All agile emergence plays on a paradox that is always difficult to master. On one side, there’s the need to fuel the emergence of a contextual response, and on the other, to learn through respectful practice. Unfortunately, very often under the guise of adapting to context, we are disrespectful of the practice, and quite often this adaptation to context hides the resurgence of our habits rather than real change, rather than genuine adaptation.

Emergent complex system

People and companies are right: each Agile will have its own personality, its own definition, depending on when and where it is implemented. This is the very idea of agility - this adaptation to context that tends toward the most adequate response, the one carrying the most value for the minimum effort (something very natural, this minimum effort; quite often in nature, elements are lazy, many forms are born from an economy of energy). This observation seems simple, but it is not. This adaptation to context also implies that when the context changes, the adaptation changes too. And believe me, the context changes constantly. But let’s come back to agile transformation: we cannot deny that each transformation, each context, has an adequate (agile) response. And we also cannot refute an observation that all change agents make: you don’t take people or a company where they don’t want to go. We don’t want to, and it’s not possible.

So, like any emergent complex system, it is by definition emergent, and therefore adapted.

Learning

Recurring problem: this adaptation should come from learning, this adaptation should challenge certain practices of a doctrine, a reference; unfortunately, very often we don’t take the time to learn, we short-circuit immediately. Very often people and companies decide they already know the necessary adaptations, and this is often a mistake. Old habits die hard - it’s often muscle memory speaking. Especially since Agile is a real leap into another paradigm, it’s difficult to project yourself without experiencing it first.

This emergence often needs to feed on orthodox learning.

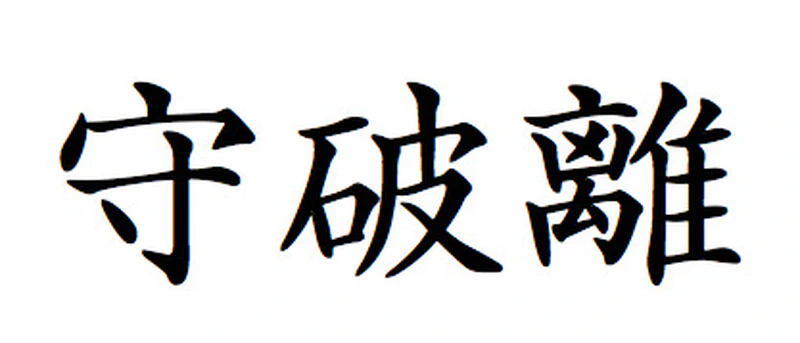

Hence the regular mention in the agile movement of the Shu-Ha-Ri ideogram. This imagery comes from martial arts.

SHU

Do what your mentor asks you to do without flinching. Apply the rule, practice, and practice again.

HA

By doing, you’ve truly understood how it worked and now you can make contextual adaptations.

RI

You’ve integrated the teaching, you do it intuitively (breaking the rule or not).

So on one side we cannot deny the emergence of a contextual response, on the other the need to respond initially in a very orthodox way, or rather to base this adaptation on real knowledge of the new paradigm. This learning of orthodoxy (of the new paradigm) is far too often ignored. Either because we don’t understand its importance, or because it’s impossible to implement (for good reasons).

We must understand its importance; I can’t provide other answers on this point. Without a reference you’re moving forward with your eyes closed, and with a paradigm shift this is not just a figure of speech. Concerning implementation difficulties, it’s often the use of “demonstrators” (one or more teams given the means for orthodoxy and learning). We need to know how to suspend our beliefs to let the right answers emerge, without believing too quickly that we’ve spotted them.

The intention behind the agile transformation is therefore naturally key. It’s the intention that grants the means.

Changing

The last blocking point (after raising awareness of the importance of learning orthodoxy, and the ability to give ourselves the means, to suspend our beliefs) is the ability to go backward. This last point is very foreign to our societal habits: when a law is passed, we’re not used to hearing “actually it’s not working well, let’s go back.” That’s a real shame. Yet to facilitate change management, the ability to truly try, to truly suspend our beliefs, it’s important to be protected (by demonstrators as mentioned above, or using a technology like open agile adoption, etc.) and therefore to be able to go backward. Without protection we’ll protect ourselves by resisting change. We must be able to take one step back to quickly take two steps forward. Here again, the intention behind the agile transformation is key; if it’s valid, it will know how to give itself the means for these backward steps.

Our paradoxes

- Emergence relies on orthodox learning (and not on our habits or our desires).

- Adapting to a context that doesn’t wait to evolve (so we adapt constantly).

- Moving forward in a direction while suspending our beliefs (trying, daring).

- Knowing how to change means allowing ourselves to go backward (one step back can lead to two steps forward).

In fact, because of its acuity on all these points, Agile has also become an all-terrain change management technology.

By recently deciding to change organization and adventure, officially leaving the company I had founded with Gilles and Christophe to join David at beNext – believe me – I’m practicing change. It’s salutary for someone like me; I feel all the sentiments I mention above. I draw an essential lesson from it: change is first and foremost a fantastic learning accelerator. (Official start October 1st).

I think this article should be read alongside the following: