Today is yesterday, we can feel it clearly. We’re living in the world of before. We’ve been talking about “Great resignation” recently, but I have more the impression of “The great realization,” in the sense that everyone, myself first (or last), seems to realize the importance of our eco-responsibility. For a digital product actor, the paradox is painful—everything in our world revolves around technology, nothing about technology seems to align with the world. And yet products shape our world. The question of eco-responsible products is therefore crucial. The good news? Emergence, complex thinking, systemic approach are the tools that allow us, today, to move forward on resolving our ecological problem. And we are trained in this way of thinking.

Before (in a future article) outlining the lines of reflection that occupy me regarding eco-responsible products, I’m trying to trace what has been key in recent years in my eyes. Why? To know where I come from, to better know where I want to go. Thus, before questioning the product of tomorrow, three perspectives: disruption, experience, and value.

I place the period of before, that of yesterday and unfortunately still that of today, from the late 90s until now. Why the late 90s? We shifted into another world. It’s probably linked to the spread of the internet that made us enter another period, another type of industry, another type of company, another type of innovation, another way of working. It also coincides unsurprisingly with those famous agile approaches.

From this period we can’t retain everything and I’m going to focus on the two things that seem significant to me. Two phenomena. The first is disruption, the second is experience.

Disruption

What is disruption? It’s from all times, when Ford proposes a car versus a horse, it’s a disruption, a change, a rupture. Same when Fosbury does his high jump. There’s a book that made quite a stir at the end of the 90s (precisely), by Christensen, which was called: “The Innovator’s Dilemma” (facing disruption). What is this innovator’s dilemma facing disruption? We could understand it as a fear. We’ve talked a lot about Kodak, Yahoo, lots of quite symbolic brands that have been “disrupted” as we say. We also talk about disruption with complete paradigm shifts in markets, uberization is a form of disruption. We suddenly lose a market, there’s a rupture in usage patterns, Uber, AirBNB. Thus “disruption” frightens as much as it excites.

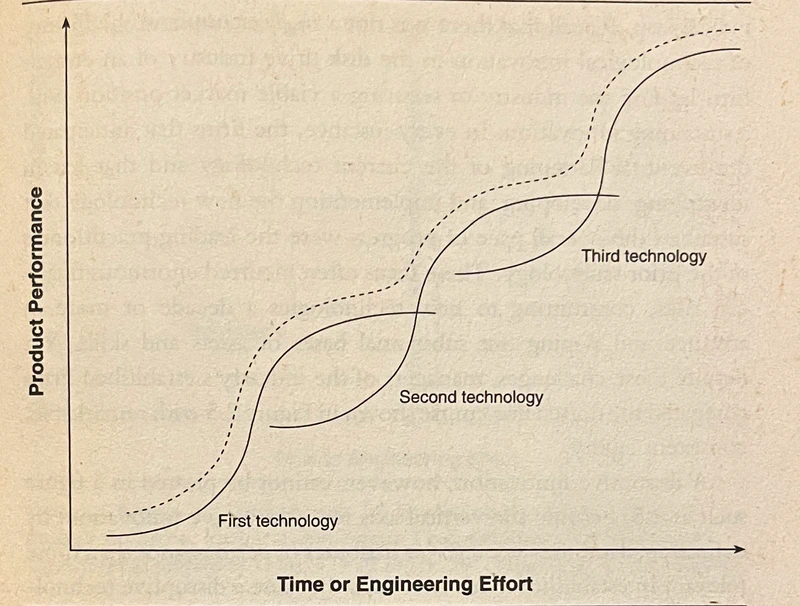

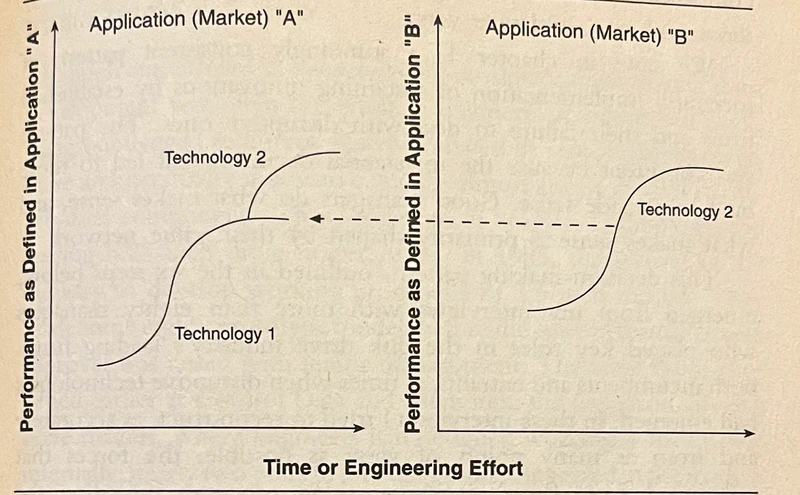

But dilemma? What would it be? First point, Christensen explains to us, when you have a product it experiences an S-curve. It starts slowly while you find your market, and then it accelerates, then you’re in growth, you’re powerful, then at the end we find the curve of the S that brings you back to a plateau. This product will have given what it had to give. And thus the expected effort in product management occurs at the moment of this full power: you must think about triggering a product renewal, a product relaunch with a new version, improvements, changes, which means that when you’re going to reach the flat zone of this product version, the end of growth, you’re going to have the next version arriving. It will have started slowly in the shadow of the previous version, and it will be at full speed when the first one runs out. And so you chain versions with constant improvement of your product, and you continue to surf on full power. This is what we seek (in the world of yesterday and today). With all this we maintain our market, we’re good with our market. But we’re also hypnotized by our market: when we’re at full power, with so much expectation, it’s hard to look elsewhere.

When you’re feeding this market with your product, you’re not feeding tomorrow’s future market, thinking about tomorrow’s product. And while you’re hypnotized by your installed base, by your power, by the fact of enriching your product (and yourself at the same time), there are small companies nearby creating niches with a completely different approach. And when their niches grow and in turn gain power, they can cause a rupture in the market and suddenly make you obsolete. No matter how you’ve enriched and maintained your product.

And thus the dilemma appears: should I vivify, enrich my product, or should I forget it, and prepare other products that will be at full power later, but which today perhaps have no connection with either my customer base or my image. The dilemma of working with your enormous installed base, or taking interest in the few early adopters of a new product.

(Note that this problem already seems very linked to our questions about tomorrow’s products).

Grow and make my product prosper, or project myself onto a rupture. You could do both.

You could have acquisition policies. You could buy companies that have taken the time to build a market on completely disruptive products for which I wasn’t prepared and which transforms my market without resembling my product. But buying isn’t so simple, and it’s prohibited by law precisely to leave room for innovation (American antitrust law for example). As a reminder, Zuckerberg saying “I’m buying myself time by buying Instagram” (Listen: “Can we still believe in the benefits of innovation - Radio France”).

And buying doesn’t train your reinvention muscle at all. Because you’ve grasped that on one side we’re talking about renewal, on the other about reinvention. The dilemma is the temptation to simply renew yourself because you keep your position, your power. Reinventing yourself is so much more destabilizing.

These ruptures, these disruptions, we’ve observed them quite a bit in these years of great complexity, the famous VUCA era. And also because technologies, through the power of technology, put many markets back in play. There are very few non-technological disruptions, and any actor who doesn’t think technology takes the risk of being excluded from their market. This is one of Marty Cagan’s mojos in “Empowered”: “No product disruption without technological disruption.”

The Experience Economy

Another perspective: the experience economy, the “experiential” product.

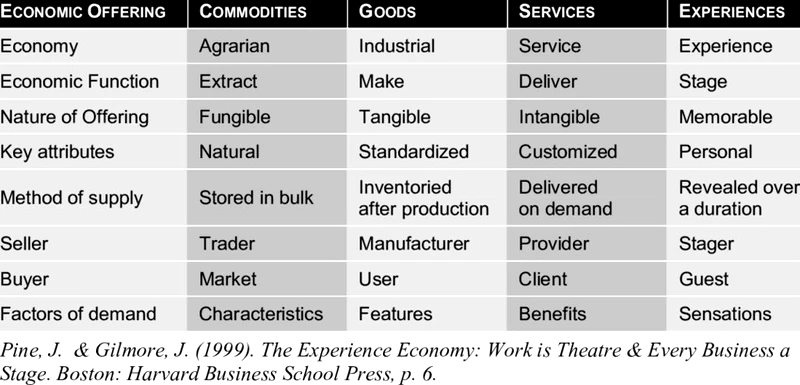

Here too there’s a kind of foundational text at the end of the 90s (just like this agility that also emerges there), on the experience economy. The experience economy is a notion highlighted by James Gilmore, which tells us that today the most powerful products are experiences. See: Welcome to the experience economy, James Gilmore

He gives a very simple example: before you bought strawberries to make your cake, it didn’t cost much, you bought strawberries and flour then you made your cake. And then later you instead bought the cake directly from the bakery, it costs you more, but it’s more practical and over time people bought cakes rather than making them themselves. All this is for your children’s birthday. And then came the service. You had the cake delivered on the birthday, during the birthday. It costs more, but it’s even more practical. And then there’s a kind of entertainment, sensations, emotions that come in addition to that, which is that you want to live an experience and rather than having the birthday at your home you take the children to a place made for birthdays in which there’s a clown, there are games, there’s music, there are dances, there are activities, there’s a cake, but the cake is far from being the most important thing, and it costs much more. And all the children will demand your product, this experience.

Why are many companies fond of experience, because suddenly we shift to a relationship that is much stronger, much denser with the customer who we then call a guest. It’s them who comes, their emotions, their sensitivity, which goes with it is theirs. And thus their memorization is much better, and thus the guest comes back much more often, they’re much better retained. Service becomes a commodity, commodities don’t capture.

“Companies must create memorable situations for their customers, and experience is an attempt to build dense relationships with them” Jean-Louis Frechin (“The Design of Things in the Digital Age”) tells us.

IBM’s slogan was “IBM means service,” McDonald’s was “Come as you are.”

In music, before I bought a record, after I had a streaming service, and then I could say I go to a concert. Besides, today music costs nothing, by subscribing for 15 euros per month I have all the records on earth, and the record no longer exists (we’ll talk about vinyls after). But if I go to a Bruce Springsteen concert like there will be one in Paris, the worst seat is 170 euros, a year of online music, and the best seat is 720 euros, five to six years of online music. Why? Through experience, it’s mine I’m there, it’s unique, memorable. But if I had to make my online music streaming tool experiential? Two ways Gilmore tells us: participation and connection. With whom do I share my music, what music is suggested to me and to me alone because it’s my tastes. I come back to vinyl, because now a record sells for more than a month of online music. But because it’s a private community to which you belong. You’re willing to degrade certain aspects of music (turn the record every twenty minutes) because it involves physical sensations, the hand, a kind of sensual moment like the tea ceremony, and belonging to a caste of knowers, those who know where the sound is best. Same with 3D sound in the ears. So the price you put (and that’s also the impact of personalized experience) says things about you. I’m paying for music that resembles me. I left Spotify for Tidal to follow Neil Young. We’re in emotion, in memorization, in convictions. With Tidal I pay artists better they tell me.

Here too technologies play a fundamental role. Before we made objects. Then, with industry we manufactured them in series, then with digital we managed to clone them identically, so more than in series, identically, to finally with this internet of things we reach a kind of ubiquity, multi-channel, it’s everywhere (Here too read “Jean-Louis Frechin, The Design of Things in the Digital Age”). It completely changes our usage patterns, hence the idea that the vast majority of disruptions are technological, and it allows for a reinforced experience, it’s around us, we’re in the middle, guest.

Conclusion

To these two phenomena, you can add the importance of value focus.

Because we quickly realized that to go fast, you must not go fast, but go straight to the point.

To go straight to the point, we asked ourselves why we do things, what we wanted, what we were looking for.

And then finally in a virtuous way when we asked ourselves what we really wanted, what value we desired, the first obvious solutions appeared as erroneous precipitations. By asking ourselves what we wanted we discovered that we had powerful ideas on how to get there in a totally unexpected way.

Thus came a whole work on maximizing value and minimizing effort. And with it, work on breaking down, accelerating cycles between hypothesis and validation.

But here we are, all this is the world of before, of yesterday and unfortunately still of today.

To make tomorrow today, it seems obvious to everyone that things must change. But we’re in a consumer society. A consumer society that I know very well how to profit from. However I’m not deaf and blind. Products shape our lives, to use an expression from Jean-Louis Frechin. And consequently it seems obvious that we’re going to have to change our products.