Chapter 1: Agile World, Complex World

“No plan survives first contact with the enemy” – Von Moltke

The present text aims to represent my reflections on dynamics within our organizations, particularly around my activity of organizational coaching support. I work with organizations. I aspire to support them, see them grow, adapt, evolve. Like a living organism, they adapt or die. After a century of industrialization, our ideas about organizations are distorted. The model of our parents’ and grandparents’ companies is in poor shape. And good riddance. Because the world has evolved. Naturally or forced by the assaults of our way of life. Other horizons call for other responses, other ways of doing things. I work as a mentor1 or coach of a movement called Agile. The organization is also currently the strongest social link. That’s where I spend the largest part of my time. That’s where I make the majority of my encounters. That’s where the majority of my social interactions take place. Socialization is one of the defining traits of our species. Let’s be attentive to how we treat it.

Today we must meet three challenges:

- That of the complexity of the recent world.

- Its frugality, the preservation of our resources for our survival.

- And the immateriality provided by technological advances, value is in information, in knowledge that flows through all networks. I propose to go in search of the responses we could bring to these three challenges: complexity, frugality, immateriality. At least those, modest ones, that emerge from my daily activity.

Complexity

Companies, managers think they need time and money, more time, more money.

They are mistaken. In the complex world, changing, fluctuating in which we live, it’s neither having more time nor more money that makes the difference. What makes the difference for companies, for managers, is an ability to engage the people with whom they work, because the gap between the impact produced by an unengaged person or by an engaged person is immense. What makes the difference is maximizing the value of what we produce while, ideally, minimizing the efforts to produce it.

Forget time and money. Focus on engagement, empowerment, involvement of the people you work with, and ensure very regularly that you produce the right things. The current enthusiasm for the term Agile is nothing other than the translation of that.

Agile is ultimately the marketing term for complex. Saying you want to be Agile is first acknowledging that the world is complex. Complex comes from “intertwined”. Needs evolve, technologies evolve, communication is global, instantaneous. It’s now impossible to deny that things, projects, products will live partly unpredictably, that the unexpected will be there, impossible to have certainties in this complex world. Being agile means knowing how to evolve in this complex world. And, you’ll agree, Agile is an easier term to grasp than “complex”. I doubt you hired a “complex coach” or launched a “complex transformation”.

So being agile means knowing how to evolve, being high-performing (another magic word) in this complex world. How is this implemented? The first thing for managers is to learn to let people take responsibility, be autonomous. When a person is empowered, is autonomous, they become much more easily engaged. And engagement considerably multiplies the impact of these people. You know very well yourself that when you undergo things without being able to control them, without wanting to, without having a say, your performance is, how shall I say, very mediocre. At least that’s how it is for me. And if on the contrary you’re engaged by being empowered, having decision-making power, autonomy, you become much more involved, much more high-performing.

Remember those battlefield stories where generals camped from the top of their hills dictating to each of their soldiers or squads the movements and actions they had to perform. It’s hard to imagine such a setup today, in modern warfare. If a troop or commando doesn’t have autonomy, it will be far too slow, far too inefficient, far too vulnerable. Empowering it, giving it autonomy, makes it much more effective, but it’s not letting it free to do what it wants. This imaginary troop has a clear objective, it must destroy a certain bridge, it has clear rules to respect: it can’t go to a certain place because enemy forces are present, it mustn’t destroy another structure, etc. It’s no longer the gesture you dictate to your teams, it’s the framework: the objective and the rules you clarify. It’s up to this team, these people, to take this space, that’s what makes all the difference in terms of impact of performance or innovation compared to following a step-by-step, fossilizing process.

Being agile, evolving in this complex world, is thus first empowering, giving autonomy, giving decision-making power on a whole set of subjects. Modern management is thus first a letting-go, a laissez-faire, and a clarification of the framework and rules. But people will only be autonomous, responsible, if they have the right to be wrong. Otherwise your so-called empowerment is a lie. It’s only if you have the right to be wrong that you can serenely make the decision you think is best all the time. If you don’t have the right to be wrong, your decision is clouded by other considerations, you no longer choose the best. Here again a fundamental difference is made. For this authorization to be wrong to be easy to give, we’ll try to work on small pieces. If we’re wrong about a small piece, it’s not serious, if we’re wrong about a big piece it’s more troublesome, implicitly if you work on big pieces you forbid yourself to be wrong. Small iterations, few things at a time, there are several strategies, but we work on small things to have the implicit authorization to be wrong, we don’t have the trouble of protecting ourselves.

Being agile, evolving in this complex world, is thus empowering, making autonomous, to transform the impact people can have by taking this space. Authorizing people also means authorizing them to be wrong. This implies a large share of continuous improvement the goal not being to be wrong. To easily authorize people to be wrong, so the prohibition isn’t implicit, we work by iteration, or on few things at a time.

Here there’s another important parameter that people don’t necessarily grasp. To have a true look, true learning, true observation on what we’ve produced. To ensure we’re not wrong and thus say it works, or it doesn’t work. To have this look, this feedback one would say in English, and for it to be real, we must observe finished things, things that make sense by themselves, small pieces (we said we worked on small things to authorize error) autonomous that make sense. For example, don’t tell me you’ve prepared your entire data model for future financial reports. When adding business objects, the user interface, ergonomic aspects, things will change. We believe we have something finished, but it’s an illusion. We perpetuate the risk of being wrong. It’s not good for anyone. Something finished would have been one of the reports or even more simply a figure from one of the reports, etc., but that would have implemented a piece of interface, a piece of algorithm, business object, a piece of data storage, thus a vertical approach. And especially this small autonomous piece making sense produces value by itself. It already brings something useful by itself.

Being agile, evolving in this complex world, is thus empowering, autonomizing, to transform the impact people can have by taking this space. Authorizing people also means authorizing them to be wrong. This implies a large share of continuous improvement the goal not being to be wrong. To easily authorize people to be wrong, so the prohibition isn’t implicit, we work by iteration, or on few things at a time. To be sure we’re not wrong we cast a look, feedback on the things produced, and to be able to really judge them, these produced things are small autonomous pieces making sense.

For management the change in posture is letting-go, laissez-faire. For business people, product people, it’s this ability not to arrive with a globalizing solution, but know how to cut into small autonomous pieces that make sense, carrying value, and that will gradually fill out.

It’s to know how to produce these small autonomous pieces making sense and carrying value that all these organizations recompose into multidisciplinary teams: to have this autonomy, this ability to deliver very vertically. Among other reasons.

To this reflection on being agile, on the complex world surrounding us, we must add a parameter: we don’t have time to do everything we’d like to do, we very very rarely have the capacity. Being agile, evolving in a complex world, is thus also an ability to prioritize by value (learning value, concrete value, etc.). Thus we arrive at the promise of being agile: If I’m capable of empowering and autonomizing I multiply the impact and performance of people, and if I know how to deliver small autonomous pieces making sense, bringing value, and prioritized by it, I know how to read, listen, learn, bounce back on my market. I save by failing fast. I reap benefits more quickly by not waiting to deliver sets of things that are too large.

To evolve in this complex world, to be agile do what you want as long as you empower, you autonomize, thus you’ll transform people’s impact. Do what you want as long as you have a strong focus on continuous improvement linked to your authorization to fail, to your understanding that good practices emerge in this changing world. Do what you want as long as you have true feedback a true look on finished things making sense, not on the number of features you’ve deployed, not on the number of hours you’ve spent, but on the number of additional users, on the number of phone calls to the hotline linked to your last delivery, etc. Often external and not internal measures. Thus if you’re able to prioritize these small autonomous elements making sense and carrying value you’ll know how to read, learn, bounce back on your market at lower cost and quickly reaping benefits. That’s the promise of agile.

You don’t have a time and money problem. You have an impact problem of your collaborators who aren’t sufficiently empowered, who don’t have enough autonomy, and you have a problem to maximize value: you’re not in a position to react, to learn vis-à-vis the market.

Everywhere invocations are flourishing: be happy, be motivated, be involved, be responsible, be happy, happiness chef blabla. But this can’t be decreed. Concerning engagement, concerning involvement, it’s not an injunction to which one can respond. You won’t be able to decide to make such and such person motivated. But you can create a framework, a context, that allow these people to be motivated, involved. We regularly see this message return: a very small part of employees in the world feel involved.

In the manifesto agile there’s a principle where it’s written: do projects with motivated people. Generally we laugh at this moment. Naturally projects work with motivated people. What an idea! Well then forget everything else, focus on the idea of engaging the people you work with.

Some explain that between an engaged person and an unengaged person the difference is enormous. In the Mythical Man Month the author (Fred Brooks) expresses the idea that a person (in his case, a computer developer) has a productivity ratio of one to ten depending on context. Their capacity would thus fluctuate from one to ten depending on context. My observations -on myself and others- tend to confirm this information. And I think the large part of this gap comes from the person’s involvement. Observe yourself performing a task on which you don’t feel involved, and one on which you feel involved, which you’ve appropriated. Personally I go from disheartened nonchalant poorly inspired to frenzied bulldozer highly productive.

We can’t decree motivation, nor involvement, nor appropriation. Yet there’s a domain, subject of study, where we discover involved, engaged people. With a high level of demand. When something fails, they try other ways, don’t let themselves be discouraged, they like to seek alternatives. Even the most introverted among them call friends for help or go read the documentation. Because – must it be mentioned? – online documentation is plentiful: “newbie” guides, videos, accompaniments, wikis, forums. But what is this domain? The people I’m mentioning spend several hours per week there, even several dozen hours, and, cherry on the cake, they pay for it…

It’s video games, and rather video game players. Why then this involvement in this domain? It’s exactly what we’re looking for in our organizations. All these online game players who pay to fail, restart, learn, redo, provide quality documentation, couldn’t we have the same engagement in business? The video game industry is flourishing, understand that it involves enormous sums of money. Before then for us to draw lessons from it for organization, it questioned itself, because its success is linked to the involvement it will generate. The observations that flowed from this research are a goldmine for us. To see: Jane McGonigal and to read: Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World by the same person.

But as I mention this subject, I receive my eldest son Mathieu’s school report. Mathieu has good academic results, but the report indicates that if Mathieu were involved he would have very good academic results. I look for Mathieu:

- Mathieu? Mathieu?

- (from the other room) Yes dad?

- Can you come so we can talk about your school report.

- Wait, right now I can’t, I’m building the fourth tower of my castle in Minecraft and it doesn’t have exactly the same decorations as the others, nor the same iron constitution, I can’t leave it like this.

- Yes that’s exactly what I want to talk to you about…

In other words Mathieu is very involved in his game, and his results are very good. What is the school missing to harvest this same engagement? What are organizations missing to have this same type of involvement?

It’s already not competition or the desire to win that will make this difference. I don’t believe we really win at Tetris or Candy Crush Saga, nor really at any of my son’s online games, he loses as much as he wins, that’s not his real quest. What we need and what these studies on video games teach us is desperately simple to state, but devilishly difficult to implement.

A Clear Objective

First a game that engages has a clear objective. Have fun testing if your project, your product, your organization has a clear objective. Easily statable. Think back to that famous quote from Einstein: “if you can’t explain it to an eight-year-old, you don’t know what you want”. Your job as leaders, as managers, is this clarification.

Clear Rules

I can’t cast a spell if I no longer have mana points, I can’t combine the power of these two weapons, but hey I could use houses to protect my tower and not the other way around. To take this space that will make all the difference, it’s appropriate to clarify the target, the objective, but also to delimit the framework in which one can flourish, surprise, imagine, appropriate. You must clarify the rules of the game. Naturally if your rules are too constraining the space you’ll propose will be weak.

Feedback, A Return Look

If I kill this monster I get 100 points, if I take this city I gain 10000 crowns, oh darn there was nothing in this dungeon. In the game we constantly know the benefits (substantial or catastrophic) that our actions bring. In the organization it should be the same. I delivered this feature, but it received no favorable reception, whereas the other yes, but not in the expected way. Yes this action was received positively, that one no, this one triggered that, the other that. No matter the result of your activity, you should measure it and know it, make it known. Without that your involvement will diminish. What’s the point of working if we don’t know what becomes of the fruit of our labor. The first step toward meaning is this feedback.

Invitation

More difficult. None of the video game players is obliged to play. Ideally none of the organization’s members should be obliged to come get involved, work. Not easy. We run into another reality, that of Maslow’s pyramid, one must first have a roof, eat, in short… have an organization and a salary before thinking about engagement. It’s a vast debate. But difficult today to invite to work, in any case not simple depending on contexts. So how to use the notion of invitation?

Let’s take some examples. Jim McCarthy, the very one of the core protocols was leading Microsoft Studio at the time. Facing all his teams he tried invitation: here are 15 projects*[1]*, “propose the teams you want so the projects are successes”. Turmoil among managers. People will do anything. But no. We’re living systems insists Harrison Owen (the inventor of openspace), we’re naturally responsible. It’s by disempowering people that you sometimes get completely absurd behaviors. In this framework and following the clearly stated objective: “that the projects be successes” people intelligently mixed socialization (group dynamics, friends) and skills. But especially crucial effect of invitation – of transparency on the reality of things: nobody will volunteer on certain projects. If there are two “stinking” projects, they’ll find themselves with nobody. That’s very good news. We discover there are complicated subjects in a blatant way, perhaps with surprise. Not that these projects shouldn’t be done, but it becomes clear they need to be given other means.

Another example, inspired by Dan Mezick, use invitation in your meetings. Imagine the big boss who proposes a meeting really on invitation. This big boss, we’ll call him Mesmaeker (Gaston Lagaffe…), invites twelve people. First option: nobody shows up. And that’s good news, because it was really a useless meeting. Everyone saved time. Second option: nobody shows up yet it was a useful meeting. The learning is clear for Mr Mesmaeker, he must rework his communication to make people understand the importance, the stake of this meeting. There, manifestly, his communication is ineffective. Third option: nobody shows up yet it was a useful meeting, and its importance was understood. But perhaps the priority wasn’t clear. Important things we all have to do. Mr Mesmaeker should have specified: and “it’s a priority”, or “it’s more important than…”. Still a question, communication problem made visible by invitation. Fourth option: four people show up out of twelve. They’re the four “right people”, because they’re the ones who understood the importance, who are ready to invest, who prioritized the importance in a way to put this subject forward (those who have time). Fifth option: the one you all know, it’s not a real invitation, the twelve people are there. They say yes “as is proper”. But we don’t know which ones have time, understood the importance, integrated the right priority, we don’t make necessary effort on the meeting format since everyone is constrained to it. And everyone says yes, but we don’t really know what that means.

You’ve understood invitation is key for engagement (and thus change management). But for our organizations it’s especially also a formidable transparency tool.

Invitation is also one of the pillars of the open agile adoption or openspace agility approach. The idea is to invite everyone to an open forum cyclically, an open forum that has an objective and framework (well well), to invite everyone to give the how of implementation. We thus obtain something very engaging and very respectful of people and organizations. I refer you to openspace agility/open agile adoption: here

Thus again, you don’t have a time and money problem. You have a question of involvement and engagement. And under these fairly simple precepts: clear objective, clear rules, feedback and invitation, hides a spectacular lever. But for leaders, managers, leaders, it’s constant work to clarify, support, evolve, accompany these clear objectives, these clear rules, this feedback and this invitation.

When Dan Mezick spoke to me about these ideas on engagement inspired by the world of video game players, in 2013, he often followed by also citing teachings from Tony Hsieh the leader of Zappos (when Zappos was a symbol of success). These four other elements I’m going to give you complemented, reinforced the previous points (being engaged - part 1). It’s with the years that I really understood this second list balanced the first as much: safeguard, resonance.

Here are the four points in resonance with those mentioned previously. To be involved, engaged, you need:

A Sense of Control

It’s the safeguard of the clear rules mentioned in the first series on engagement (being engaged - part 1). In that one I spoke to you about a framework, linked to a clear objective, and clear rules that helped take space, get involved, engage. They involve on condition they don’t hinder autonomy too much. They’re there to give autonomy, not constrain it. It’s about a sense of control of one’s work tool, not control of the other. Imagine an individual in a group starting their activity and who must ask another group for access to resources, machines, another group for the security right, production deployment, access to certain data… who can’t truly manipulate their work tool, because their jurisdiction is fragmented. No sense of control of one’s work tool, loss of involvement. That’s why often in an agile world we seek “feature teams”, multidisciplinary teams, they possess a capacity for autonomy, they control their perimeter. People must be able to appropriate their perimeter. Clear rules, but that preserve autonomy.

A Sense of Progress

There it’s simply the echo of the feedback idea I mentioned previously. To arouse engagement we should regularly know what we produce, generate, obtain. We should (very) regularly measure. For that we should (very) regularly finish things. And thus through this need for sense of progress I’d like to sensitize people not to work on too many elements at once. Multitasking is very harmful to our productivity. See this diagram: with one task I’m normal, with two I’m better, because I can switch from one to the other during incompressible delays. With three my productivity is already generally below that which I have treating one task at a time. If I move to four or five it becomes a disaster.

I come to tell organizations: “stop working on ten projects at once, focus on the three most important”. Sometimes they answer me, slyly, “but Pablo it was 8,9,10 that allowed paying you”. So I resume (heh heh): “stop the seventh you’ll finish it faster”. It’s a coherent global approach: if you know how to cut your projects/products into small pieces, you’ll know how to deliver substantial marrow in a shorter time span, and move on to the next. You start the next one later, but with a much stronger focus, and also this ability to condense value in a more reduced scope. And so on.

To be engaged, you must keep a sense of progress, nourished by feedback, you must know how to be focused on a reduced number of activities.

Belonging to a Community

With invitation we enter a group, a family, a team. It’s a welcome. Belonging to a community seems obvious to feel engaged, involved. It is, obvious. I take this opportunity to come back to what makes a group, a team, on some important figures. These figures I mentioned in the agile horde, in 2013.

Dunbar’s Number

Dunbar is a sociologist/anthropologist, he notes that prehistoric villages split around 150/220 people, suggesting that our physiology forbids us to have more than 150/220 real social connections. So if I want to encourage a sense of belonging to a community I’ll limit my “divisions, departments, agencies” to 150/220 people.

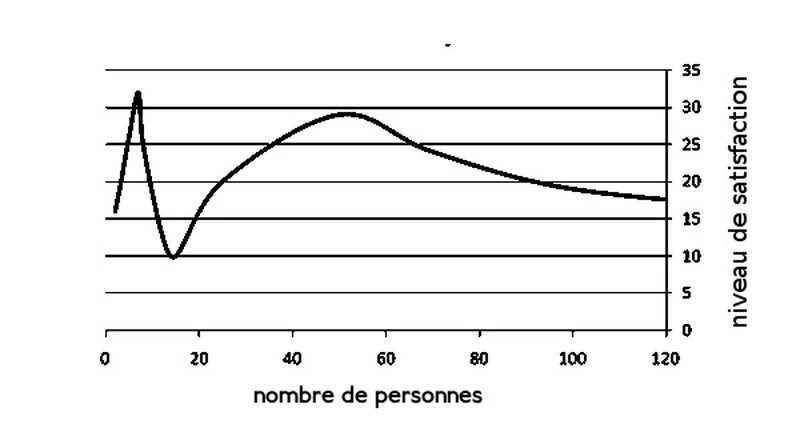

Pleasure of Belonging to a Group

With Christopher Allen’s research, we mention the pleasure of belonging to a group, what number triggers this satisfaction? The adjacent table indicates that the best feeling of satisfaction, which will support a sense of belonging, is felt around 7 and 50. So if I’m a leader, I’ll cut my organization into divisions of 150/220, then into departments of 50, then into teams of 7.

Often that’s when someone says we thus can’t do “big projects”, “large products” with a team of 7 for lack of capacity. Maybe, but with 7 teams of 7 we can. Naturally “big projects” bring a need for synchronization (that’s the whole issue of agile at scale, culture and synchronization), but it’s much easier to synchronize 7 teams of 7, than to work “rake-style” with 50 people.

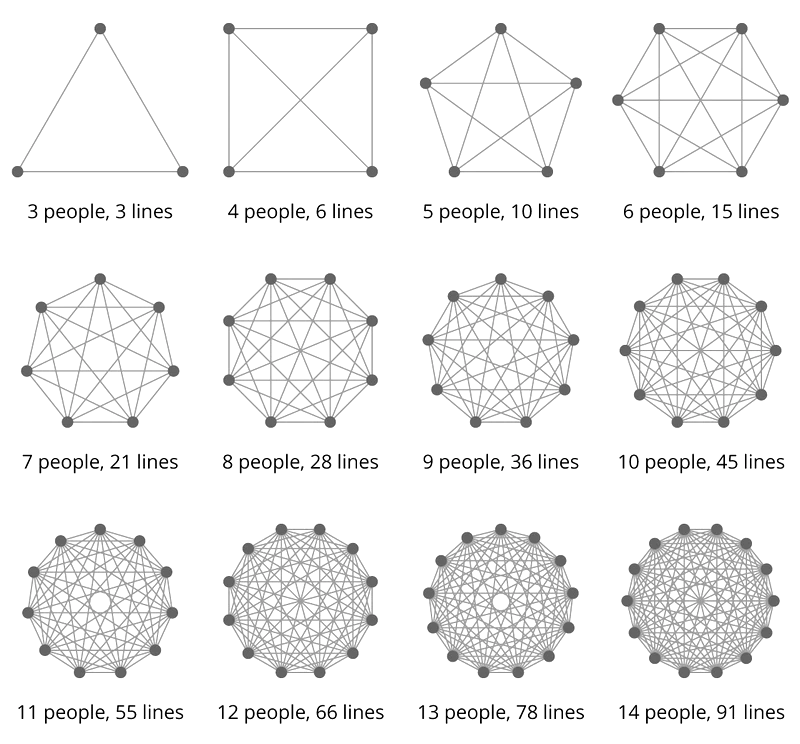

Interactive Communications

Finally the number 7 is corroborated by Fred Brooks’ observation (in the old and famous “mythical man month”), which visually demonstrates that the number of interactions becomes unsustainable as soon as we cross the bar of 7/9 people. That is, a real communication and team dynamic is built… from 4 (from four team sensation, with that it’s still individualities, it’s not negative however), up to 8. Beyond 8 we observe that interactive communications split into two groups.

Thus then in search of a sense of belonging I’ll decline my organization into groups of 150/220, then 50, finally teams of 4 to 8. Thus my involvement and my engagement will be better.

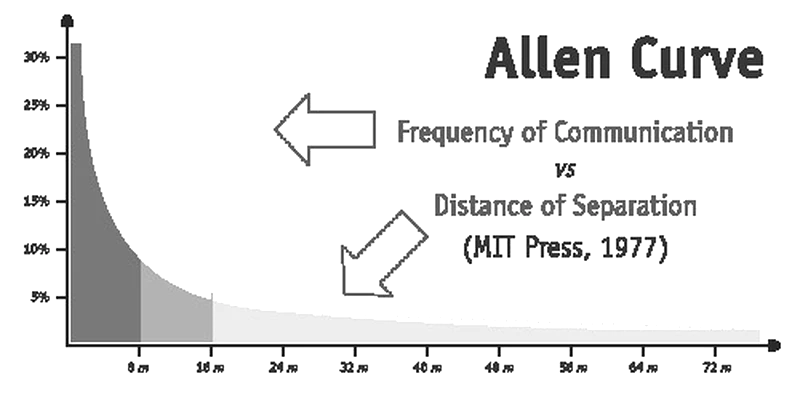

Allen Curve

Since we’re talking about communication quality, I often specify that co-location is key. This observation is reinforced by “official” studies (from IBM!) which describe that beyond 15m communication collapses. Aleister Cockburn uses the following metaphor: beyond the distance of a bus communication collapses.

These recent years I could question this question of distance and co-location, because technological innovations can make it invisible. Under the cover of several conditions, but that’s probably the subject of another article.

Working for Something That Exceeds Us, Greater Than Us

We spoke of a clear objective to engage video game players. In “real life” – as we often hear – it must be inhabited by meaning. It’s the fable of the stone cutter, I’m engaged if I’m not simply cutting a stone, or even if I’m not only doing that to feed my family, I’m engaged, involved, if I see the cathedral we’re building through my cutting.

Conclusion

I resume as I said in this series past writings, which still seem relevant to me with current and recent conversations. I’ll continue this reflection work.

To conclude on engagement: a clear objective that is inhabited by meaning, clear rules, but that leave enough space for autonomy and sense of control, feedback that allows a regular sense of progress, an invitation and the conditions for group dynamics.

-

I prefer mentor (“Attentive and wise guide, experienced advisor” says the Larousse) to coach (ambivalent and pretentious in my eyes, I don’t feel like changing you, neither the skill, nor the right, nor the desire). ↩︎