For a client, recently, I wrote the little story of Scrum. Just a transcription of my speech during my presentations. It’s without ambition, a few pages, and my way of proceeding. To have something more solid, read the book by Claude, who I’m sure will find variations here. Dragos also doesn’t do exactly the same thing. But with these two I agree enough to know that these variations remain details. In any case you can all have your variations on this theme. Let’s say I found it unfortunate to have written this and not publish it… so here are these few small articles without ambition to get started with scrum.

And might as well transform this into a story around Peetic.

- 2012: Episode 1

- 2012: Conversations

- 2014: An article on from idea to release plan

- 2015: A few kibbles

Finally this text will complement the agile survival guide:

- Agile survival guide (glossary, short descriptions of rituals, bibliography, etc.).

My little story of scrum

This April, major projects, we’re starting with Scrum at Peetic. We’ve defined our objectives, they’re simple and clear. We know that a lot of money gravitates around these little creatures (dogs, cats), and we tell ourselves that creating a dating engine for animals could allow us to sell quite a few services and goods around it. The first six months we want 2000 registrations. The following six months 30000€ in sales. Having clear objectives is essential if we want everyone to understand them. These are the objectives with the most value: the most significant. But we need to give relief, six months is already long for us, we’re going to launch into releases, market launches, of three months. Because all our ideas remain hypotheses before really being confronted with reality. “No plan survives the first contact with the enemy” said Von Moltke.

The study phase, preparation, sometimes called sprint zero

As always we want everything, our sponsors want everything, right away. But to succeed with a product and learn quickly, to move from hypotheses to real field learnings, we need to give relief to our achievements. Often we do this during a study phase, or sprint zero.

End of April, we take 5 working days over a period of one month to align, harmonize the points of view and expectations of different actors. Normally the key success criterion is already defined as announced above. This period is the sprint zero or the study phase, or preparation, or the preliminary project, or… 1 calendar month, 5 working days, for 6 months of Scrum, humm, that seems correct.

To harmonize points of view we need representatives from different types of actors, so we find ourselves with coach, product owner, team, designer/UX, business experts, sponsors, users, in short all the people who will be influenced and impacted or who want to influence the project. Of the 5 days to spend we keep everyone the first three. It’s about doing big brainstorming sessions so that everyone brings their vision: technical, business, ergonomics, etc. That everyone brings their constraints and expectations, their ideas, their fears, their knowledge. And especially that everyone hears the other and understands later this or that point of view. Which doesn’t mean that everyone decides everything.

Yes eh, I wanted to say, in Scrum we talk about “dev team” in the scrum team, and many think it’s only about developers in the coder sense, not at all, it’s the team that develops in the broad sense, as much documentation, design, etc, as code.

Learn more about team constitution and co-location:

- A big divergent brainstorming this first day. Let everything be said,

- displayed. The coach will ask during the 2nd day to start

- converging, and ultimately, it’s the product owner or the *product

- manager* (in any case the one who carries the product) in agreement with the

- vision who will prioritize (if needed the coach will use tools so

- that debates don’t become bitter). The important thing is to give relief

- will we do the entire functional scope? maybe. We’ll try to do the best possible with the granted capacity. Thanks to this relief , to this prioritization, we’re going to highlight key paths, key strategic points. All this prioritization, this relief is the responsibility of the product owner, who can naturally listen to each of the actors, but the agile coaches will turn to them to decide. They’re not alone, they can surround themselves well . But we need to choose in the end.

No need to talk about everything the product will imply (that would only be hypotheses, and many would prove false), it’s enough to highlight the key points and then detail them to work during these first three months. Ideally then we’ll go into production to validate our hypotheses: what we develop does indeed increase the registration rate (and sustains these registrations).

Is this not the case? Well we will have only consumed three months to realize that our hypotheses are not good. Phew, instead of realizing it at the end of the program. We’ve succeeded in already having quite a few registrations? Great. We’ve already started to reach a key part of the product’s expectations, and the entire follow-up to the development will be based on fewer hypotheses and more on real knowledge (both technical and user feedback on desires, needs and behaviors).

The following two days are done in a more reduced committee, let’s say the core team: we break down the strategic paths highlighted previously with a field battle plan: we’re going to develop this, then that, etc. We propose a first projection on the upcoming content for the three months but this remains an estimate quite vague (like all these estimates made at the very beginning of an implementation). In any case thanks to our prioritization by value we’ll have the best possible for the allocated time. If we estimate that it’s not enough we’ll see it coming and we’ll make a decision (change the scope? Change the release date?).

- More on estimates: They’re not only linked to complexity.

- More on estimates: The curse of the man day.

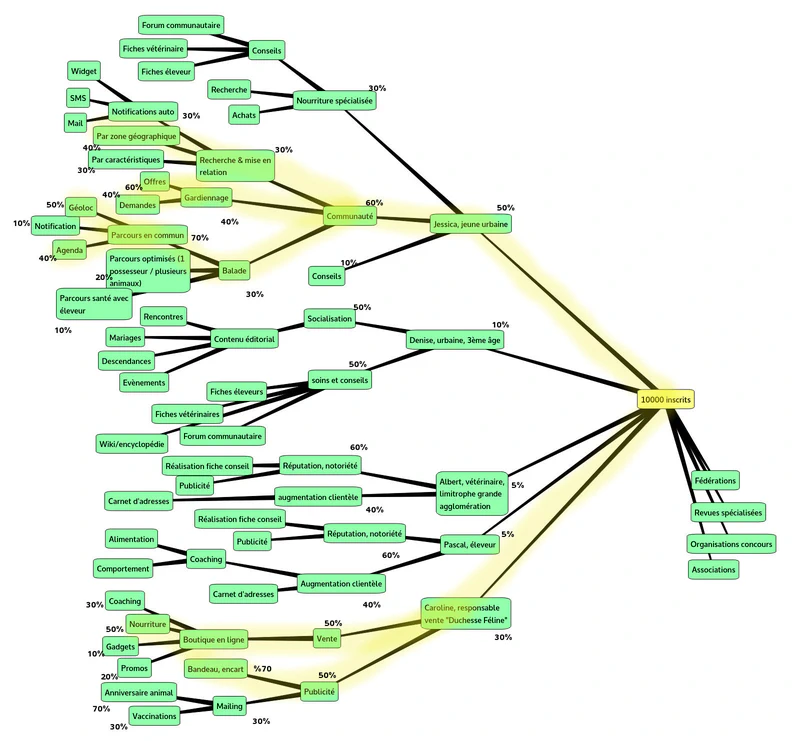

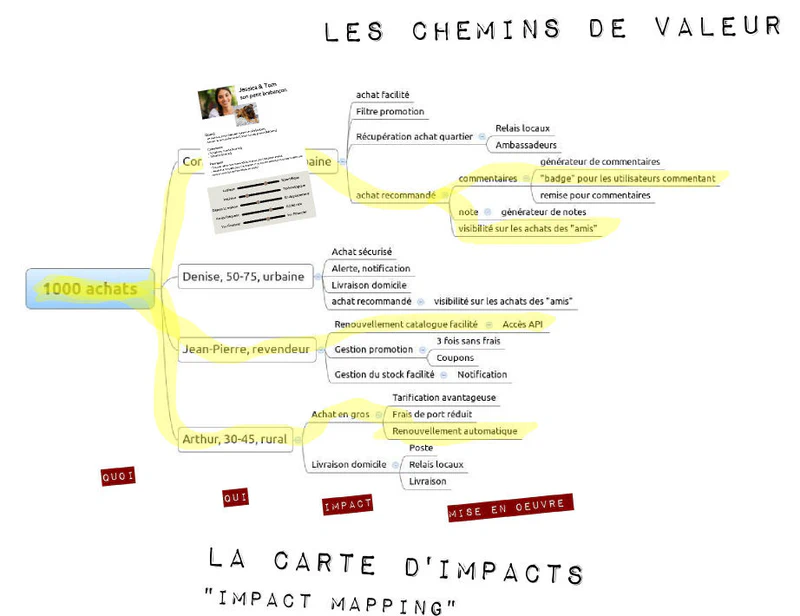

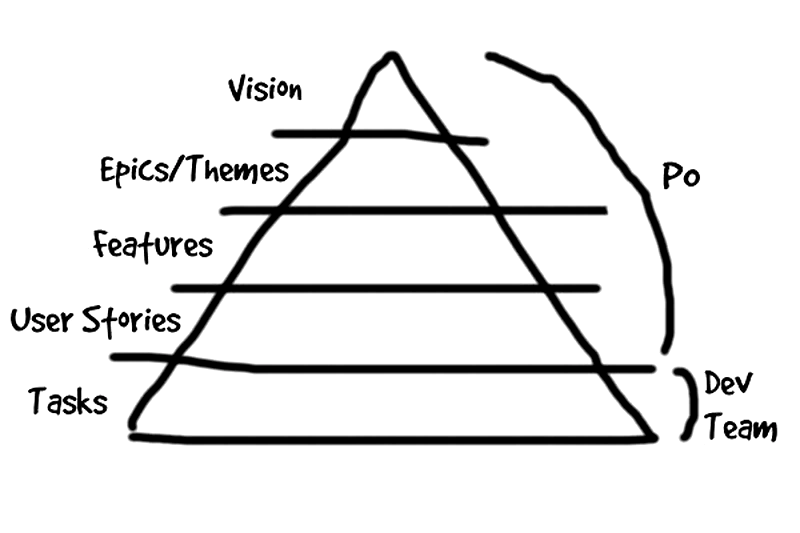

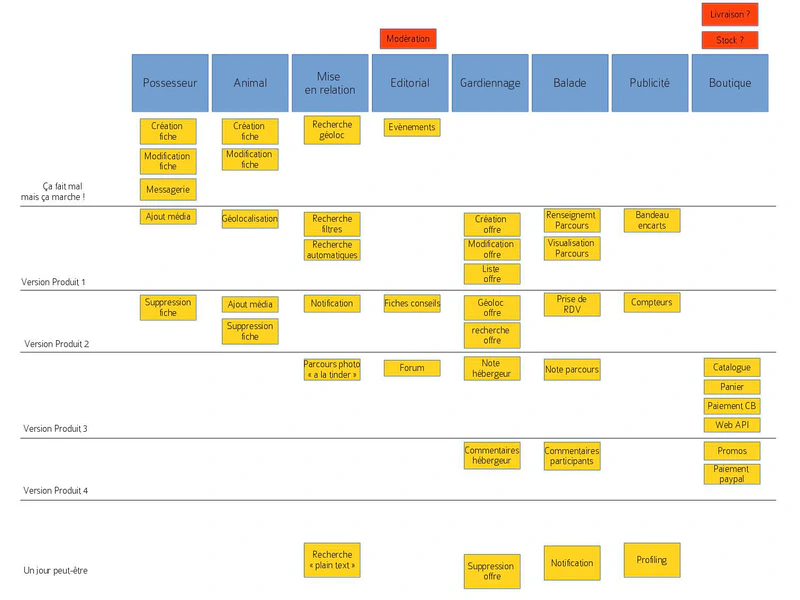

At the end of these five working days we have a) a global framing sheet, with 1 or 2 first key measurable success criteria, b) personas that tell us what the expectations are, what the behaviors are, the characteristics of target profiles, c) an impact mapping that highlights strategic key implementation paths, d) a user story mapping that operationally breaks down (how do we implement?) the strategic paths identified previously. We thought about putting animal owners in touch dating-club style, bam, from our conversations emerged the idea instead of shared pet-sitting, and shared walks. We also specify e) a definition of done that determines our quality criteria: we need to keep it compact so it doesn’t leave anyone’s head. And finally f) A first overall estimate that’s worth what it’s worth like all these first estimates (made by the team), and therefore g) a first release plan: what content should we have and when? Since agile is quite binary in its management of an implementation: it’s either done or it’s not done, it’s finished or it’s not finished (and especially not: “we have 80% of functionality F” which we know doesn’t mean anything), it’s very easy to read the release plans and project ourselves onto sets that make sense on the “business” level. We know the team since they participated in this study phase that we sometimes call by misuse of language: sprint zero. And it’s them who estimate (not the managers, nor only the techies, the team and the heterogeneous profiles that compose it). We’ve also taken care to start specifying the elements at the top of our list of features to develop (what we call our backlog). As always it’s the product owner who decides and arbitrates debates, they can rely on all the skills they want but they carry the what and the why. The team carries the how. The scrummaster and/or the agile coaches facilitate, they are therefore neutral, and take care of the framework to allow everyone to emancipate themselves in it, to take space.

- More on the definition of done: No one is supposed to ignore the definition of done

- More on learning the roles of scrummaster, product owner, and team member.

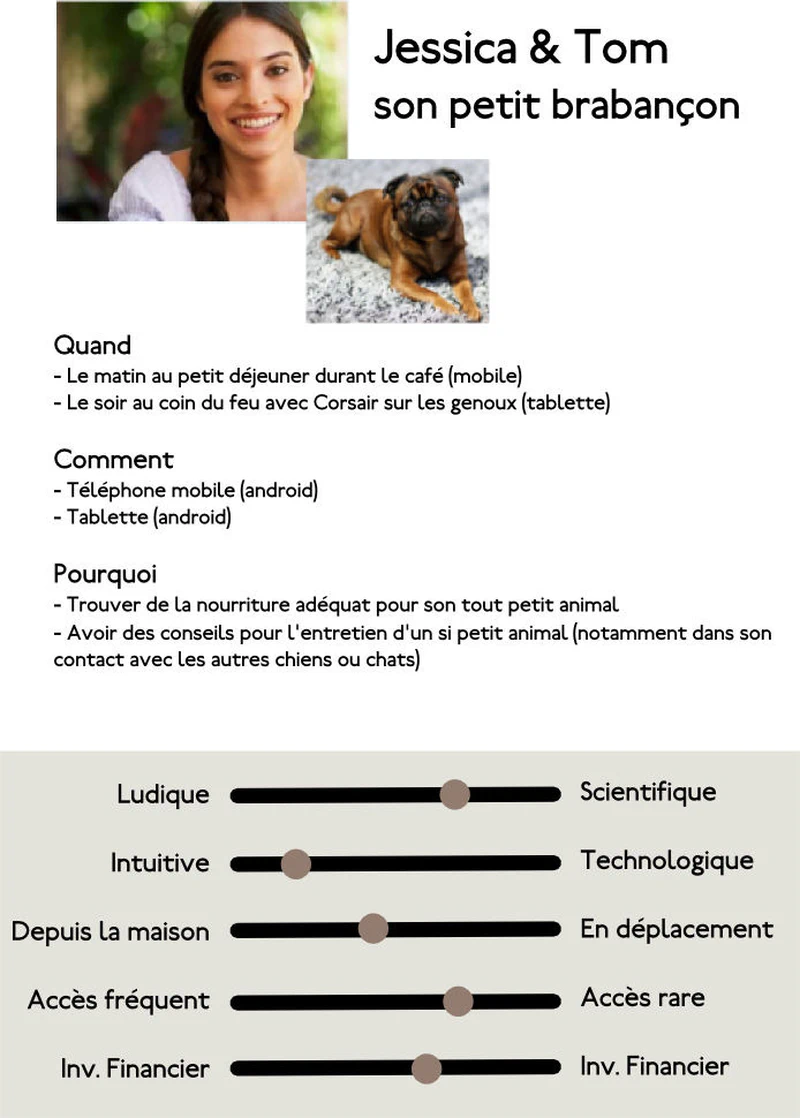

a “persona” (click on it to enlarge)

An impact mapping (click on it to enlarge)

Here’s another impact mapping (click on it to enlarge)

My own pyramid of agile requirement expression

A User Story Mapping

The beginning of iterations

We’re ready, we start the first iteration (of two weeks, they’ll all be two weeks, this regularity is important for our calibrations. Estimation, commitment, and planning: repetition of an observed cadence). A calibration, an adjustment, takes three to four iterations (whatever the duration of the estimate… it’s living a cycle that’s important), so the shorter the iterations the better. We calibrate faster, we learn faster.

Monday morning is dedicated to the sprint planning. The Scrummaster made sure that invitations were sent, that the room is reserved, that everyone is aware of the meeting content, and that the necessary equipment is there (post-its, paper, projector, etc). We’re going to have a conversation about the backlog features. One by one: in the order of the backlog, that of value for the product owner. Until time runs out, or almost. The objective is to detail the expectations well, to raise unknowns, misunderstandings. We use conversations around estimation to make them obvious, to clarify everyone’s points of view. The PO doesn’t estimate. Neither does the scrummaster who is neutral (they do nothing to have the power to free the team’s productivity). The debates are fascinating for everyone. The business, the PO (product owner), discovers that the techies aren’t trying to screw them, and understands why sometimes something simple ultimately isn’t, and why sometimes something complicated proves simple sometimes. The techies understand that the business, the product owner, doesn’t have mental health problems and doesn’t change their mind to annoy them, but for good reasons. Fifteen minutes before the end of the meeting the scrummaster alerts everyone: we’re going to have to project ourselves on what’s achievable in the coming two weeks. The product owner chooses the order of user stories, features, the team announces how far they think they can go. What they think they can finish. Because agilists are maniacs: either it’s finished, or it’s not (as much as they’re perceived as cowboy hippies, they’re binary on this finished/not finished point). Naturally finishing means respecting the definition of done (quality, technical aspects, etc), and the business functional aspects on which the conversation with the product owner just took place and whose final arbitration remains with the PO. So this is the moment when we ask the team: how far do you think you’ll go? Let’s say the team tells us the first 5. That’s the sprint backlog, the imagined scope of the iteration.

An important rule: we want to avoid tunnel effects. Thus we don’t want user stories that could finish in the allocated time, the two weeks, and we want at least three. This induces a rule: can only be taken in the iteration user stories whose effort is less than a third of the iteration duration. During sprint 0 the first estimate will have allowed alerting the PO to important user stories whose estimate widely exceeds this maximum effort (I’ll talk about estimates another day). For the PO this is an important message: they must break down the user stories into several smaller user stories (and believe me they don’t like that) if they want the scrummaster to authorize the team to be able to implement them.

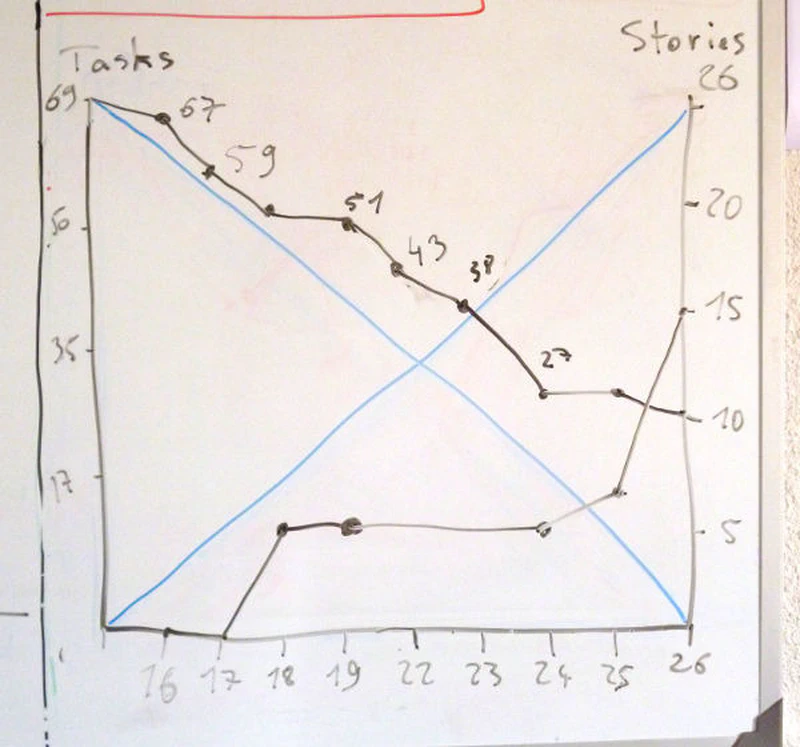

There we have the iteration content: the first five user stories of the backlog. They leave the backlog (which belongs to the PO) to fall into the team’s hands. The team spends the afternoon (two new hours) breaking down into tasks the user stories: what will be the necessary tasks to achieve these user stories according to the expectations of the definition of done and the business expectations discussed previously with the product owner: code, documentation, tests, design, datasets, etc etc etc. As much as the PO doesn’t like breaking down their features (they naturally want everything! but we’ll have everything we want to break down to progress serenely, feel our progress, better address questions, have feedback, etc.), the team doesn’t like breaking down into tasks either! Thinking before doing is a habit to develop because this breakdown is design, design ultimately. And it will allow us to know where we are (“remaining to do”) during the two weeks through burndown (of tasks) and burnup (of stories)

There we go, the iteration begins. What will happen during these remaining 9 days? Team members will try to produce, implement what will have been defined during the sprint planning. Every day they’ll show the progress of their work with a visual wall of post-its. This wall serves to synchronize them with each other and to communicate to the outside world. They’ll also follow their work by creating a burndown: a descending curve of remaining work to do (for the burndown I count tasks and I decrement when they arrive at “done”). And a burnup, an ascending curve, of validations made by the Product Owner. Because indeed we hope, we wish, that the product owner validates the user stories, the elements defined during sprint planning, as we go, to limit risks and pressure. By validating as we go no surprises, no pressure. We regularly get feedback, and we regularly raise hypotheses. Quality comes from regularity.

Supplements here or elsewhere:

- A typical morning of a scrummaster, by Claude

- A revealing afternoon of a scrummaster, by Claude

- The day I discovered I was a bad scrummaster, shameless lie by Géraldine.

- From scrummaster to agile coach, a classic journey

- Understanding MVP by Frank who translated a text by Henrik Kniberg

- Introduction to product owner strategy, still relevant with Alexis, from Praxeo, my Jerry Garcia period.

- The sequel with The product owner strikes back,

- And the last part on product owner strategies (still in my Jerry Garcia period)

- You can always take a look at the Scrumshot (it’s svg)

- Learn more about cowboy hippies

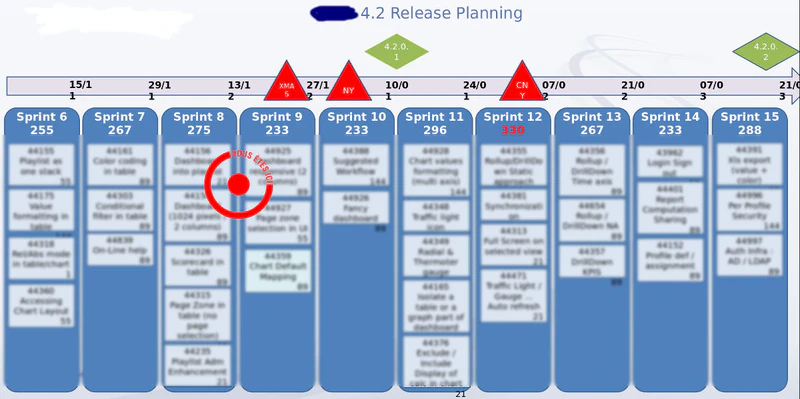

Here’s a release plan (click on it to enlarge)

A scrum wall

A burndown and a burnup

The three episodes of the series and the survival guide:

- Once upon a time scrum #1

- Once upon a time scrum #2

- Once upon a time scrum #3

- Agile survival guide (glossary, short descriptions of rituals, bibliography, etc.).