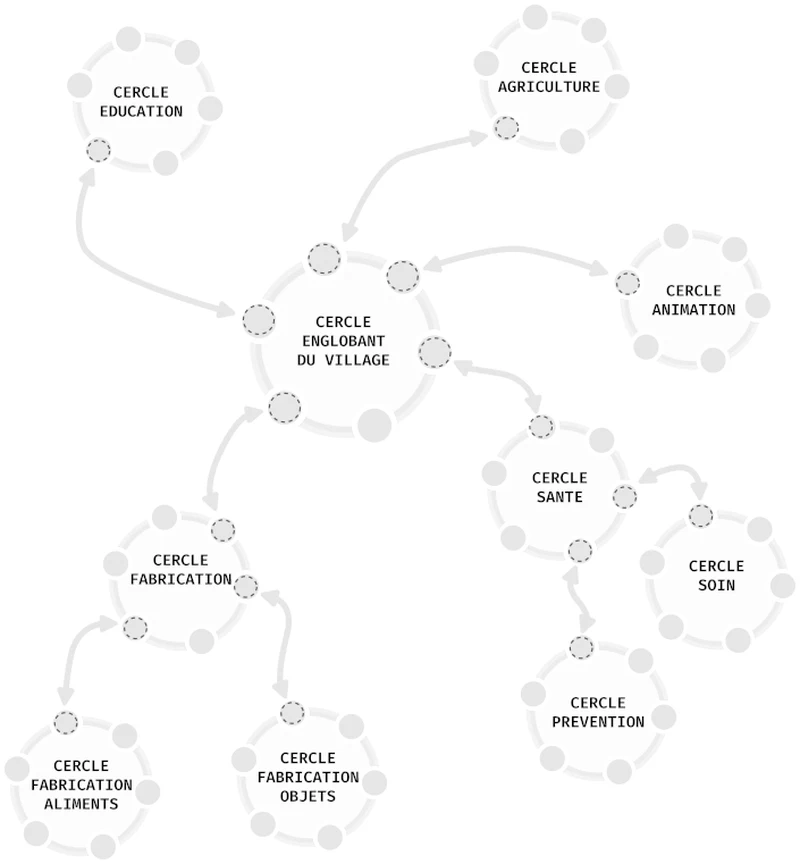

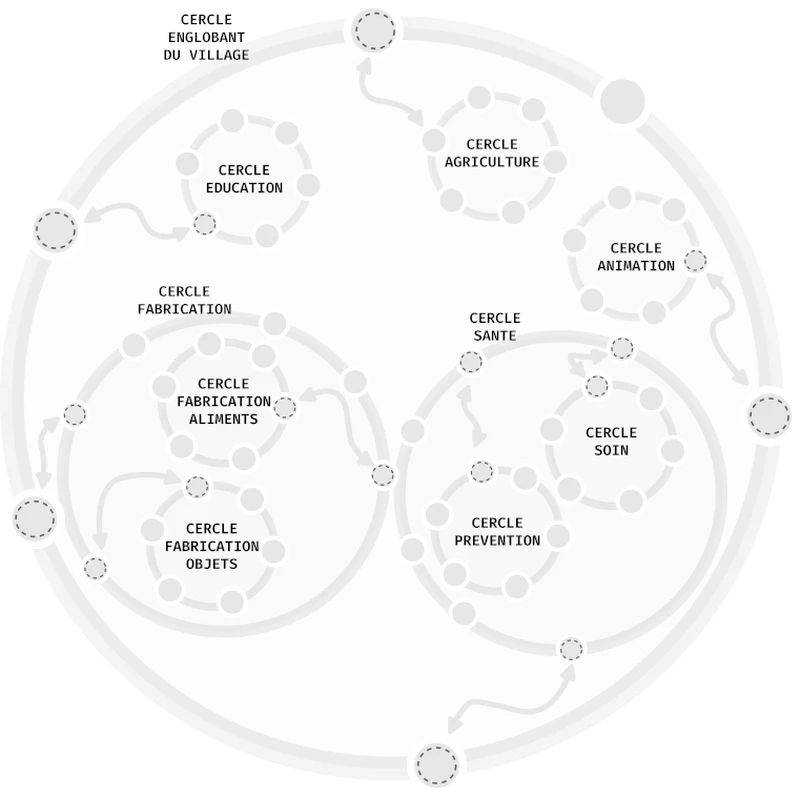

Imagine that your village is a large whole, in sociocracy we’d say a large circle. There’s then a large village circle. It itself breaks down into several sub-circles: the manufacturing circle (objects, raw materials, food, etc.), the agriculture circle, the exchange and relations with other villages circle, the education circle, the care and good health circle, the entertainment and festivities circle, etc.

Good distribution of decision-making is that decisions about education are made in the education circle. And therefore, decisions about bread-making in the manufacturing circle.

Each of these circles also probably has sub-circles that themselves also perhaps have sub-circles. We can easily imagine that the manufacturing circle breaks down into sub-circles object manufacturing, raw materials manufacturing, food manufacturing, etc. These themselves therefore potentially break down into other sub-circles.

We create a circle when we need it, when it makes sense, when there’s a reason. When the ecovillage was very small, a manufacturing circle was enough. Now that it has grown, it’s composed of more specialized sub-circles (like for example food manufacturing), it became necessary to accomplish things.

We can also create very temporary circles that organize more around specific projects than recurring needs. For example, the circle for building the new bridge over the river. When it’s finished, the circle is dissolved. If a circle no longer has a reason to exist, it must be dissolved.

What is a circle? It’s a group of people to think, do and decide on a subject. And as we’ve seen, a group appears at four people (but three works very well for me too), and it works well up to seven, eight people maximum, so these are groups of four to eight people. But this group can represent a larger number of people. So we could have our food manufacturing circle of four to eight people, who represent a team of twenty people. And probably moreover these twenty people are organized in circles that are sub-circles of the food manufacturing circle.

Who composes the circles? The people concerned. Generally experts on the subject, and people who will be impacted by the circle’s objective. However, there are no strict rules. Having those who want to be there is good too (it’s an invitation).

But don’t circles cause dispersion and disparity that generates complexity? Is it possible that many sub-circles of the manufacturing circle make antagonistic, opposing decisions?

No, because another mechanism comes into play: in each circle there’s a representative of the superior circle whose role is to frame, to impose constraints linked to overall coherence. We need to go back to the beginning of the story to understand the mechanism. Your ecovillage starts small, you’re a group and you decide everything for yourselves. Then as you grow, certain circles form agriculture, education, etc. You need them. The reason for being of the education circle is “to ensure that each member of the ecovillage accesses knowledge to be free.” You talked about it with your initial group when the need became such that creating this circle became obvious. You also probably defined in a bit more detail what you expected from this circle, and one of you somehow took the lead. The expression is unfortunate, because by taking the lead we imagine that you became its boss or chief. Unfortunate, because you won’t give orders (what we associate far too often with “chief”). But chief in the sense that you’ll be the guarantor of the framework. You carry the circle’s reason for being. If people in this circle start discussing everything except education, you reframe. You also potentially bring constraints like we mentioned with bread-making (“no more than two hours of work per day, don’t use already cultivated lands”).

And each time a sub-circle is created, a member of the superior circle is brought into it as guarantor of the framework and constraints. These people therefore participate in two circles that are thus linked together, through them. This mesh ensures coherence and information diffusion. And moreover when we’re stuck in a circle on a decision we can raise this decision to the circle above.

So a circle is indeed created when it’s a need, when it makes sense. It’s created with a reason for being, and a list of things expected from this circle, even a list of constraints. The circle exists if it’s composed of four to eight people. Each circle has a particular person who connects it to the superior circle, except for the first encompassing circle.

Should we imagine there’s a large village circle? Not really, but there’s a large circle encompassing all the other circles that’s composed of village representatives (either original members, or elected officials, or something else). It’s the first circle, the initial circle.

Incomplete example of organization in circles

Incomplete example of organization in circles, another way to represent it

Both diagrams represent the same thing, in two different ways, it’s up to you to grasp the one that suits you best.

Circles have the effect of everything we’re looking for:

- Decisions distributed to the right places: those who build the bridge over the river decide about it (but the decision to build the bridge was probably made in a “superior” circle), those who make bread decide about it.

- This engages actors who control their environments.

- Circles give meaning. They’re defined by a need, a reason for being, and disappear if it disappears. This meaning engages people.

- A framework, expectations and constraints: in return, this allows a space of freedom and responsibility.

- Overall coherence, because each circle is linked to its superior circle.

This is indeed a hierarchy, but a hierarchy of decision-making. The major strategic directions are decided in the village encompassing circle, decisions on the broad meshes of manufacturing things in the manufacturing circle, decisions more precisely on food manufacturing in the circle of that name, etc. The representative of the village encompassing circle is guarantor of the reason for being and framework of the manufacturing circle, and itself has a member who becomes the guarantor of the reason for being and framework of the food manufacturing circle, etc.

To conclude: the best people to make decisions are those who take the risks of the decision’s consequences. We must not confuse deciding and framing, nor deciding or constraining (putting a constraint). The best would be to project the role of “bosses” into framing or limiting roles (and beware too many constraints suffocate), and the role of others is to decide and do. “Bosses” decide when it concerns them: generally strategy, sovereign decisions, etc.

-

It’s Henri Loevenbruck who launched the “Carbon Squad” scenario and the idea of making a role-playing game around “post-collapse.” I joined him to build with the carbs the module for Foundry (basically an online role-playing game platform). We talk a lot about this “Carbon Squad,” it’s his baby, but I’m taking the liberty of using it (with his agreement), and proposing a personalized branch. His site: https://henriloevenbruck.com/, also look for him on YouTube (or via invidious even better) with the name DrakenRPG. ↩︎

-

“Skin in the game (Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life)”, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, 2018 ↩︎

-

“The Machine That Changed the World”, James P. Womack, Daniel T. Jones and Daniel Roos, 1990 ↩︎

-

Wikipedia Sociocracy: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sociocratie ↩︎