A few days ago I conducted a new retrospective with “benexters” at their clients’ sites. It’s an opportunity to have a fresh perspective with hindsight (and experience) to support them in their activities. Several topics emerged. And notably something that made me quickly say to them: no release plan? Well no, no release plan. It’s unfortunate and common. This tool is highly effective for communicating, harmonizing points of view, revealing contradictions or needs, facilitating decision-making, etc. In short, it’s a central element of product or project support. And it is too often forgotten.

It’s simple, and very effective, and a few small details seem crucial to me.

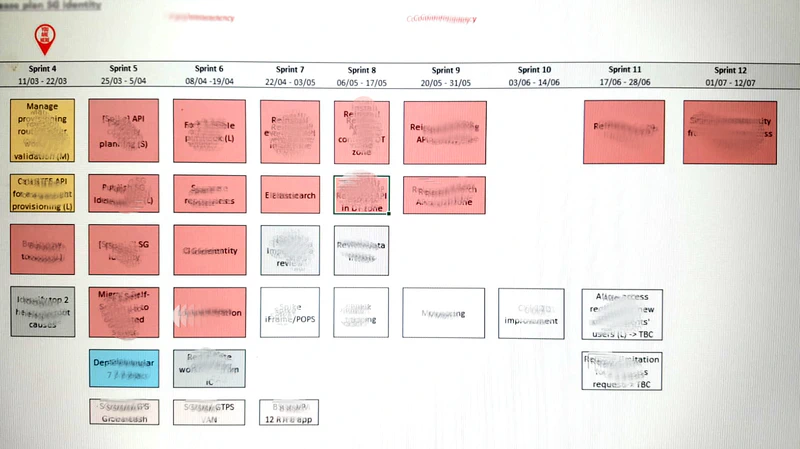

I’ll offer you a few telling examples (but always imperfect, “that’s real life”) that I’ll comment on a bit. The rest should be self-explanatory. (The content is blurred for obvious reasons).

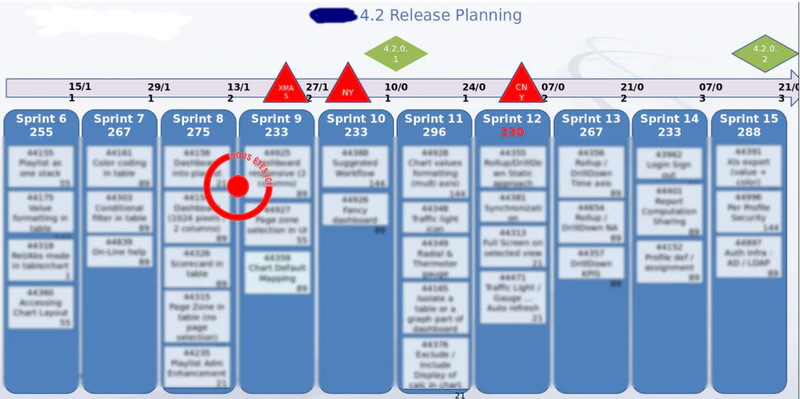

Example 1

A 3-month plan. It could be 6 months or even 1 or 2 years (but as time goes on, the blocks would become bigger and bigger, because increasingly approximate).

An indicator that tells us where we are. You are here. What’s before, on the left, is done, finished, ideally in production. We observe a validated, confirmed cadence (unless you say it’s done only to discover it’s not, hence also the value of putting it into production). And, on the right, we project. Estimates, ideally based on what’s on the left (we reproduce a cadence).

On the right, what is estimated? a) estimates are always wrong so b) the plan is constantly updated (a part on the left that shows the actual cadence, on the right the projection: sometimes it’s coherent, sometimes it’s nonsense to please someone).

In the boxes, the content of each iteration. Here the title is blurred, but it’s something short and meaningful to all stakeholders. The boxes represent capacity and they are in fact very important. This has nothing to do with a gantt.

The red triangles? Here, events, in this context: Christmas, New Year’s Day and Chinese New Year, which impact the teams. This should impact the content of the iterations, not the case here, we must be in denial. In any case, it’s important to show key moments on the release plan.

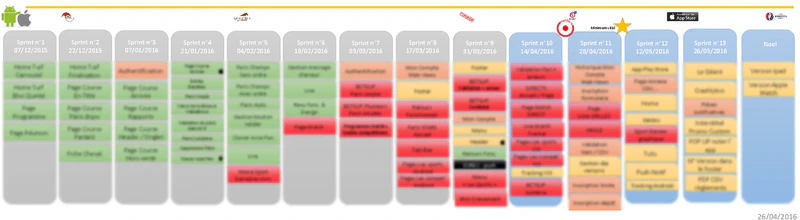

Example 2

Here the gray boxes (time passed), the colored ones (projection).

We also categorized user stories or features by colors. Imagine what suits you. Here it was horse racing betting in one color, sports betting in another, and finally customer relations in another.

Again the markers above: deadline for legal certification, date of the European football cup, but we also indicate with the yellow star from when we can release the product, even if it means not doing the last boxes.

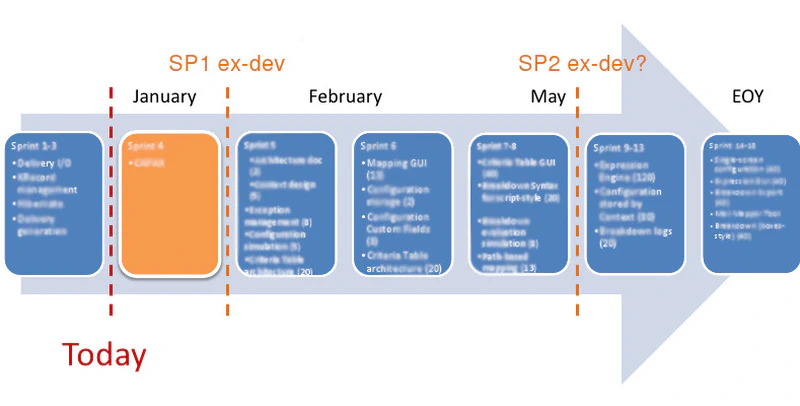

Example 3

In this example I want to show the inclusion of an iteration on legacy code, on another topic, suddenly, in the middle. This shifts the boxes or the content of the boxes. The capacity doesn’t change. Hence the importance of boxes, and not a layered gantt-type approach.

Verticality for reading seems important to me.

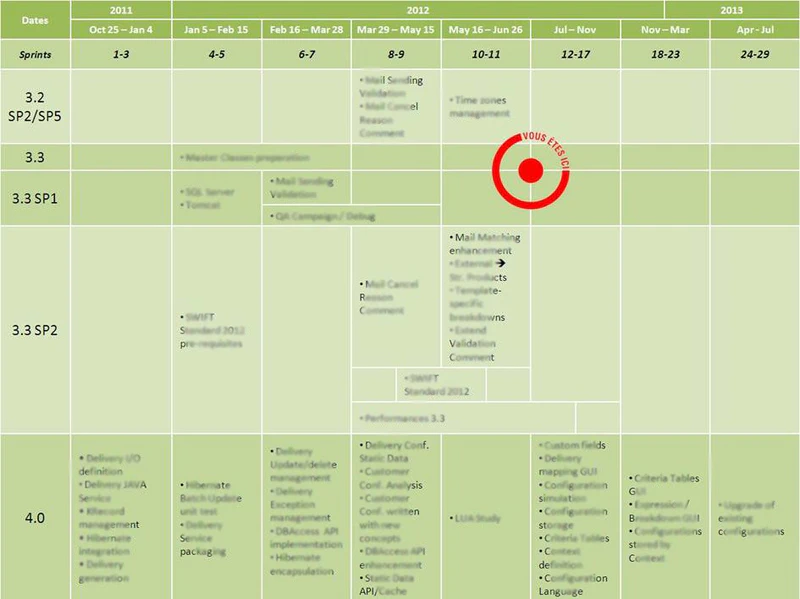

Example 4

This example is fictitious. It allows me to show you how you can aggregate several release plans into one to see the dependencies.

Example 5

This is a team that was working on five different versions of its product in parallel. But it could also have been five teams working in parallel to join the example above.

Did you notice that this spans two or three years?

Example 6

A last example: 4-month projection, no past yet, unfortunate; color codes.

A logical (and royal) continuation

Release plans are the final elements of a classic journey. A classic journey? Not all options are essential, but for example: a lean canvas for the need, then an impact mapping for the strategy, then a user story mapping for the implementation tactics, and perhaps an extreme quotation for “estimates”.

Who does it and when?

The product owner, the project manager, is responsible for it (they can delegate, I suppose, they manage).

The update is regular: at each iteration. This doesn’t mean major upheavals, just an update if needed.

Conclusion

We share it with all stakeholders. Release plans created this way can stress decision-makers who understand very well (they are never stupid) that if they add something the rest shifts. But it’s an honest view of the current situation. They perceive the variability of their requests if it exists. Everyone perceives the cadence, because it appears to everyone’s eyes. The release plan is therefore a highly political element in the good sense of the term, which concerns the citizen of the city, the actors or stakeholders of the product, of the project.

Addendum following publication

I hear: “we synchronize with 17 teams (…) even if it’s useful after a week it becomes wrong”. Careful, my experience makes me think that beyond 5 or 6 teams synchronization will be difficult, very difficult. Synchronization is maintaining simultaneity. You can make a board for more teams, but there yes I agree it’s very ephemeral, you need to question whether the game is worth the candle. And it’s no longer a release plan that is well maintained constantly and therefore always up to date. You can aggregate 5 or 6 release plans maximum for it to remain a living element of decision and monitoring. So no “large projects” with more than 5 or 6 teams? Yes naturally, but you must work on your organizational breakdown: groups of 5 to 6 teams maximum, which themselves aggregate into clusters of 5 or 6 groups maximum, etc. The big boards that aggregate everything are very nice but useless, because not understandable, too dense, not maintainable, etc. The release plan is a monitoring and decision-making tool. That’s what we need.