Last Monday, like every Monday, there’s a dojo at the vaisseau. The vaisseau is the offices at beNext. The dojo is the place where we study. Every Monday we offer the teams on site 1 hour on a topic led by someone who knows about it (the topic, that is). So last Monday it was a dojo on “scaling agile” because we’re often asked (unfortunately) about SAFe. You can imagine that I volunteered.

Note: no participants were mistreated or certified during the dojo.

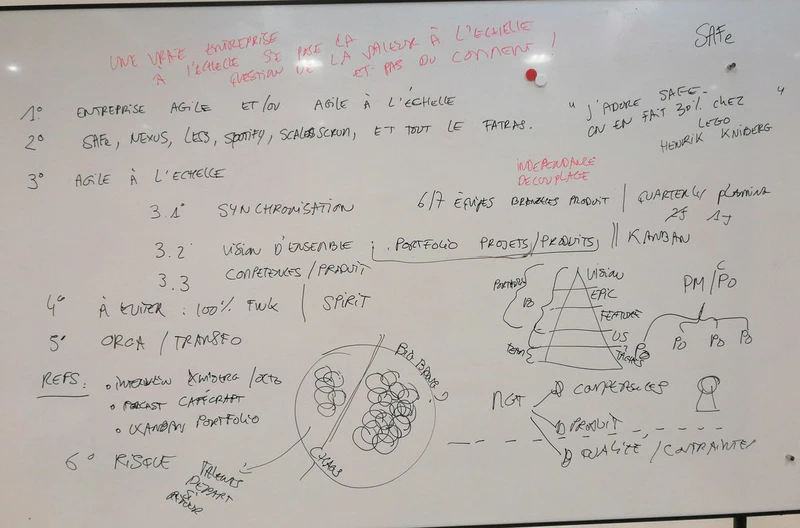

Here’s the content of the dojo that I’m summarizing here, for me, for you and for them: “one hour on scaling agile”.

Agile enterprise and scaling agile

First, it’s important to make the distinction between agile enterprise and scaling agile. The two can overlap, but they’re not the same thing.

- Scaling agile: spreading to the greatest number of teams a way of producing value (potentially only impacts the production apparatus). Intended for large enterprises (large in size).

- Agile enterprise: Operating in all parts of the enterprise in an agile way and with an agile mindset. Intended for any enterprise.

SAFe, Nexus, Less, Spotify, Scrum@scale, and all the clutter

Mid-2000s explosion of Scrum and Agile in people’s minds. Early 2010s until 2015: large enterprises previously haughty, with Scrum appearing only for teams in a fairly unitary way, deign to take a look. But they’re different, they’re big, they’re large, you have to understand when hearing them: “they’ve got it”. They need something at their level. Scaling Agile frameworks (ready-made foundations) are lying in ambush to serve them. Either these frameworks emerged from a company and through feedback and conferences became protected names (Spotify), or they’re downright marketing assemblies made to seduce at any price (SAFe, see the links below).

These approaches are not reproducible as-is and are often alibis for calling yourself agile. You need to look at them with suspicion. Or have fun as Henrik Kniberg said: “I love SAFe, I use 30% of it” (why you should be wary of SAFe and Henrik Kniberg’s presentation at Octo (thanks for the invitation at the time)).

So yes, you’re asked about these frameworks, but it’s a bad starting point. A truly scaled enterprise asks the question of value at scale and not the how (scaling agile podcast at Café Craft).

Scaling agile

How to bring scaling agile back to its essence?

Synchronization

We start with one team then several. We then need to synchronize these teams. Scaling agile is first a question of synchronization. For this, agile has long proposed “quarterly planning” (or other names). During one or two days, every three months (for example), we synchronize the actors of these teams. All actors are present in the same place. Opening for example by the PM (product manager) who oversees their POs (product owners), then each product owner presents their stream (their part of the product, which we hope is dependent), maybe the architecture team, for example, presents the key points for the next three months. And in the afternoon there’s a phase where each team advances on their planning for the next three months (ideally user story mapping format). The day ends with a reconciliation phase of the different plannings, dependencies or not.

From experience, at six or seven teams we saturate the synchronization capacity. But I’ve seen quarterly planning sessions with a limit of 150 people. That’s an intelligent limit. We must therefore think carefully about our organization in departments organized around products with these limits.

As always for an agile iterative approach, we must seek to avoid dependencies as much as possible, to decouple.

On synchronization: Scaling agile: synchronization

The overall vision

Scaling means large size. You need to have a global perspective with adequate levels of aggregation. Scaling agile requires having a good vision of your project/product portfolios. For this, it’s often a Kanban that makes the difference (Portfolio Kanban).

You need a way to see the big picture, synchronicity needs, dependencies, the overall strategy.

We often break down a product into vision, epic (major theme), feature (functionality), user stories, tasks. You can have portfolio kanbans at the level of products or projects, epics or features. The important thing is to perceive the dynamic, the strategy, the macro patterns.

Reorganization of managers and therefore the org chart

An organization that truly tries to become agile must often rethink its structure, its org chart. Very often we end up, and it’s very good, having to distinguish the product manager from the competency manager. For example Gérard - drawing team leader - responsible for Natacha - drawing designer - before the reorganization. He tells her what to do and why and how. After the reorganization he becomes her competency manager: how to grow Natacha’s skill, he supports the how. He now lets Émilie take care of telling her what to do and why. This is not simple for many managers who are used to saying what and how (and who sometimes, often, forget the why).

Questions about organizations and transformations

At what point and at what pace does the organization or scaling agile fully come into play? That is, truly at scale, or when the enterprise truly becomes agile in its entirety? I first thought there needed to be a sort of big bang. Then I changed my mind, I supported a progressive transformation of the entire enterprise, and for the past two years I’ve gone back again, there really needs to be a big bang in my view. Not a big bang for the 8000 people in the organization, but rather a big bang that takes you from 200 to 2000 (2000, 3000 is probably a limit). Generally everything starts with a pilot. But pilots, contrary to their name, are not representative of what’s going to happen. They just give a glimpse. Pilots are done with interested, involved people, in protected environments. And as long as they’re pilots, the organization lets it happen. It’s when you move to the next level, that of the department, real clusters of several teams, that the organization’s resistance truly reveals itself. If it works at this level, say a department, it’s the signal that you can scale.

So why a big bang at this point, that would take you from 200 to 2000, for example? Because there are two types of chaos. The negative chaos that drains your energy. It’s the one where the organization hasn’t chosen. The two approaches coexist: agile and non-agile. It’s a source of pain, misunderstanding, it induces difficulty in reading and understanding. It’s a negative chaos: you’re suffering things, you’re reacting, confronting. Positive chaos is the one just after the switch, just after the big bang signal. It’s chaos, but it’s positive, you know what the target is, and all your efforts are linked to readaptation, to reconstruction. It’s chaos that creates value.

And if you think you can do it without chaos, it’s because you’re not changing anything. Chaos is necessary. You change jobs, you change your life, you change where you live, you change habits, there’s always chaos.

The risk with scaling agile?

The risk is that it starts working up to a certain perimeter, a certain extent. Then for some reason you go backwards. A change in direction, organizational resistance returning to its previous state, etc. In this case you risk losing your talent. People who have tasted autonomy, empowerment, involvement, it’s like having tasted forbidden fruit, it’s difficult to go back. They will be very frustrated. And who will have the easiest time quickly leaving the ship if not your talent?

Link recap

- Henrik Kniberg’s presentation at Octo (thanks for the invitation at the time).

- Scaling agile podcast at Café Craft

- Scaling agile: synchronization

- Why you should be wary of SAFe

- Portfolio Kanban

- User story mapping

- The two types of chaos

- Value Driven Scaling seminar