During this TGV journey on Sunday, January 18th in the year of grace 2015, I took the time to annotate my bibliography for the consolidation of work for a client. I took advantage of this effort to append it to my survival guide following training. And as a result I also added the starting point of what I hope will be a new mini-book on my reflections (a sequel to the agile horde). This starting point consists of three tables: modernity, agility, engagement. For those who follow me, and I thank them warmly, this is not necessarily very new, for others who might be interested in it, and I thank them too, this is a good synthesis of my current reflections on our environment.

I really hope to finish before spring these “living organizations”, this sequel to the agile horde, but for now I’ve lacked time, as well as the cannibalistic aspect of my reflections: I think I’ve settled on these, but new ideas emerge and nibble away at the previous ones. And above all I’m seeking a coherence that may be vain.

Three Tables

I would like to describe three tables for you, three starting points describing the world in which I evolve.

The first table deals with the two methodological and organizational approaches that have shaped recent centuries: that of Ford and that of Toyota. The goal of this first table is above all to highlight that each era has its own response, and that no response is the right one isolated from its context.

The second table deals with agility, this term that is becoming overused, but which still represents a great deal to me. Agility which in itself is the culmination and synthesis of our understanding of our new complex world.

The third and final table deals with people’s engagement, a key point that synthesizes the first two tables.

Modernity

Looking at the last century and concerning the organization of our companies, one could distinguish two fairly different modes of thought. For each era (early 20th century, late 20th century) adequate responses, but very different because they didn’t respond to the same issues, were proposed. These different responses are quite well highlighted by the comparison of Fordism and Toyotism.

At the beginning of the 20th century, when John Ford announces “people can choose any color for the Ford T, as long as it’s black,” he is right, no one is yet thinking of all the progress and variations that will follow. Ford is revolutionizing our habits with the car which from this moment becomes man’s best friend. But at this time no one questions the color or shape of their car, the question is whether to have one or not, quite simply. Other traits characterize this era and this way of approaching work: the workforce is very cheap, in surplus, untrained, Ford will therefore base his strength on quantity and not quality; it’s the hour of glory for Taylorism. This Taylorism is very well justified given the context that sees it born.

At Ford we also observe that the last step before the release of the famous Ford T is quality assurance, testing, acceptance in a sense. And we sort: this car leaves, this one doesn’t. Nothing very shocking for the era, raw materials are not lacking.

When a car leaves, it comes with a guide concerning the 150 most probable or frequent anomalies. There too, nothing shocking, at the beginning of this century one need only dive into this manual, arm oneself with a good hammer, and the job is done. Car repair is not a Chinese puzzle, and remains accessible to ordinary mortals. It is therefore preferable for Ford and the consumer to leave these anomalies to its customers, the cost is better for everyone.

Forty, fifty years later, at Toyota things have changed a lot. It’s a country destroyed by war that one discovers. Raw materials have become a critical element. One cannot waste or stock excessively. Machine tools are also a rare commodity, they will need to be exploited to the maximum of their possibilities. In a certain sense, just like the men, who, at the government’s request to restore the country, are hired for life by Toyota. Technology has also changed, and it continues to change. A hammer is no longer enough to repair your car. Finally, public expectations are no longer the same. The Japanese firm is therefore at the antipodes of Ford’s situation. Different era, different customs.

Toyota’s response is also revolutionary: to get the best from its employees, who will accompany them all their lives, the firm understands that the best way is to respect them and empower them to the maximum. It is moreover by empowering them that it gets the best out of its machine tools. The man in the field demonstrating an undeniable capacity to adapt these machines and to have ideas to exploit them optimally. Reflection for continuous improvement becomes a common practice among them. This practice is not limited internally, suppliers are encouraged to find ways to improve their products or their production capacities: they will only pass on this improvement two years after it happens.

To address the stock problem, Toyota discovers that the best cost comes from two things: a) intrinsic quality: as soon as an anomaly is detected the chain is stopped, the impact and correction of this anomaly will be minimal, and the affected stock minimal; b) a just-in-time management regulated by active participation from employees, it’s they who pull the flow (they fetch and trigger their actions which thus adapt perfectly to their rhythms and their competence, hence also strong empowerment), and it’s not a pushed flow (there employees undergo the rhythm).

These are not ideological responses in correlation with each era. We’re talking about industry, companies, whose reason for being is to generate profits. These were the best responses in terms of business performance.

Today many of our companies still evolve under the model of Fordism, but it is indeed, even if it too is gradually becoming obsolete, Toyota’s model that should inspire us: intrinsic quality (not because it looks good, but because it costs less and generates more revenue), empowerment (not because it looks good, but because it generates more value, more revenue).

I deliberately insist on the purely economic aspect. It’s not necessarily my cup of tea, but I myself evolve in a competitive environment and I know that this is the nerve of war for the companies that call on me. The good news is that to make your business succeed today you must engage and empower people as Toyota was able to do.

Agility

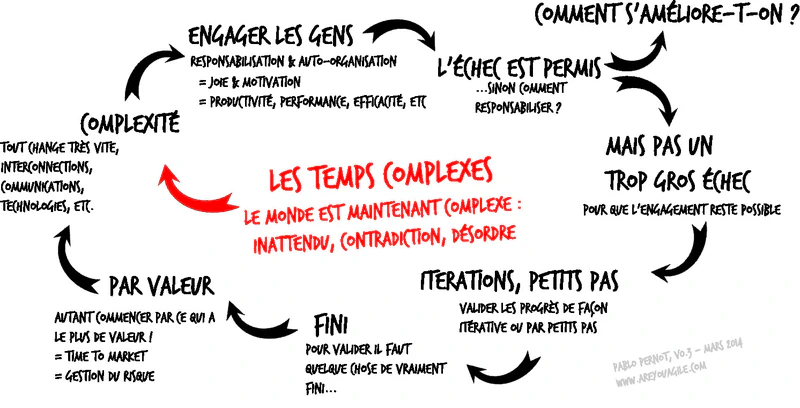

This response to modern times from Toyota is what is called " Lean." The heir of “Lean” is the “Agile” movement: the intensification of communication, the renewal of competition, markets and technologies have made us tip into complex times. To understand Agile in relation to Lean today, one must remember adaptation and not industrial standardization.

We have entered complex times: everything goes very fast, too fast, everything is intertwined, everything changes, all the time, etc. The best way to respond to this complexity is to empower, to engage people. Like a general who can no longer direct everything as 200 years ago, and who must rely on the self-organization of his troops, they remain faithful to his strategy, to his vision, but implement their tactics.

This empowerment (and thus the liberation of this capacity for performance) is only real if we allow the right to error, otherwise it’s just a pretense and the expected effects are not forthcoming.

But empowerment is also possible if it doesn’t put the organization in danger (or the project, etc.), otherwise who would dare anything?

It is therefore necessary to support empowerment, but only if error is possible, but it must not be “fatal.” For this we must move forward in small steps, iteratively. And judge step by step our progress. A small fever, that heals, a big one, that kills!

But to truly judge, you need finished things. No matter the iterative approach if things are not finished (it’s then incremental…). Question yourself very deeply about this notion of finished (the best is to put on the market! think about the minimum viable product). We will have real feedback, real answers, only with finished things.

If you succeed in delivering finished things, step by step, while expanding, then you might as well prioritize by value. Because a) you never have time to do everything, so you might as well do only things of value, b) this allows you to give yourself the greatest guarantees and the greatest lessons, and finally c) to have a significant “time to market” (that is being able to put on the market very reactively).

This “Time to Market” is very useful in these times of great complexity, because everything changes so quickly.

Naturally this cycle is only learning (it’s necessary in this ambient complexity) if we constantly question ourselves about how to improve. There in a few words is what carries in my eyes the notion of agile today, an adapted response to complex times: empowerment, feedback, learning, time to market. The complexity requires emergence (feedback, learning and thus time to market), which requires interaction (empowerment, continuous improvement, collective intelligence).

Engagement

Toyota, Lean, then Agile: we constantly evoke empowerment and engagement. But it’s vain to say “be motivated!”, we know the absurdity of such an approach.

Recent Gallup studies indicate that only 13% of employees worldwide do not feel involved, or don’t want to be. This opens the debate on the performance of our organizations.

In the Mythical Man Month the author (Fred Brooks) expresses the idea that a person (in his case, a software developer) has a productivity ratio of one to ten depending on context. Their capacity would thus fluctuate from one to ten depending on context. My observations -on myself and others- tend to confirm this information. And I think that the large part of this gap comes from the person’s involvement. Observe yourself performing a task on which you don’t feel involved, and one on which you feel involved, that you have taken ownership of.

One cannot decree motivation, nor involvement, nor ownership. So let’s observe the areas where they are flourishing, one of these is well known and has given rise to studies on this involvement: video games, and rather video game players.

We observe that involvement in a video game is often much greater than that in business life. All these players of online games who pay to fail, start again, learn, redo, provide quality documentation, couldn’t we have the same engagement in business? The video game industry is flourishing, understand that it involves enormous sums of money. Before therefore for ourselves drawing lessons from it for the organization, it questioned itself, because its success is linked to the involvement it will generate. The observations that resulted from this research are a goldmine for us.

But as I evoke this subject, I receive my eldest son Mathieu’s school report. Mathieu has good school results, but the report indicates that if Mathieu were involved he would have very good school results. I look for Mathieu:

- Mathieu? Mathieu?

- (from the other room) Yes dad?

- Can you come so we can talk about your school report.

- Wait, I can’t right now, I’m building the fourth tower of my castle 4 and it doesn’t have exactly the same decorations as the others nor the same iron construction, I can’t leave it like this.

- Yes, that’s exactly what I want to talk to you about…

In other words, Mathieu is very involved in his game, and his results are very good. What is the school missing to obtain this same engagement? What is the business missing to have this same type of involvement? This is the synthesis work performed by Dan Mezick.

One last detour through my eldest son’s school. Parent/teacher meeting, I’m face to face with the main teacher, she complains about the general quality of the class, its lack of seriousness and the level of its work. Then we move on to the recent educational outing to archaeological excavations (several days on site). She delights in the success of this event, and in the minutes that follow tells me that the class provided excellent work and a dossier. Surprised, I therefore question her about the gap between the daily work and this work. She remains silent for several seconds as if a trap had closed on her then slides to me, a bit unsettled: but we can’t do new interesting things like that all the time. I remained silent thinking that it was indeed the education and life of our children we were talking about then.

Let’s also make an obvious connection with our companies: if you do things that interest the people with whom you work, if you succeed in involving them, what results will be nothing comparable.

So what do these studies on involvement in video games teach us? Simple, obvious things, but too often forgotten, or neglected. For a game (or a company) to generate engagement it must offer:

- A clear objective: do we have clear objectives in our organizations?

- Clear rules: do we have clear rules in our organizations? A well-defined framework?

- Feedback: do we regularly have feedback? Do we know where we are? What is the result of our latest actions?

- The game is an invitation, no one is obliged to play: does this notion of invitation exist in our organizations?

By offering this framework, the game (or the organization) will generate several feelings that are the basis of this involvement and this fulfillment.

- A sense of control, in the sense of mastery, I can act and I know how to act.

- A sense of progress, I’m moving forward and I observe that I’m moving forward.

- A sense of belonging to a community.

- The feeling of working for something beyond me, something greater than oneself, one projects oneself into an achievement that surpasses us.

These are simple points, but crucial to involvement.