Here is the continuation of this little story about Scrum, which I remind you is without ambition: a way of telling Scrum, a variation on a theme.

We started the iteration during our previous story (Once Upon a Time Scrum #1). In short we’re in the mud, in the middle of the maul (because it’s really a maul that the Japanese wanted to talk about when observing a rugby match and making a metaphor with their team dynamics, and not a scrum).

During this iteration the product owner validates as we go when it’s done. Done means what? Done is defined by the definition of done (it’s aptly named).

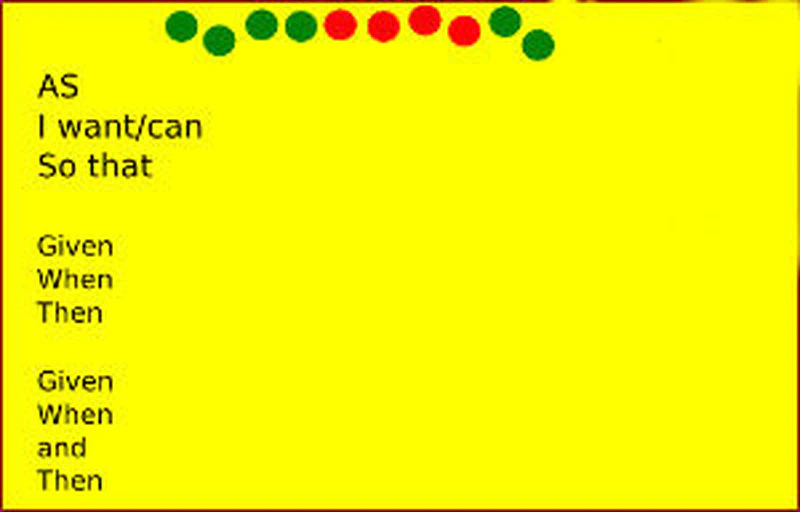

In any case the product owner validates that they got what they asked for, they don’t test if it works, they validate that it’s really what they asked for. Nothing prevents them from doing all the tests they want but the team with its different skills has tested everything before proposing these elements to the product owner. Testing means that everything works as expected, and that it respects the definition of done. Everything’s rolling, it could be put into production in the eyes of the team (it’s not an obligation to put into production, it’s potentially an opportunity). But since it’s the product owner who carries the what and the why and who originates the request it’s they who carry the final validation: yes it’s really what I asked for.

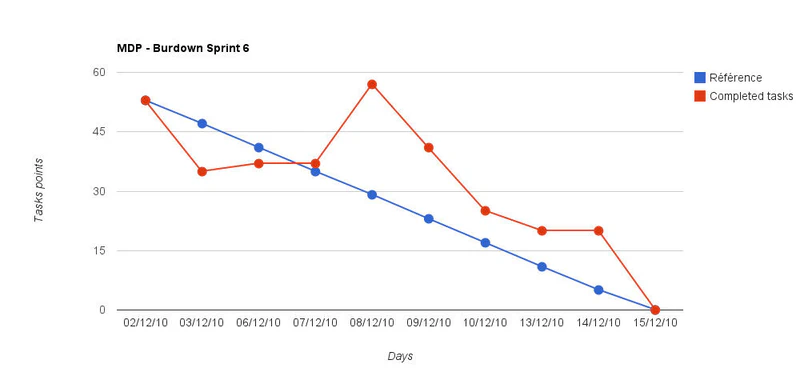

During these working days we’ll realize that we forgot tasks: we’ll add them to the wall of post-its (or remove obsolete ones). The curves (burndown…) will therefore reflect these changes. For burndowns I ask that we break things down into tasks, and ideally these tasks are small. The interest is not really in the estimation, but in the clarification and in the conceptualization of the work to be done. Then with the burndowns we know where on this conceptualized path we are. It is essential to always show the state of things with transparency, without bullshit (in any case, it would show). We won’t incriminate the team: that things change is normal. That there are good or bad surprises is normal, but what we want is to know: to help, to arbitrate.

Moreover for the most stubborn who continue to consolidate the numbers, if you consolidate the tasks of user stories you’ll observe that bizarrely the elements judged most substantial are often those with the fewest tasks because it’s normal we don’t master them well! And conversely the elements judged simplest are those often with the most tasks and that’s also normal because we know how to break them down without worry ! The breakdown into tasks that I recommend aims not to measure but to think through the work to be done.

By the way, no business value on the user stories, it’s untenable. You need to split a user story do you divide your business value by two or not? It’s the kind of questions that mean I’ve never managed to maintain a business value per user story. A real Chinese puzzle, and it’s not really useful. So no business value on the user stories. You can represent the business value at a more macro level: epic, functionalities/feature. The value in the eyes of the product owner, that will be their prioritization.

Every day a point within the team a point takes place (the scrummaster like the product owner don’t need to participate, but the scrummaster as guardian of the method must ensure its smooth running, and even potentially hear the obstacles that hinder the team, in short, it’s paradoxical they’re there without being there). So every day within the team this point takes place: in the same place, at the same time, maximum 15 minutes (standing to remember), to share the state of things between team members. This is the daily standup.

A practice I like is to ask the team for a red or green point representative of their confidence on each element every day. It’s green (we’re confident) or red (we’re not confident). This gives a trend that everyone appreciates. Orange forbidden. Normally nothing red the first day (or else the team didn’t really choose the scope of the iteration…).

After that the team is autonomous and self-organized; moreover I ask not to write names on the tasks. Tasks belong to the team, not to individuals. I don’t want to hear a Laurent (example) tell me “I’m done, but Julien is dead weight and he’s struggling”. First, during the sprint planning it was a team projection, so I don’t understand this distinction between Laurent and Julien, and so they need to figure it out. Second, first the team needs to learn to manage itself so generally I answer: what does Julien think about this when you told him? Don’t worry the team’s self-organization is something that works very very often very well. Like all living systems human beings know very well how to self-organize. Naturally we observe the classic stages of a team when it forms (“forming, storming, norming, performing”, see Tuckman), and it takes 3 (or even 4 iterations) of calibration, but in the great majority of cases it works. Until you decide to change the team, and the calibration must resume. If the problem persists beyond three or four iterations, consult.

This calibration of 3-4 iterations is also very noticeable concerning the relationship and communication between the product owner and the team, concerning the quality of commitments of estimations of projections, etc. And so there too if you change the team, you’ll need to calibrate again for 3-4 iterations for planning (for example).

So generally the product owner spends half the time they grant to the project/product accompanying the team in its realization: they give it feedback, information, validate. And the other half of their time anticipating what’s next: they’ll meet the other product owners, product managers, sponsors, end users, people who influence or who will be influenced by the product/project. With all this information they refine their backlog, their expression of need, change it, redirect it.

Coders code, test, document, discuss, support the product owner for their user stories, dare things outside their usual perimeters. Designers design, code, test, document, discuss, support the product owner for their user stories, etc. Business analysts particularly support the product owner, test, document, discuss, etc. etc. etc. But all that’s the team, they are self-organized. They want to have fun reversing roles, it’s their business, it’s as they want.

If the need requires particular attention: a complicated poorly mastered subject, dependencies with other entities not necessarily very clear, etc. We’ll do refinement meetings, backlog grooming. They allow anticipating troubles, preparing the expression of need so as not to have suffering sprint planning, they allow enriching the product owner’s point.

- Learn more about team formation stages by Tuckman

- Backlog grooming

- A video on a two-week scrum “wall”

- The scrummaster you’ve always dreamed of being, with Jeff Sutherland in the role of CEO.

- Why I like user stories to remain business and not technical, and part 2 of the article.

And the week advances, tasks (on post-its) advance, user stories, functional elements, are validated by the product owner.

Naturally all validation takes place on the integration platform: a clean server, without anomaly (if there’s an anomaly the user story is not validated and returned to the team).

So yes: it’s just impossible to validate a user story with a bug, an anomaly. Either the anomaly is minor, cosmetic, and it’s quick to correct it, so no reason to validate it with this anomaly. Or the anomaly is important and therefore no reason to validate it with this anomaly. Yes agilists are uncompromising on this point (or should be). We don’t want bugs, none. It’s not that we don’t make bugs, we make as many or even more than others (because we like to try), but we don’t accept validating as done something with bugs, we don’t accept releasing something with bugs. It’s not a religion! We’re not the white knights of the bug! It’s quite simply that all these bugs cost more money and more time. We don’t want bugs because we want to save time and money. Everyone has already lived it, observed it, that a bug that’s fixed instantly will cost two minutes, two hours or two days, and that a bug that’s fixed later, will cost double, triple, quintuple… And the 8th bug is it a new bug or is it linked to the 4th? … in short real mud.

Then since we work iteratively impossible to ask the product owner to validate all the first iteration the first time, then the first and second the second time, then the first, the second, the third… it would become crazy.

Also impossible to imagine validating and testing during iteration+1 the result of the iteration, with another team, while starting a new iteration. It doesn’t work, it’s a suicidal flight forward. As soon as we detect an anomaly, and that will be the case without validation or test beforehand, how to handle it? Interrupt the team that started the following iteration? Impossible we systematically trip over ourselves. Only one practice: when it’s done, it’s done, only one rhythm, a clarified reading of the state of things.

It’s therefore also mandatory that what is validated remains in good condition constantly. For this we run regularly (very regularly: several times per day), automated tests at all levels: unit, technical, business, integration, performance, interface, etc. This therefore requires servers (yes Agile costs more in infrastructure, but given the quality and its value optimization its overall cost is better don’t forget, I don’t believe it: I observe it). The real difficulty in automated tests (they’re done by the team naturally!) is first to learn to perform them, to integrate their importance, but especially the adequate data sets, ideally prod-like (otherwise how to really develop?). Data sets that we’ll deploy, modify, delete, re-deploy, constantly… Real reflection must take place on the effort/value ratio, but here’s the direction.

The three episodes of the series and the survival guide:

- Once Upon a Time scrum #1

- Once Upon a Time scrum #2

- Once Upon a Time scrum #3

- Agility Survival Guide (glossary, short descriptions of rituals, bibliography, etc.).

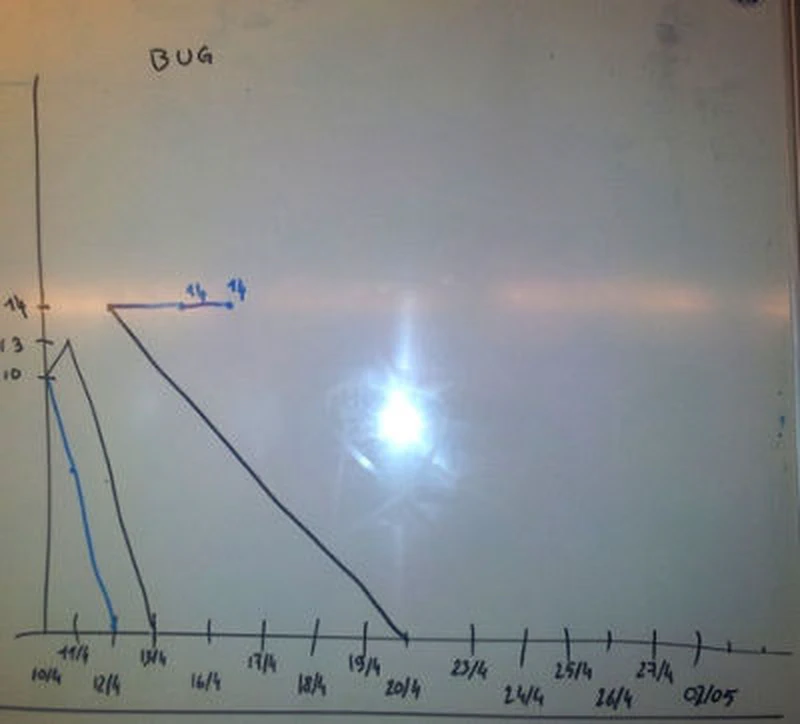

A burndown

At that time (2010), I was still counting points per task (in quarter days: 1=0.25, so normally 4 max, because a task shouldn’t exceed one day, but I easily accepted 8, up to two days). I no longer count points per task, it has no interest, I just count the number of tasks for burndowns, to see if we’re advancing on the planned path, or if we need to act, make a decision, etc. I simply ask that tasks remain small “less than two days”.

Click on the burndown to enlarge. Attention without burnup we could get trapped: let’s say we have ten tasks per user story. They all advance except one per user story. The line would be almost perfect except that at the end we’d have… nothing. But, no value in tasks (which are part of how). Value resides in user stories (that’s why I also like user stories to remain business and not technical, and part 2 of the article). A burnup of user story validation would have shown me that we’re validating nothing as we go.

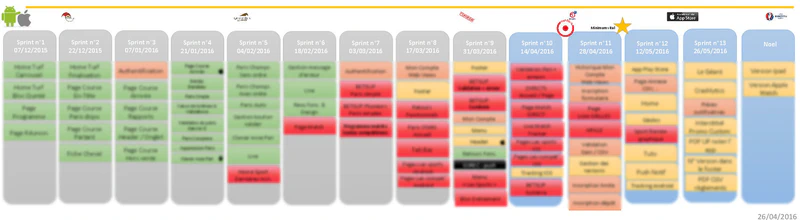

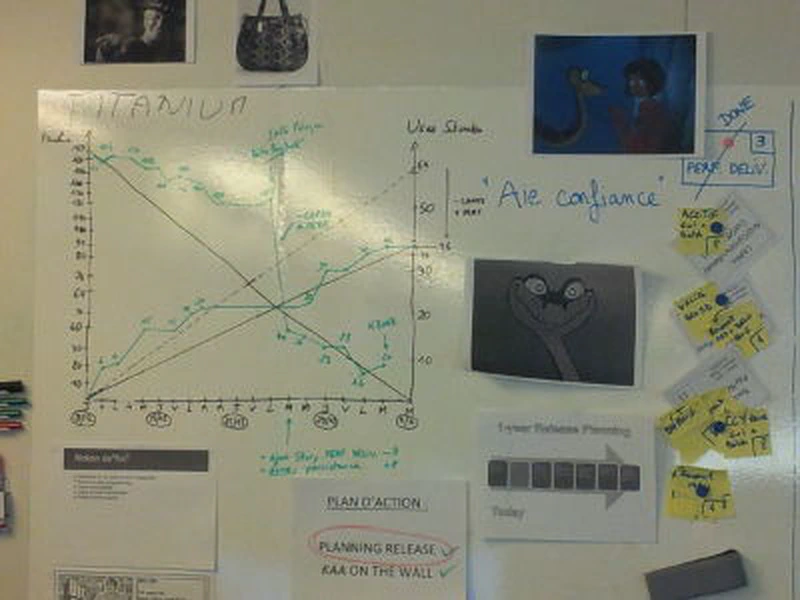

Another release plan

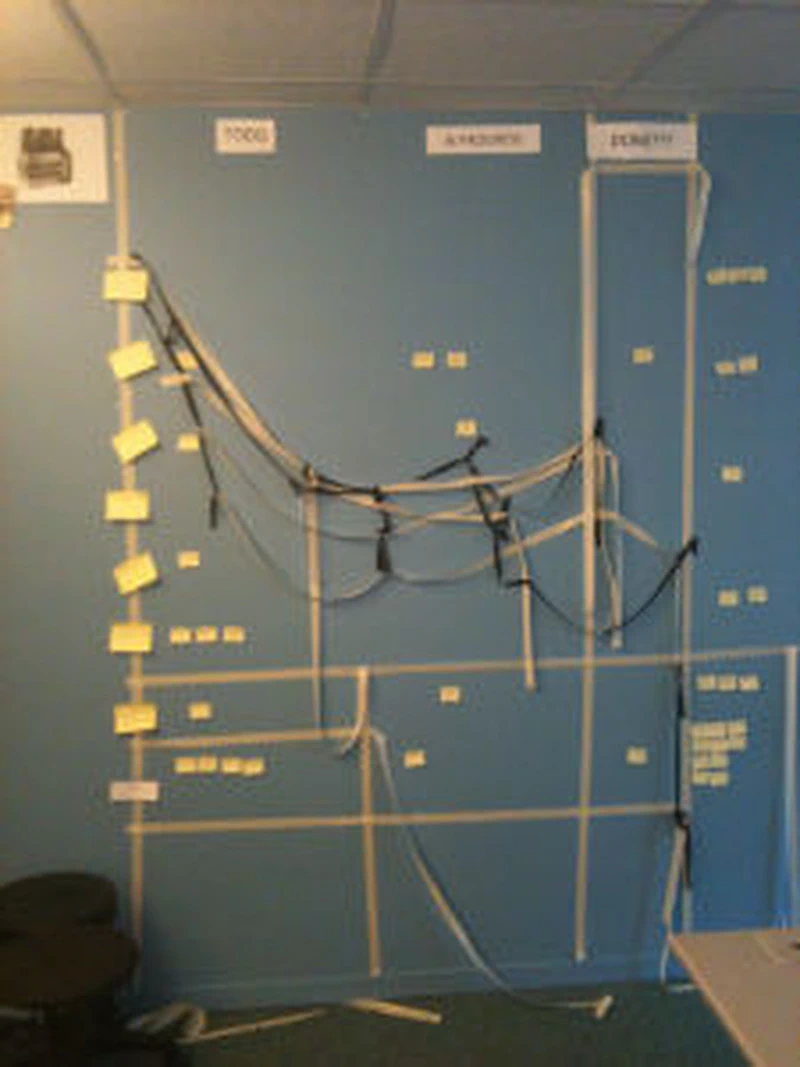

A piece of “information radiator”

That’s what we call the agile “hot” walls: it radiates information. Here we tease the coach by associating them with the snake KA (and we also tell them we’ll turn them into a bag if needed), that was really me. This dates from 2011? We see a release plan, a post-retro action list, a definition of done, a burndown, a burnup? (Click to enlarge)

Visual management: little museum of horrors

Knowing how to be explicit! (that’s irony)

Now THAT is explicit! (that’s also ironic)

Sarcasm (after irony)

- Soft wall, beware of painter’s tape: the first days it doesn’t

- hold, the following ones it tears off the wall. But as I often say

- a failed project/product several thousand euros, a wall to do or redo: two to five thousand euros.

Mushrooms on the wall? Ok to have walls a bit messy: if they’re too clean no one dares touch them and they become fossils, but still a bit of respect, if your walls are sexy they’ll interest people. Try to make beautiful frames.