The roundtable or open conversation that we initiated with Tristan in the last episode of frugarilla [August 2023] had as its starting point the notion of tipping point between a community involved in a subject: our eco-responsibility, and public opinion, how and when a shift occurs to spread and win people over to a cause. The freedom of the conversation led us to many interesting subjects, without necessarily answering this starting point.

For my part, I was making the connection with a famous book, often used in the world of lean startup, called crossing the chasm by Geoffrey Moore. Admittedly the book is dated (1991), but the edition I’m holding in my hands is – itself – from 2014 and I think an update took place.

Why make this connection? Because this book, for another subject (California startups to keep it short), addresses the same problem: provoking a shift in opinion to spread – en masse – one’s product, service, convictions. And even if it wasn’t at all intended as a reflection on eco-responsibility, it seems to me that it brings us interesting leads.

The fact is that we observe an invisible wall between the majority of people who, even if they care about eco-responsibility and our future, don’t change their ways of living and thinking about the world, and a minority who do change their way of living and thinking about the world. An invisible wall, because the first group seems deaf to the requests, the desire, the messages of the second group.

This is an important debate around eco-responsibility and the future of the planet.

What could this book teach us?

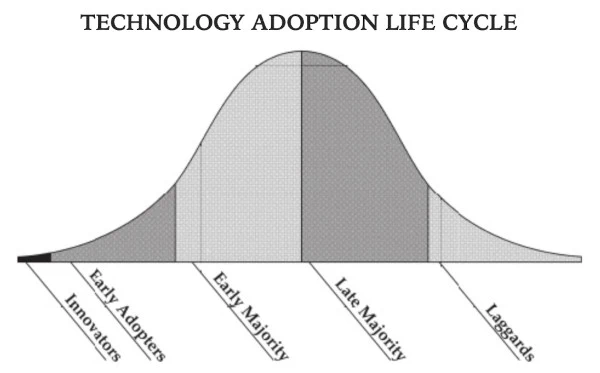

This book is based on the notion of the Technology Adoption Life Cycle. This cycle and this adoption are based on a diagram, a curve, “a bell.”

And I observe that the difficulty we face in getting the subject of the environment, of the planet, to be truly taken in hand by the vast majority, the difficulty in convincing, explaining, getting messages across, runs into the same problem as that of a technological product as developed in this book. We could thus also draw inspiration from the leads it proposes to bridge this gap.

So here several families of people that a product gradually conquers (if it’s successful).

The innovators: the enthusiasts, they try everything before everyone else. They love the new.

The early adopters: the visionaries, the agents of change, they have convictions on the subject, they seize it.

The early majority: the first big chunk of majority (of massification), Geoffrey Moore calls them the pragmatists, this is important, we’ll come back to it.

The late majority: the other piece of the majority that comes after, Geoffrey Moore calls them the conservatives.

The laggards: the stragglers, he calls them the skeptics. Those whom we call, not by chance, concerning our subject, climate skeptics.

The electric car test

Since we’re talking about chance: when he writes this book, he takes the electric car as an example to position people in these different groups by questioning them on this theme. At the time it’s still a very uncertain technology. So uncertain that his question starts with: “Imagine that these cars work like any other (sic)[author’s note], and that on top of that they’re good for the environment,” – and he concludes – “Would you be ready to buy one?”1

- If the answer is “Not until hell freezes over!”2 (comical when you know what’s happening today…), you’re probably a skeptic.

- If your answer is: “When I’ve seen electric cars prove themselves and when there are enough service stations on the roads”3, you’re probably a pragmatist.

- If you answer: “Not until most people have switched and it becomes really inconvenient to drive a gasoline car”4, you’re probably a conservative.

- But if you want to be among the first people to want an electric car – at that time – because you love novelty or you want to support the environment, you’re certainly either an enthusiast or a visionary.

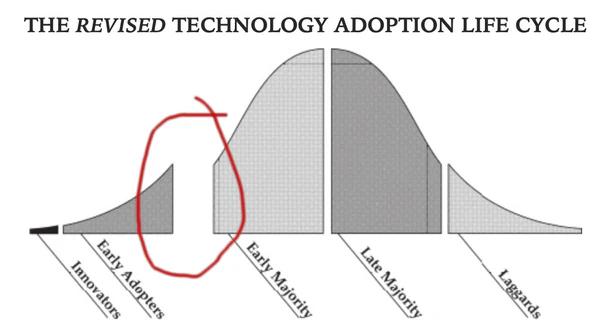

And then? Where is this gap to cross?

There’s the gap. This place is the hardest to cross. Between the small group of agents of change, of visionaries, and that of the pragmatists. And it’s exactly this gap – it seems to me – that we must cross: frugarilla of which I’m a part or other “activists,” or “committed people,” and in which it seems that all our efforts get bogged down.

This “bell,” this “curve,” implies the idea that it advances from one stage to another: enthusiasts seize an idea, visionaries nourish it with meaning, pragmatists then take the subject in hand, conservatives are then won over, and finally even skeptics perhaps give in. But the diagram also indicates that the passage from early adopters (agents of change) to early majority is the hardest, that it’s often a place of failure for new technologies seeking to sell themselves. But why do our efforts get bogged down in this gap?

Because the agents of change want change based on convictions, BUT the pragmatists want “a productivity improvement, and to minimize the discontinuity with the old world”5. It’s the exact opposite! And we also know that they won’t launch without an example from their community, but no one wants to go first: we’re at an impasse.

So two difficulties:

- The expectations of the early majority are contrary to the expectations of the early adopters. The two expectations are opposite and you don’t respond with the arguments of the first group to the second. Otherwise, on the contrary, probably, they dig in their heels.

- This majority will only be convinced if other people in their group are convinced: but no one wants to take a first step. Everyone’s holding each other by the goatee. These pragmatists often lack a reference base of people like them for whom it works.

What response leads does this offer us?

First, understand that responding to their concerns with the answers to our concerns probably doesn’t work.

On the other hand, we need to find people who reassure the pragmatists, people from their clans, their circles. What the book offers you, using the metaphor of the D-Day landing on June 6, 1944, is to find a beach to land on. Meaning to find a target, small enough, on which we can gain a foothold.

For example, today I don’t see anywhere in companies where the idea that growth is opposed to the environment and that growth is necessary is challenged. The book’s proposal is not to use our arguments to convince, but to find a niche, a beach, a set of professions, companies where success could no longer equate to an idea of growth, but to a virtuous system, in harmony, integrated with the planet. Find the right place, normally small, but which shows that it works. The pragmatists need to see that it works, that it’s possible.

From the moment a niche, a market is won over to this new idea, and it works: the niche lives, prospers (but not in the growth sense), the other pragmatists will be ready to take the plunge.

And so Geoffrey Moore’s advice is to carefully consider which beach to land on. Which market is the right market to change these rules of the game that we’d like to see change. Which market is the right Normandy beach to demonstrate a new way of seeing the company or the system?

This is a reflection that I propose you launch.

ps: it’s the same issue with these famous agile transformations: the expectations of middle-management, of pragmatists or conservatives generally, are opposed to the expectations of early adopters, of agents of change. And we crash when responding to both in the same way.

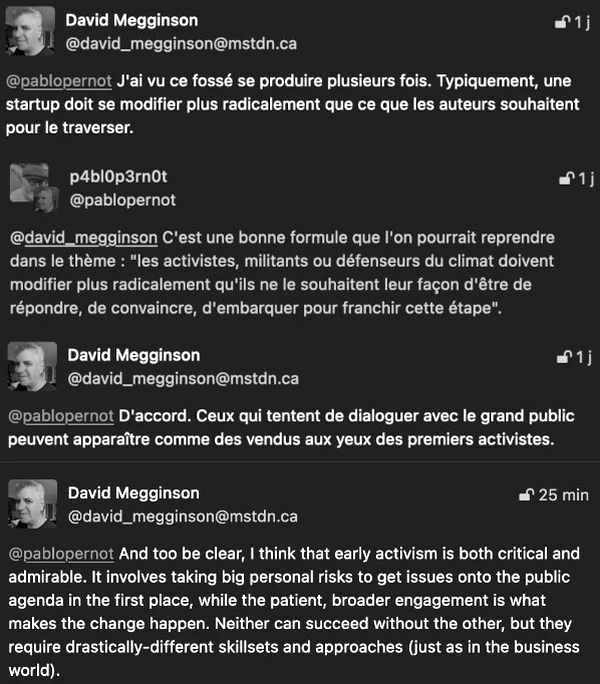

supplement (conversation on mastodon)

-

Stepping back a bit from the cool factor, let’s assume these cars work like any other, except they are quieter and better for the environment. Now the question is: When are you going to buy one? ↩︎

-

Not until hell freezes over. ↩︎

-

When I have seen electric cars prove themselves and when there are enough service stations on the road ↩︎

-

Not until most people have made the switch and it becomes really inconvenient to drive a gasoline car ↩︎

-

Productivity improvement, minimise the discontintuity with the old days. ↩︎